Gone is the perfectly white snow. Instead, a tint of light green, pink, violet and blue break up the monotonous purity. Sloppy features, cutoff figures and messy sceneries replace the refined finish and safe realism.

Impressionism entered the French scene in the 1870s and got everyone obsessed with light and color. Before it, you could say painting was like a controlled experiment. It took place in a safe environment (the studio) with the elements (lighting, subject, shadows) prepared beforehand as to leave no room for surprises.

The Society of the Four Arts is dedicating the next two months to the movement that freed painters from the laboratory-like experience. The striking exhibit titled Painting the Beautiful: The Pennsylvania Impressionist Landscape Tradition features more than 50 works by Pennsylvania-based artists who adopted this French style of painting and agreed that feeling nature was the best way to capture its essence. The group includes works by Antonio Martino, Walter Schofield, Morgan Colt, Arthur Meltzer and William Lathrop.

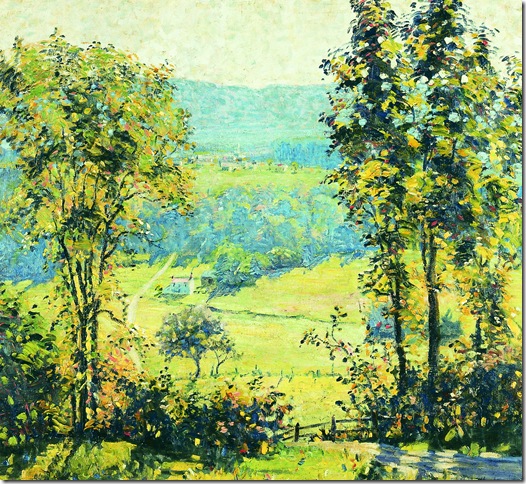

Also known as the New Hope School, these artists found special interest in the trees, hills and the picturesque vistas and villages of a sleepy rural community along the banks of the Delaware River. Their names are not as recognizable as Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas or Claude Monet, but they took painting as seriously; often spending long hours outdoors under severe weather conditions. A lot was at stake.

Aside from agriculture, Bucks County, Pa., in 1898 had very limited industry, which meant the artists did not have a lot of options to make a living. When their paintings would not sell, they would go fishing or do gardening to get by. Others would trade works for goods and services. Edward Redfield, one of the main figures fueling the movement from the beginning (along with Lathrop), would strap his canvases to trees in windy days. Fern I. Coppedge, another artist, wore earmuffs and a thick bearskin coat to paint her vivid winter scenes.

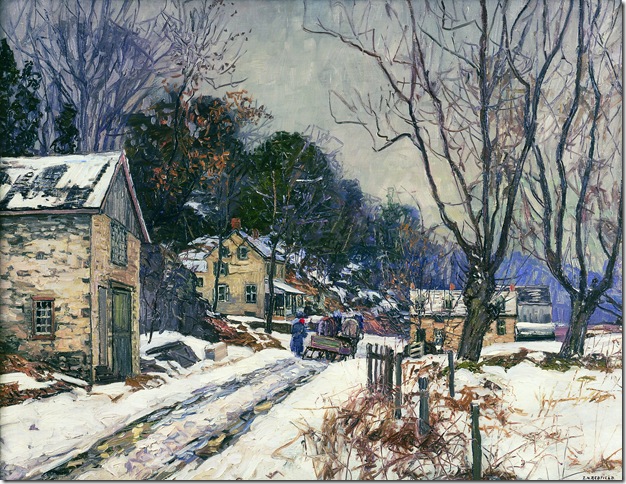

In the words of Coppedge: “I have to be cold in order to paint it to look cold.” Her The Road to Lumberville (aka The Edge of the Village) is a square piece that manages to make us feel chilly despite featuring colorful houses. The road covered in snow is slightly blue, green and pink as if the colors of the homes had melted and contaminated the white space. In a show filled with subdued moody landscapes, Coppedge’s stands out because of the darker tones and contrast.

Canal at Lumberville by Fred Wagner is a gloomy picture of reality. Snow covers the roof of wooden little houses and there is nobody in sight. An old wooden boat sports a worn dirty orange hue as if to emphasize the severity of the moment. A line of hard stripped trees adds a chilling effect to the already depressing picture.

