In its first program of the season, Fire and Ice, Miami City Ballet brought the work of three very different choreographers to bear, and with surprising results.

The “ice” part of the program was Sir Frederick Ashton’s Les Patineurs, a light-hearted winter wonderland of skaters on a frozen pond that was reminiscent of a Hallmark Christmas card. Les Patineurs, set to music by Giacomo Meyerbeer, was first performed in 1937 at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre in London with a cast that included Margot Fonteyn. This plotless and accessible ballet was such an instant success that it was performed every year for the next 30 years.

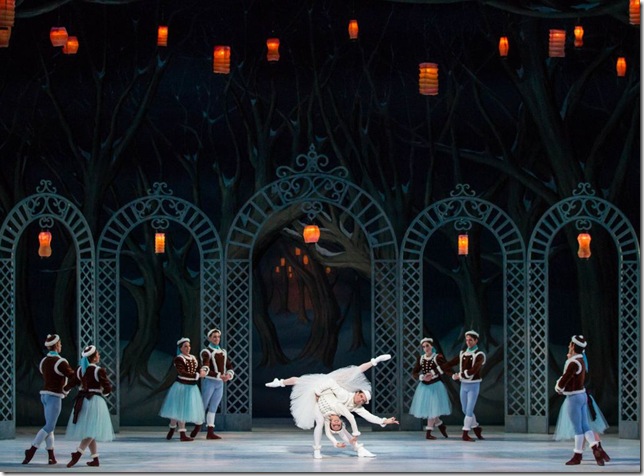

Filled with the charming silliness of young skaters’ antics, the choreography utilized lovely upper-body movement in contrast to fast footwork. The marvelous scenic design of lanterns hung from a canopy of enormous trees with a latticework of arches that surrounded the white ice of the pond, reminiscent of a cut-out, pop-up children’s storybook. Both the set and costumes were from the original designs of William Chappell.

Nathalia Arja and Jennifer Lauren were quick-footed and delightful as The Girls in Blue. Mary Carmen Catoya was lovely and fluid in her dancing with partner Reyneris Reyes. Renato Penteado was the charming daredevil skater who did multiple quick and clean beats and turned and turned and turned until the curtain came down. Les Patineurs was an enjoyable piece of ballet history, well-danced by the company, and it warmed up the audience.

Though Frederick Ashton and George Balanchine were contemporaries, their choreographic styles have little in common. In fact, the two works on the MCB program couldn’t have been more of a contrast. Though choreographed nine years earlier than Ashton’s Les Patineurs, Balanchine’s Apollo is decidedly more contemporary and is regarded as Balanchine’s first great work. It is also the first work on which he collaborated with composer Igor Stravinsky, with whom he later worked extensively.

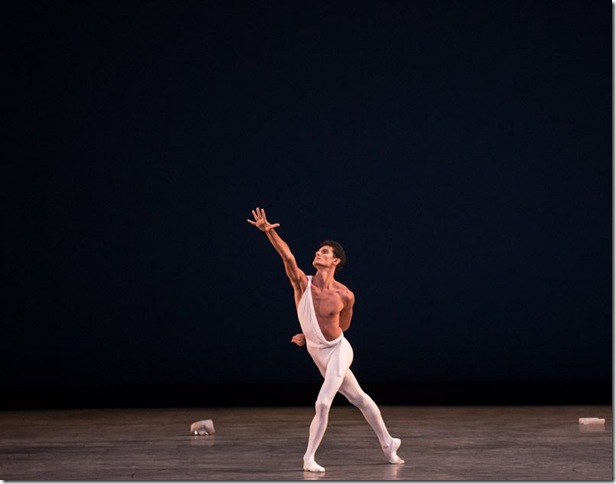

Everything about the work is abstraction and minimalism. Inspired by the music, which has a calmness and clarity, the stage was open and bare, the costumes were white and simple, and the movement was clean and architectural. Here, Balanchine achieved a union of his Russian ballet background with a style of sparseness that paved the way to the neoclassicism that became the hallmark of the New York City Ballet, the company he founded and directed for more than 40 years.

The dance draws upon ancient mythology and the story of Apollo, the god of music, who is visited by the Muses of dance, poetry and mime. Apollo, a coveted role for every male dancer, was performed by long-limbed Renan Cerdeiro. Patricia Delgado, Tricia Albertson and Jeanette Delgado were the Muses who danced in and out of interwoven arms with him. Later, each danced alone for him.

In the program, there were very extensive notes explaining the interaction of the roles of the characters, but the dancers onstage kept the acting quite matter-of-fact, even in the supposedly romantic and tender duet between Apollo and Terpsichore, the Muse of the dance, Patricia Delgado.

Piazzolla Caldera, the last work on the evening’s program, is choreographed by one of the greatest modern dance icons, Paul Taylor. Set mostly to the music of Astor Piazzolla, it was a view of the dark and vibrant dance halls of Argentina where the tango was conceived. A sultry and somewhat sordid world of people passing and merging in liaisons of the late night, it is far from the vision of Ashton’s Victorian skaters and Balanchine’s god and Muses.

The stunning choreography and vivid lighting were surely the intended “fire” part of the program; however, Friday evening’s performance of this work was more fizzle than sizzle. Ragged formations and unison work, as well as lack of intensity and interaction of focus between the dancers, took the tango out of the tango: Every arm movement should have had the desire of an embrace in it.

Interestingly, Taylor actually never used an authentic tango step in Piazzolla Caldera even though the choreography oozed it. The weighted dynamics and electric use of the body’s core necessary both in the tango and in Taylor’s trademark movement style is often elusive to ballet dancers and to their intrinsic movement quality.

As it turned out, the Fire (Piazzolla Caldera) on the program was a little too cool, but the Ice (Les Patineurs) was pretty hot.

Miami City Ballet repeats the Fire and Ice Program today at 2 p.m. and 8 p.m., and at 1 p.m. Sunday at the Kravis Center. Call 561-832-7469 or visit www.kravis.org.