The best thing Sunlight Jr. has going for it is its setting. Laurie Collyer’s sophomore film was shot in Clearwater, one of the sprawling eyesores of metro Tampa, but it looks a lot of like certain stretches of Lake Worth, or Oakland Park, or North Miami, or hundreds of other depressed stretches of dollar stores, fast-food joints and scalding macadam, where the city meets the ghetto.

Collyer has a clear-eyed view of strip mall Americana, where construction projects signify more soon-to-be-shuttered budget stores, where pawnshops and check-cashing establishments straddle each other in sad little roadside formations, fluorescent and neon reminders of the permanent poor. As for nutrition, the gas station depot is the dispenser of a myriad variety of doughnuts, Big Gulps and suspiciously inexpensive hot dogs.

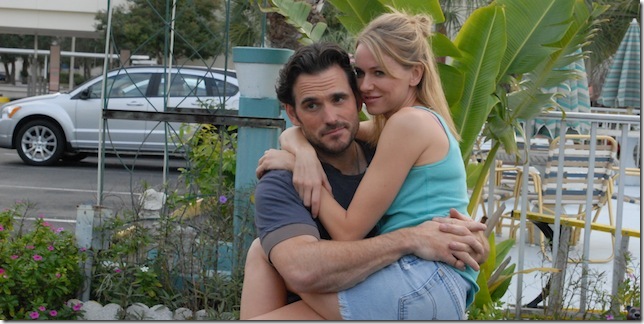

It’s in one of these establishments that our woebegone protagonist, Melissa (Naomi Watts), has found employment, a hellish filling station with the ironically cheerful name Sunlight Jr. She’s saddled with a repugnant assistant manager (Antoni Corone) who makes sexually harassing comments, and a drug-dealing ex-lover (Norman Reedus) who has resumed stalking her at work, thanks to a lapsed retraining order. The only plus in her life is her boyfriend Richie (Matt Dillon), a disabled former construction worker living off disability and grappling with alcohol addiction and anger issues. Yes, that’s her only plus. As her mother, a slice of white trash raising a flock of malnourished children, advises her, Richie is a keeper because “he doesn’t hit you.”

All of the men in Melissa’s life treat her like crap at one time or another, and she takes it all in, eventually accepting a graveyard shift at Sunlight Jr. despite her protests. She soon discovers she’s pregnant by Richie, but it’s only a matter of time before the naïve hope of salvation through a child disintegrates.

In the real world — the world of vagrants pushing shopping carts in front of thrift stores, of single parents nourishing children on food-stamp ramen, of penniless men siphoning gas from other cars to fill their tanks, all of which are rendered with wince-inducing accuracy under Collyer’s lens — people like Naomi Watts would rarely succumb to such hardship. Dillon is a convincingly shopworn, grizzled and bitter archetype of the forgotten man, but Watts looks and acts like a far more employable person than her Melissa is supposed to be.

That one casting decision aside, the main problem with Sunlight Jr. is its pointless miserablism. It’s a staple in Indiewood to wallow in suffering for suffering’s safe, to present a gaping rot but offer nothing in its narrative beyond that presentation. Hardscrabble realism can be just as lazy as melodramatic phoniness if there’s no there there, and there’s no there in Sunlight Jr. Even J. Mascis, the much revered alt-rock guitar god, seemed to realize this in his shockingly banal score, which manages to sound nondescript and intrusive at the same time.

Sunlight Jr. works when Collyer allows herself to break from the morose muck and exhibit a little poetry, like when Melissa suddenly sees her future self in a older woman desperately scratching off lottery tickets before paying for them — assuming she pays for them — and when Richie daydreams during an appointment at an employment agency, with his grand fantasy being simply the ability to walk out the front door.

In these moments, and in the way she presents life in Flint … er, Clearwater … Collyer captures an ambience of malaise as expertly as any director I can think of. But while location may be everything — and it’s certainly well-utilized here — there’s not enough enlightenment or originality to keep us invested in the people living among these ubiquitous symbols of urban decline.

SUNLIGHT JR. Director: Laurie Collyer; Cast: Naomi Watts, Matt Dillon, Norman Reedus, Antoni Corone; Distributor: Samuel Goldwyn; Rating: R; Opens: Friday at Living Room Theaters in Boca Raton, Cinema Paradiso in Fort Lauderdale and O Cinema in Miami Shores