By Myles Ludwig

The current exhibit served up in the Esther B. O’Keeffe Gallery at the Society of Four Arts is an amuse-bouche, an appetizing slice of a much bigger and very personal pie that is a custardy view of American painting as seen through the eyes of the prominent collector and Wall Street eminence, Roy R. Neuberger

.

In his long life (107 years), Neuberger collected paintings, sculpture and artifacts that defined the idea of American Modernism in art. It is a very personal collection, and thus its title: When Modern Was Contemporary: Selections From The Roy R. Neuberger Collection. On view at the gallery is work that ranges from a brooding Morton Schamberg miniature to an imperious splash and drip of Jackson Pollock to a stark Ralston Crawford; a meditative Mark Rothko to a jokey chair by Alexander Calder and a rhythmic study of the square by Josef Albers that could qualify as a proto-Pantone’s color of the year and touches on all the movements of what is loosely called Modernism — or, out with the old and the bathwater as well.

The Pollock — Number 8, 1949 — is a layered abstract expressionist piece which covers the large canvas with sinewy splashes, splishes, drips and blots which could be parsed to find their beginning. Pollock generally painted with the canvas on the floor and did not try to control his movements; rather, he allowed them to follow his mood. His work was and still is controversial as its meaning is not clearly apparent, though he explained it simply as his childhood recollection of the Western night sky.

Crawford’s shapely At the Dock (1940) is from the dramatically graphic industrial landscape school and was also used as a cover for Fortune magazine. The Rothko, titled Old Gold Over White (1956), is typical of his work as a leading figure of the color field school and asks the viewer to contemplate the interplay of floating color, ghostly form and mood. Albers was concerned with reducing form to its essence, as were Seurat and Cézanne before him, and its title, Homage to the Square: Ritardando II (1958), suggests the musical form that slows the rhythm. The Calder — The Red Ear (1957) — reduces the chair to its essence, that of a curvilinear seat.

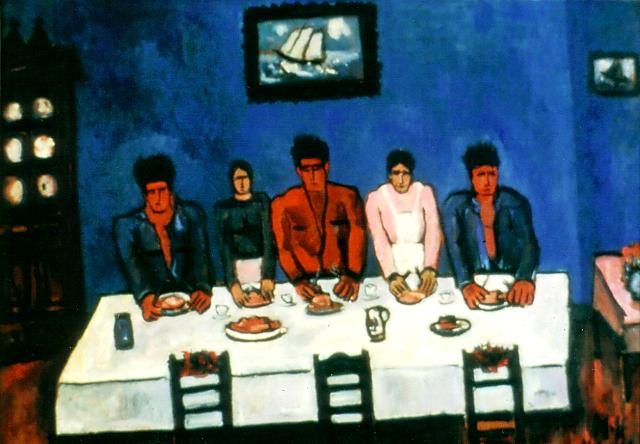

Marsden Hartley’s Fishermen’s Last Supper, Nova Scotia (1940-41), is a symbol-laden, cartoon-like painting of a family who lost their three sons at sea; thus the three empty chairs at the front edge of the piece to echo the absence of the three sons at the table and the painting of the sea-tossed boat on the wall behind them.

Congruent with the exhibit, Roger Ward, deputy director and chief curator of the Mississippi Museum of Art, presented an anecdotal travelogue of the artists, dealers and collectors of the New York art scene in the Neuberger era of the 1940s to early 1970s to a full house in the Walter S. Gubelmann Auditorium. It was a Chatty Kathy – and sometimes catty — tour of manners, foibles and peccadillos from Davis to De Kooning, Sam Koontz and “the den mother of Abstract Expressionism,” Betty Parson, to Sidney Janis. Though the prominent curator and art historian promised there would be no exam afterwards, I did wish his lecture could have been salted with more scholarship and less emphasis on what a bargain the work was when first acquired.

Neuberger’s motivation for collecting was, according to Ward, inspired by the story of the luckless van Gogh, who didn’t sell much, if any, work during his lifetime. Neuberger wanted to help support the younger artists of the day. He was a fussy collector, preferring the earlier and more conservative work of these painters such as Davis and Avery and buying only from dealers whose lifestyle he approved, thus cutting the grand dame Peggy Guggenheim out of his circle. He wanted work he thought would last and most did. His instincts were good. I like to buy used books for a similar reason; they have a history. As Susan Sontag wrote, “Collecting expresses a free-floating desire that attaches and re-attaches itself — it is a succession of desires. The true collector is in the grip not of what is collected but of collecting.”

