Great opera stars have extended their careers for many years with lieder recitals, and they have a vast repertory of art song to choose from.

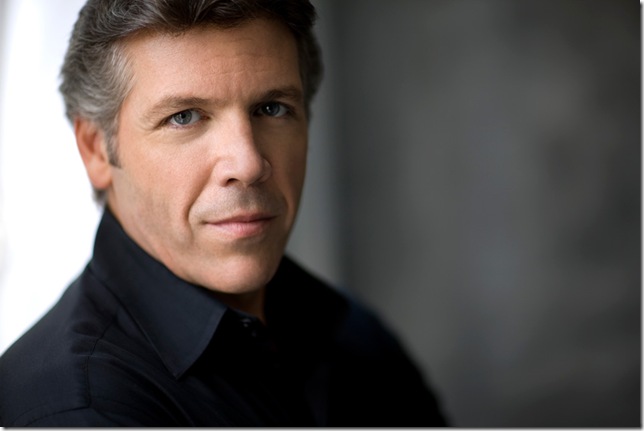

America’s baritone, Thomas Hampson, came to the Four Arts on Feb. 11 with a lieder recital. The debonair singer is surely one of our finest ambassadors. Still active operatically in 2015, Hampson will be singing on stage in New York, Paris, Vienna, Munich, San Francisco and Dresden this year, with song recitals in Milan, Amsterdam, Israel, Schleswig-Holstein, and Linz.

The last part of his program at the Four Arts held his “Song of America” project, which he originated and researched. The United States has a history in this art form beginning just before the Revolution with Francis Hopkinson (1737-1791), a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

Beginning with five lieder by Richard Strauss, Hampson’s voice was rich and strong. His “invisible” breath control and clever interpretation put mystery into “Heimliche Aufforderung. In “Freundliche Vision”, he was very tender and got across its subtle meaning easily. In “Mein Herz ist Stumm, mien Herz ist kalt,” Hampson dug deep to come up with a forceful even tone which displayed his rich baritone nicely. “Sehnsucht” was beautifully sung and reminded one of the great talent this artist brings to his work. “Ruhe, meine Seele” brought out his delicate delivery and a rapturous quieter sound. Warm applause greeted the singer and pianist Wolfram Rieger.

Apologizing to the audience Hampson noted that the house lights were so dark it was impossible to read the words in the program as he was singing. The lights immediately went up (every song that followed was in English!) He then spoke of a new set of songs he was about to sing by the celebrated American composer, Jennifer Higdon, who dedicated them to Hampson. She named her song cycle Civil Words, drawing on the 150th anniversary of our Civil War.

The first song, “Enlisted Today,” about a mother sending her son off to war, has an anonymous text and a very attractive tune, and the English sits nicely in Hampson’s register. To my ear there’s a smattering of Roger Quilter in Higdon’s lyrical quality and the Benjamin Britten-like silvery notes in the piano accompaniment infer his subtle influence too on Higdon’s compositions. The second song, “All Quiet,” words by Thaddeus Oliver, tells of a soldier’s death in march time. Next came “Lincoln’s Final,” about the hopes of the Union leader, written by his own hand. It’s majestic in structure and Hampson’s voice was extremely radiant here, appropriate because the piece and song are so moving. “The Death of Lincoln,” to words by William Cullen Bryant, is set to a melancholy mood with the pianist subduing the piano strings with his right hand while strumming a “death knell” with his left hand. An intrusive novelty to my mind, but the German pianist handled it tactfully.

Last came “Driving Home,” with a text by Kate Putman Osgood that relates to a great loss and sums up the universal effects of war. It begins in a romantic vein and slows to a regretful end. Hampson gave of his best work in these songs as dedicatee. And it must be said that Jennifer Higdon has the gift of matching words, syllables and vowels to notes with clean precision that I find quite appealing. So fresh off the press was Civil Words that Thomas Hampson had not committed them to memory, but read them as he sang. He’s such a pro it had no effect on his delivery; in fact, at times he was gently shaping words, moods and notes with his hands. His voice was wtrong and lyrical throughout this second song cycle.

After intermission, Hampson offered 10 songs from “Song of America.” The first, Hopkinson’s “My Days Have Been So Wondrous Free,” is very Handelian, and a delightful air from a man who helped design the American flag. Next, an old folk song, “The Dodger,” arranged by Aaron Copland, was used in the 1884 general election to deride candidate James Blaine who had a known history of corruption. It was a lot of fun, with plain verses and speeded-up riffs at the end of each verse in the form of a warning. Hampson tackled this one with glee.

A Charles Ives song, “Circus Band,” followed about a boy’s impressions when the traveling circus arrives in town. The words are Ives’ own, and Hampson, like the fine actor he is, got in character, becoming the excited boy. Switching to a serious stance to sing Col. John McCrae’s poem “In Flanders Fields,” set to music by Ives, Hampson gave it a strong interpretation. His voice was almost stentorian in this grim depiction of the dead, their red blood blending with the red poppies in the Flanders fields of Belgium during World War I.

“Song of the Deathless Voice,” also a memorial to a dead warrior, by Arthur Farwell, was next. It is based on an American Indian tune with enhanced harmonies by the composer. Opening very loudly with eerie ear-shattering Indian war cries, beautiful music takes over and from then on Hampson’s voice sounded lovely, especially as he delivered the last line, “Joy was in his voice as he passed over.”

Margaret Bondswrote the next song, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” to a poem by the 19-year-old Langston Hughes. A trailblazer among African-American women composers, Bonds’ work relied heavily on spirituals, and this song is no exception in its emotional warmth and descriptive music. There is a piano interlude halfway through, which is near-brilliant in its composition. On the word “sunset,” pianist Reiger played Bonds’s beautiful music with loving care at the end.

The well-known condolence letter from Abraham Lincoln to Mrs. Bixby (whose five sons were thought erroneously to have died in battle) was made into a song by Michael Daugherty who took it from an old Anglican hymn, “O Sacred Head, Sore Wounded.” That was followed by Elinor Remick Warren’s “God Be in my Heart,” an overly sentimental setting of some 16th-century words. Frankly, it was the one song I did not care for in this recital.

Hampson ended his program fusing two songs together, “Shenandoah” and “The Boatmens’ Dance.” Both traditional American folk songs, in “Shenandoah” his operatic voice took over to great effect. Arranged by Stephen White, it’s a song about pining for a sweetheart and the land left behind by young men migrating west. “The Boatmens’ Dance,” arranged by Copland, is indeed a boisterous song about life on the Ohio River that starts slowly with each verse ending in a quick rebuke.

Hampson got his tongue around some twangy accents here and beamed at his audience as they tried for an encore. No such luck; he knew to let them go away asking for more.