More than 60 artworks by nonconformist Kyiv artists freed from Soviet influence speak to the fearless spirit of a nation still fighting for its way of life. Once unleashed, their long-suppressed individuality led to a wave of creativity that took the region by storm.

The traveling exhibition Painting in Excess: Kyiv’s Art Revival, 1985-1993, showing at Coral Gables Museum through Dec. 11 presents the voracious artistic manifestations emerging out of the quiet province with the fall of the Soviet Union, subsequent economic collapse, and the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster. The selection consists of bold Ukrainian works — striking in color and scale — produced during the period of perestroika (restructuring) and pick up where the prior avant-garde wave from the 1960s and 1970s ended. Many of the works on view can no longer return to the country because of the ongoing war.

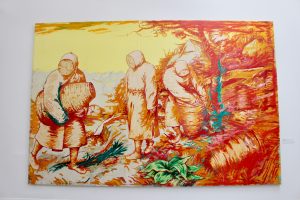

A prime example of the innovative styles advanced by Ukrainian artists during this transitional period that welcomed exploration and diversity of thought is Georgii Senchenko’s Sacred Landscape of Pieter Bruegel. The wall-sized oil piece inspired by the Flemish artist’s rendition amplifies the dramatic effect via complementary bright colors in yellows, oranges and reds. Three beekeepers bearing flattened masks resembling tree stumps do not seem to share the sense of urgency an impending mushroom cloud would typically elicit.

There’s a vague attempt at fleeing by the character on the left while the center figure exudes the stoicism of a monk. Perestroika art was characterized by figurative imagery and large vigorous canvases such as this piece from 1988. It is the first to pierce us upon entering the show and lingers on long after we leave it.

The enduring power of color is exploited by Tiberiy Silvashi in a 1982 work titled Guest. Silvashi was the de facto leader of the Painterly Preserve, a collective created in 1992. United by a common attraction to the landscape and countryside and a keen interest in abstract formalism against the late Soviet backdrop, its members still exercised independent judgment when it came to theme and subject matter.

As evidenced by this painting, Silvashi employs blood red to pump the portrait of a man sitting in shadows with energy and allure. There’s an air of mystery, too. Nothing hints at the identity of the guest, but we know he feels comfortable enough to turn around the chair and hold the backrest between his legs. He shies away from the light waking up the right corner of the canvas. One would think he was punished, but his sinister grin says otherwise.

Nothing about this ample display of dexterity and subject matter feels particularly Slavic. The selection makes for an enjoyable viewing experience given its rich artistic merit, although it’s impossible to ignore the context during which it’s playing out. There’s a heaviness and emotional undertone throughout the show we can’t quite shake off. After all, these pieces are part of the cultural heritage of a nation whose sense of identity seems to be constantly threatened.

That serious, grounding quality is evident even in a small painting from 1985 titled The Game, featuring chocolate browns and a blend of greens and blues. Volodymyr Budnikov gives us a gathering of enigmatic figures in long robes standing around a round dish. One character to the left seems to be explaining the rules of engagement to the rest of the group. Thick lines delineate the columns and arches setting the stage while a concrete cone inexplicably floats in the background. The whole scene feels cold and cryptic and nowhere close to the playful attitude the title suggests. In fact, it’s doubtful this puzzling picture is meant to be witnessed at all by us, the viewers.

Look to Dmytro Kavsan’s Who comes last get the bones for the most explicit image of horror on display. The pile of bones on which blood and chunks of flesh still reside makes for a gruesome procession playing out under clay-colored arches. One of them bears the Latin words: Sero Venientibus Ossa (for those who come late, the bones). Next, we detect the discolored legs of two lifeless bodies dangling from the first arch in the foreground of this painting from 1986.

Socialist Realism demanded compliance with a recipe of pre-authorized forms and themes. This gave artists no room for experimentation and artistic liberty. Those who deviated from this formula were often censored or worse.

A 1964 small vertical piece titled Silence by Alla Horska, a fellow dissident artist killed in a still-unsolved crime, speaks to the frustration arising from ideological restrictions placed on the artistic community at the time. It’s one of several works included for historical context and to emphasize the persecution and oppression that preceded the rampant creativity of the perestroika years.

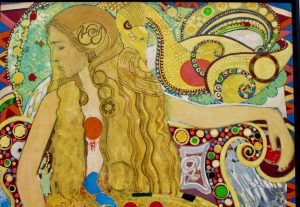

Gustav Klimt meets William-Adolphe Bouguereau in a piece by Horska’s husband, Victor Zaretsky. Leda depicts the Spartan queen resting on an armchair decorated in colorful mosaics while her golden locks of hair cascade down to her skirt. She looks away refusing to make eye contact with the swan approaching from the right and fusing with the background. This is Zeus in disguise. Leda’s pose is a clear indication of her discontent toward her suitor. Done five years before the aforementioned revival, the intricate ornamentation of her dress and setting already points to the excess and extravagance the title of the exhibition alludes to.

The spouses belonged to a group of artists from the 1960s known as the “Sixtiers” who early on rejected the principles of Socialist Realism and refused to let their artworks boost the interests of the Soviet regime. They paved the way for a future generation of non-conformist artists who soon would be liberated from the Soviet thumb and go on to create an eclectic catalogue of home-grown postmodernism and late modernist abstract painting.

This new, daring — albeit disorderly — production of art revamped Kyiv’s cultural scene and ultimately launched Ukrainian contemporary artists into the global scene as forces to be reckoned with. Most importantly, voices no longer seeking permission or a stamp of approval.

Painting in Excess: Kyiv’s Art Revival, 1985-1993, runs through Dec. 11 at the Coral Gables Museum, 220 Aragon Ave., Coral Gables. Hours: Monday through Friday, 12 p.m. to 5 p.m. Saturday and Sunday, 12 p.m. to 6 p.m. Admission: $12 adults, $8 students/seniors, $5 children (7-12), free to members of the military and children under 6. Call 305-603-8067 or visit coralgablesmuseum.org. All proceeds from the exhibition will go to relief efforts in Ukraine via Razom for Ukraine.