(In the interests of full disclosure, I must say that I am a presenter of a workshop in memoir writing at the Four Arts’s Campus on the Lake and, therefore, this piece could conceivably be considered as a conflict of interest, according to my editor – from his lips to God’s ears.)

As to what constitutes Modernism, the very term is questionable depending on your perspective as an art historian, a sociologist, psychologist or philosopher. According to Aristotle (though I admit to being out of earshot when he said it), “It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it.” F. Scott Fitzgerald famously elaborated on that notion by writing, “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.”

In other words, mental multitasking.

Others have made similar remarks, but my favorite is supposedly an old Cherokee Indian proverb related to his grandson: “My son, there is a battle between two wolves inside us all. One is Evil. It is anger, jealousy, greed, resentment, inferiority, lies, and ego. The other is Good. It is joy, peace, love, hope, humility, kindness, empathy, & truth.” The boy thought about it, and asked, “Grandfather, which wolf wins?” The old man quietly replied, “The one you feed.”

Modern painting is painting that recognizes the surface of the piece as its reality, according to Ward, which is “the very definition of abstract,” as opposed to the mystical, quasi-religious, figurative, representational vanishing point painters of say, the Renaissance. But, by that token, cave art and Egyptian tomb paintings could be seen as ur-Modern.

Ward saw it as the painting of the 20th century, up to, say, Pop. The Encyclopedia Britannica notes “the roots of Modernism are often traced back to painter Édouard Manet, who, beginning in the 1860s, broke away from inherited notions of perspective, modeling, and subject matter.” My own starting point begins about 1908 in Vienna, when the unconscious as revealed by Freud became a fit subject for visualization.

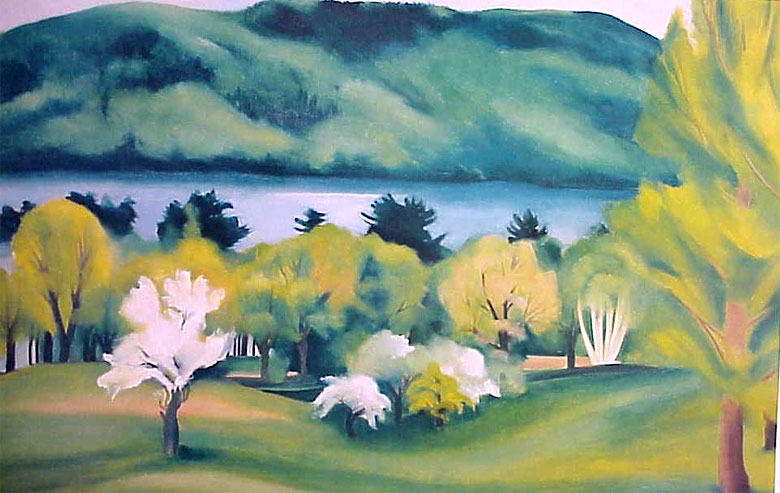

In any case, it is a pleasurable experience to view this outstanding collection. You will have an opportunity to peer into the painterly minds of Max Weber wielding a very Manet-like brush in an Ingres-manner to capture a typical odalisque, a lighthearted Marin beachscape and a pre-Bacon head in violent hues of red and green-blue by Stanton Macdonald-Wright, the founder of Synchronism.

However, a word of caution is necessary. The wiry barriers separating viewer for work are well-nigh invisible and I saw more than one patroness catching herself in mid-fall. Furthermore, considering the age of the gallerygoers and the size of the typography on wall captions, I overheard one say “I should have brought a flashlight” and another, “a magnifying glass.”

Perhaps these could be given out to attendees, like 3-D glasses at a multiplex.

When Modern Was Contemporary: Selections from the Roy R. Neuberger Collection is showing at the Society of the Four Arts, Palm Beach, until Jan. 29. The gallery is open from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Saturday, and 1 p.m. through 5 p.m. Sunday. Tickets are $5. Call 655-7226 or visit www.fourarts.org.