Two adjacent exhibits, now on view at The Society of the Four Arts in Palm Beach until Jan. 15, demonstrate why illustration should be given due consideration within the context of the history of art in America.

Yet also, as the complement to the journalism of their day, the works on view provide a visual thumbprint for our nation’s ideology during different times in our not-too-distant history, as well as demonstrate how rapidly this collective mindset has changed.

The Art of Illustration: Original Works of Howard Chandler Christy and J.C. Leyendecker and Andy Warhol: The Bazaar Years 1951-1964 are two shows that have been made possible by the Hearst Corp. Publisher William Randolph Hearst believed that illustration was an important tool for successful journalism. He hired the most talented illustrators. He invested in color printing technology as soon as it became available and he fully understood the power of imagery to elicit the reader’s imagination.

Illustrator Howard Chandler Christy was born in Ohio in 1873 and was actually a descendant of Capt. Myles Standish. He moved to New York when he was in his early twenties so that he could study at the Art Students League under the tutelage of the American Impressionist painter William Merritt Chase.

By 1895, he’d embarked on a career as a magazine illustrator, even doing many of the drawings of Theodore Roosevelt and the “the Rough Riders” during the Spanish-American War. By 1910 he was working primarily for Hearst, and mostly for Cosmopolitan, where he stayed until 1921.

Christy’s work shows the romanticism of the age in which he lived, which glorified the horrors of war by proffering heroes. Most of his work in this exhibit centers on soldiers. They are sturdy idealized figures. Christy is also known for creating the “Christy Girl,” illustrations of beautiful women that are also emblematic of their time, and often compared to the “Gibson Girl.” In works such as American Colonial Woman Watching Over a Wounded Man (Note: the titles used here are descriptions, as these works are untitled), we see one such beautiful woman depicted as an angelic caretaker.

Christy’s works were done in the early 1900s, yet their subject matter is the decade prior. Leyendecker’s work is mostly from the 1940s, a mere 30 years later, but we see a significant shift in how the American attitude towards war has changed. Men are still heroic, but romanticism has been replaced by a pragmatic optimism — one that acknowledges the sacrifices of war, as shown in Leyendecker’s Memorial Day.

Joseph Christian Leyendecker, who went by “J.C.”, was actually born in Germany but emigrated to the U.S. when he was eight. He returned to Europe to study at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, but then shortly after moved to New York and almost immediately became a successful illustrator. It’s very easy to see how his work influenced another great illustrator.

“Leyendecker influenced Norman Rockwell, who adored him,” said Nancy Mato, executive vice president and curator. Indeed Rockwell spoke in his autobiography about how he studied Leyendecker’s technique. But while Leyendecker also did many covers for The Saturday Evening Post, the ones on view here are from Hearst’s publication, The American Weekly.

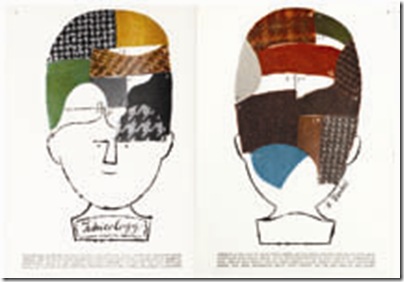

Everyone knows who Andy Warhol is, but many people don’t know that this iconic leader of the Pop Art movement was first a successful illustrator. Between 1951 and 1964 he created hundreds of illustrations for Hearst’s Harper’s Bazaar. Warhol began working as an illustrator shortly after he arrived in New York in 1949 after graduating from the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh.

A delightful selection of the works Warhol created are on view here and even the most die-hard Warhol fan may not have seen some of them. The opportunity to see them shouldn’t be missed. Mato admits to accepting the works, sight unseen, as soon as Hearst called to offer them to Four Arts.

“I was excited when I heard. I didn’t know what they looked like, but I knew this would work with our audience. I was so delighted when they arrived,” she said.

Rightfully so, as these works reveal a side of Warhol that few would associate with the bizarre, angst-ridden, white-haired weirdo portrayed in films such as Basquiat and The Doors. This Warhol has a notable sense of humor as well as a sense of whimsy, aptly demonstrated in an illustration that accompanies a narrative called “Making Less of Oneself,” which extols the virtues of self-control, and throughout all of the works displayed, which are colorful and lighthearted.

If Christy’s work demonstrates bold romanticism, and Leyendecker’s work pragmatic optimism, then Warhol’s work heralds the origins of our nation’s obsessive consumerism and preoccupation with image, particularly the image of wealth, beauty and affluence. Here, the focus is not war, but fashion. As such, the images have no great depth, but they’re remarkably fun and are sure to bring a smile to anyone’s face. What you’ll see are shoes, purses, lipstick cases – all the accoutrements of fashion.

However, exactly what makes these two exhibits so impactful is that they’re presented simultaneously. While each could successfully stand on its own, shown together they present the viewer with the visual story of how Americans have viewed themselves over an almost 100-year period of time.

The progression from military boots and bayonets to purses and perfume certainly provides ample material for the contemplation of a profound shift in our national identity, and values, over the past century.

Jenifer Mangione Vogt is a marketing communications professional and resident of Boca Raton. Visit her blog at http://www.fineartnotebook.com.

The Art of Illustration: Original Works of Howard Chandler Christy and J.C. Leyendecker, and Andy Warhol: The Bazaar Years 1951-1964, are on view at The Society of the Four Arts until Jan. 15. Hours for this exhibition are Monday through Saturday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., and Sunday from 2 p.m. to 5 p.m. Admission is $5. For more information call 561-655-7226, or visit www.fourarts.org.