By contrast, Cheerful Barge 269, by M. Elizabeth Price, depicts a bright orange barge sliding by the canal waters on a sunny day. The water appears covered by leafs but it is only the reflection of the trees. Stones create a little path leading the way toward the viewer while a very tall red flower grows on the bottom right corner of the frame as a last-minute thought. It is not a picture of perfection. It does not get everything right down to the last detail. And yet, the essence of the moment is captured. It feels more real, dynamic, instead of perfectly frozen in time like a fake smile on a photo. Cheerful Barge is instead like that blurry photo we keep because we love its uncertainty.

Before Impressionism, composing landscapes in a studio was the norm. Impressionists believed in order to be faithful to nature it was necessary to paint en plein air (in the open air). This meant they had to work quickly and constantly adjust to the changes in light and conditions. They delivered harsh brushstrokes and avoided firm lines for the most part. Their colors often appear fusing and take turns at being another color’s shadow.

But even this general approach was broken from time to time. The impressionist works out of Bucks County were not all the same. Change and variety emerged as soon as the artists stopped merely capturing the landscapes they saw and began interpreting and meditating about them.

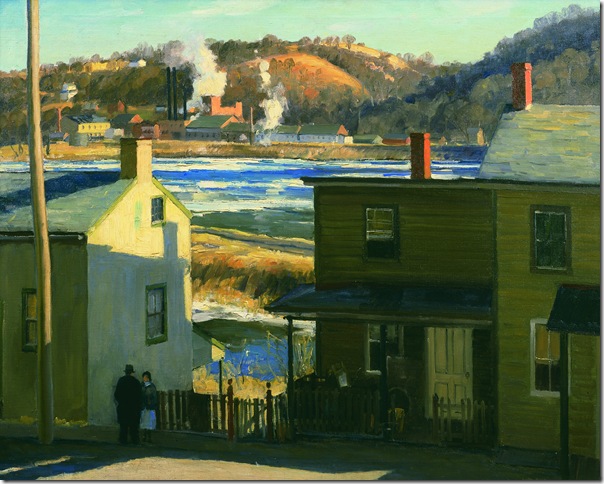

“I believe in nature to the extent that I get my inspiration to create from nature,” said John Folinsbee, whose earlier works differ tremendously from his later pieces. A limited palette of lighter colors and thicker brushstrokes are spotted in Folinsbee’s Corn Shocks in Winter from 1922. This was in part due to Redfield’s influence on the artist. But that changes in 1936 with Bowman’s Hill, where the brushstrokes are less gestural and the colors more varied and darker. The end result is a lot cleaner and more dramatic than most pieces on display.

Some artists used lighter, pale colors while others such as Folinsbee preferred darker tones and contrast. Some focused on the natural scene while others gave preference to human figures and buildings.

Concrete Bridge by Robert Spencer gives us a glimpse of a massive structure that gets lost in the foliage and vegetation of the place. At its base, a woman is seen feeding chickens. A similar marriage of structure and man is seen in his The White Mill and The Upper City where buildings appear larger, closer, no longer tiny shapes in the distance.

“It’s the human side that interests me … a landscape without a building or a figure is a very lonely picture to me,” Spencer once said.

Impressionist works are always special, like a delayed reward. Objects can look out of place, messy and even blurry, especially if you stand too close to them. Structures do not seem firmed, leafs appear floating in the air instead of attached to branches and shadows are colorful instead of gray. But stand from a distance and all the colors and lines that made little sense before, form a visual harmony that delivers that cold winter scene or sweet summer landscape. It is not about noticing every single imperfection but taking all the imperfections in at once and watching them become invisible.

As other impressionist painters, the Bucks County artists were not guided by a universal notion of beauty. What we are looking at in Painting the Beautiful is their impressions of what they believed to be beautiful: snow, trees, a broken fence or a dirt road. In that sense, it is a highly personal show coming from artists concerned not so much with fitting under the “ism” of impressionism but with developing their own voice.

Painting the Beautiful runs through Jan. 20 at the Esther O’Keeffe Gallery at the Society of the Four Arts, Palm Beach. Gallery hours are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Saturday, and from 2 p.m. to 5 p.m. Sunday. Admission is $5; free for members and children 14 and under. Call 655-7226 for more information.