Long yellow shoelaces make for a wonderful sun, there is a vice versa to shoes are made from animals and while I don’t know about the white elephant, the black bear in the room is not always ignored.

I learned all of the above during a recent trip to the Boca Raton Museum of Art to check out two ongoing exhibits that are proving to be very popular.

More than 90 highly personal works created by ordinary men and women with no formal artistic training are the core of Outsider Visions: Self-Taught Southern Artists of the 20th Century, running through Jan. 8. The works here are humble in material and execution and, as we learn through the descriptions, often the results of a personal affliction, a divine revelation/vision or a favorite scenery.

Whether you are an art expert or only sat through a few credits of art history, you will feel that inner critic dying to point out that the proportions here and there are off, the composition seems boring and there is overall flatness. The temptation is especially irresistible with the first couple of works set against an intense red wall. They are perceived as childish; you can tell from the looks of those passing by.

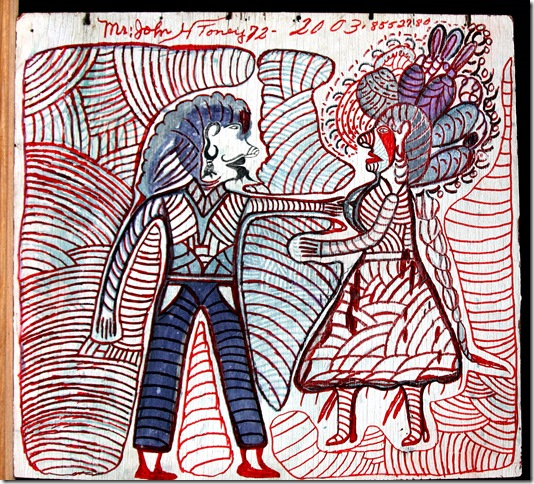

John Henry Toney’s That Man Is in Love with that Cutting Up Hairdo (2000) is an example of this. The use of markers along with the basic facial features and body shapes remind you indeed of a child’s drawing, but a child would have probably stopped after composing the main figures. That elaborate background you see taking over the entire white surface, as well as the linear patterns on the clothing, would have never happened. A child would have grown bored long before completing it and moved on to a new drawing.

Forget for a moment what you thought great art looks like. This is folk art, or outsider art, as the self-taught art genre is called. It does not have to be great or bad. It just is. And it is truly unique.

Despite the infantile traits, I found myself liking two works by Florida-born Mama Johnson titled Two Girls (2002) and Guess Who (2002). In both cases, two dots appear in place of the nose while bold black circular outlines make for wide-open eyes. A classic red mouth completes the face. In Guess Who, the use of frenetic lines, some bold, some thin, in red, black and blue, remind me a bit of Amelia Pelaez.

Alabama-born Jimmy Lee Sudduth provides some of the pieces that stand out the most: Red the Weenie Dog (2000) and Sawmill in Red (2000). The use of color in them – watch for the variations of browns, greens and pinks — along with the rich texture and raw finish, gives them a certain maturity and sophistication.

I love the irregular patches of blues and whites on the body of Weenie Dog. Here the animal appears horizontally stretched out against a bright green plain. If you read the description you will learn Sudduth, the son of a Choctaw Indian Shaman, grew up painting with mud and honey. For color he likes to use wild berries, grasses and coffee, among other materials.

Next to it is Black Bear (2006) by John “Cornbread” Anderson, a native of Georgia. The work, mostly in black, has a picture-book feeling to it. It seems to me perfectly fitted as an illustration for a children’s book. I suppose because I can imagine certain story line going on as the happy bear eats the honey and gets ambushed by the upset bees.

I found the strength of the show and its value to be precisely in the ability of these men and women to block knowledge and resist the traditional learning method that means sketching, cleaning brushes and having a group critique. It is a brave thing to resist the path that more or less promises systematic improvement. Come to think of it, improvement (as a goal) does not seem to exist for these self-taught artists. I got the impression they create because there is joy in doing so, not as a way to make a living and not expecting to become better.

But therein lays the good dilemma of Outsider Visions. One cannot be sure if an artist’s apparent disregard for the basic principles/rules of art is intentional or evidence of poor skill.

Even if the latter was the case, it does not necessarily mean we should dismiss the works. Actually, it could be interpreted as a sign of greatness. Pablo Picasso famously said: “In every child there is an artist. The difficulty is knowing how to hold on to this artist as the child grows up.” He also said: “…it has taken me my whole life to learn to draw like a child.”

In that case, these artists are masters at holding on to their inner child.

Does that mean knowledge ruins natural artistic ability? Not always. Before we get to Outsider Visions we have to walk through a jungle-like installation called The World According to Federico Uribe, by the Colombian conceptual artist.

Like the folk artists, Uribe is not a child. He is actually a very educated adult. He attended the University of Los Andes in Bogota and continued his studies in New York before moving to Miami. Yet he has managed to transform a 5,000 square-foot room into a silly uncomplicated world where alligators and leopards are made of sneakers, and leather and brown shoelaces become a monkey climbing a life-sized palm tree made of books.

This is what he is known for: giving every day objects unpredictable highly amusing new lives. The animals we encounter (a crocodile, a giraffe, a turtle, an ostrich, a zebra, a puma, etc.) all appear posing, as if suspended in the middle of an attack or reaction. This makes the show closer to real life.

For each of his inventive creations, such as the sheep made of ping-pong balls, we feel like rotating all around it to look at it from different angles. We want to decipher the recipe that gave it form. In most cases that recipe includes: Sneakers, pencils, shoelaces, books, discarded pieces of wood, corks, rubber soles and anything else you can imagine.

Also here are pieces from Uribe’s 2008 Animal Farm installation, which features a life-sized farmer family made of colored pencils.

Also running until Jan. 8, this is show that produces instant excitement. I watched adults and children enter and exit the room in complete amusement. Is it possible? Yes. Shoes are made of animals, so why not make animals of shoes?

I asked myself the same question and the answer was Yes, too. It is possible to go through formal education and have one’s imagination and innocence emerge intact.

The Boca Raton Museum of Art is at 501 Plaza Real, Boca Raton, in Mizner Park. Admission: $14 adults, $12 seniors, $6 students (through March 18). Hours: 10 am-5 pm Tuesday, Thursday and Friday; 10 am-9 pm Wednesday; 12 pm-5 pm Saturday and Sunday. Closed Mondays and holidays. Call 561-392-2500, or visit www.bocamuseum.org.