Reading Sara Gruen’s Ape House, I was reminded of one April Fool’s Day when my daughters were 6 and 4.

I got up in the morning and excitedly called them: “Come quick, our cat Mittens is talking!”

Their astonished but not disbelieving faces as they rushed into the living room, expecting to hear our housecat opine for tuna rather than Meow Mix delighted me, and we all ended up laughing wistfully at the very idea.

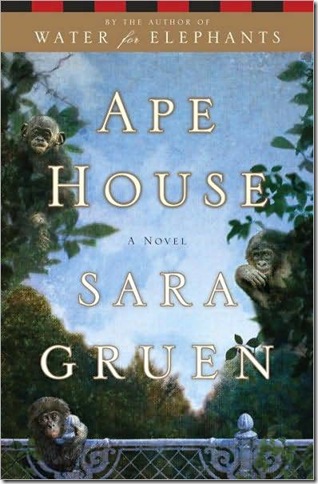

It’s that type of amazement and gratification regarding animals actually communicating with us in language that forms the premise of Ape House. Gruen’s first wildly popular best-seller, Water for Elephants, also centered on animals in captivity and their relationships with humans.

This time, she focuses on bonobos, small cousins to chimpanzees, and the theme is tantalizing to animal lovers everywhere: An animal that talks, and lets us in on the mystery of those simian, yet achingly human, eyes.

Gruen’s novel begins in the fictional Great Ape Learning Lab. Here, Dr. Isabel Duncan has been teaching bonobos American Sign Language. The six bonobos are immediately captivating, and individually rendered, from the matriarch Bonzi, to the adolescents, the alpha male and the baby Lola. Gruen says in her acknowledgements that she based much of the apes’ dialogue and actions on real events that happened when she visited and studied the Great Ape Trust in Des Moines, Iowa.

Unfortunately, while Gruen spins us along on a fast-paced plot involving a journalist, the scientist who loves the bonobos like her own family, and a nefarious reality show showcasing the apes that captivates the nation, she leaves behind the best part of her novel: the relationships and characters of the apes themselves.

In addition to the quickly but sweetly rendered bonobos, Gruen’s characters are John Thigpen, a newspaper reporter who begins a feature on the apes and then, when the lab is mysteriously bombed setting the apes free, finds it becoming the biggest story of his career; Isabel Duncan, the scientist who has devoted her life to them; and an ever-expanding crew including the lab director (who is Duncan’s fiancé) , Thigpen’s Hollywood-bound and biological clock-ticking wife, a porn filmmaker intent on using the bonobos to establish ratings, and a roster of others that push this novel to the bursting point.

Unlike Water for Elephants, which shifted time periods and had a historical quality, Ape House is thoroughly modern. The real time references and themes are promising at times: the bonobos become stars of the world’s most popular reality show, Ape House, which has millions glued to their sets watching the apes order in cheeseburgers, candy and pizza, have sex constantly, and skim board on the wet floors with ripped off cabinet doors.

But Gruen’s characters lack depth. She explains Isabel’s closeness with the apes with a conveniently horrible childhood rife with abandonment. We never understand why a woman who is so in tune with primates would be captivated by the increasingly suspicious Dr. Peter Benton. The plot twists often are not explained. Why does Benton put his uncharacteristically drunken fiancée in a cab on New Year’s Eve and stay behind, only, we learn later, to have sex with a flirty intern?

I was tantalized by the possible plot turns afforded by the evil Cat, the journalist colleague who pushes John Thigpen out of his enterprise story on the apes and takes over. Why does John’s editor let this happen, and where is his internal angst or rightful anger over this turn of events? Why does he slouch back to work on the Urban Warrior column with no argument, enduring evermore humiliating assignments?

But Gruen abandons her character portrayal in favor of a plotline that becomes a predictable thriller. Where the reader should have been worrying about whether Bonzi and the other apes would ever get back home, it becomes assumed this will be the happy ending because the story has become so clichéd, down to the rescued but lovable giant of a pit bull dog. Why was that bombed-out meth lab in the book, anyway?

Ape House is an enjoyable novel, but I expected it to evoke more emotion. If Gruen had stuck to exploring the apes’ characters and their relationships to each other and the humans, while also looking at the underlying questions of keeping primates in captivity, it would have been much more satisfying.

If I cried when I read a short article about Koko the talking gorilla and her relationship with the cat she named All Ball, certainly a whole novel about apes who also talk, who love, and who form bonds with their humans, could have caused at least a little sniffling.

Terri L. Parker is the investigative reporter for WPBF-Channel 25 in West Palm Beach. She was an English major at the University of Virginia.

Ape House, by Sara Gruen; 320 pp., Spiegel & Grau; $26.