Memories in Mariko Kusumoto’s head do not need to fear a slow, eroding death.

Think of them like waves, retreating, seemingly forgotten, and later hitting the shore bigger and stronger, darker as well.

A unique and very personal show based on Kusumoto’s memories of Japan is currently on display at the Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens until May 6. Mariko Kusumoto: Unfolding Stories mainly consists of a series of metal sculptures that resemble music boxes or dollhouses with a surreal twist.

The exhibit is part of the museum’s artist-in-residence program.

A Greek/Roman sculpted torso rests on a pedestal while a wide-open eye serves as the round top surface of a tiny desk. If you move, the eye will open and close (as the image on a lenticular 3D postcard). The rook is a long-haired woman whose rescuer, a tiny knight, has started climbing up to the top using her braid. Look closer and you will see a man’s face has been given to a shell. These are all characters found in Kusumoto’s Chess Set (2010).

The pieces of this board game are meant to represent the East and West. It is not immediately clear, not to me at least, which side (East or West) each object was representative of. Here you will find them displayed across the board, but after a long battle, the pieces can go rest in a warm, semi-traditional Japanese home the artist has built for them.

Objects you would never think of putting together Kusumoto pairs in unimaginable ways, as in Shizuoka Ekiben (Boxed Lunch) [2006], where the elements needed for a tea ceremony are found in a sushi roll and a Japanese couple takes a stroll, umbrella in hand, inside a clam. Also, look for a tiny group of spectators anxiously watching a sumo wrestling match. The title of this teapot-shaped piece refers to the boxed meals available at Japan’s Shizuoka railway station.

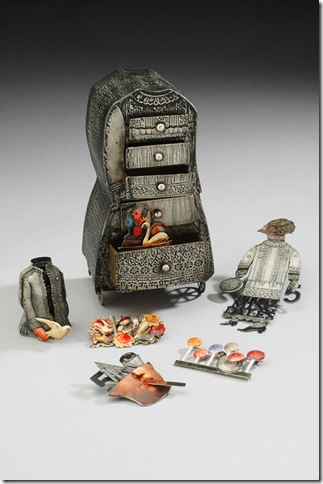

While visiting, you will see small doors and drawers open up to reveal a butterfly or a lipstick, a fetus or a sushi roll; each of them is a clue associated with a particular memory. They may have an entirely different meaning for each one of us. Participation is, after all, what the artist wants from the audience and we should not shy away from letting our own associations run.

Kusumoto’s amazing works derive from a childhood spent in a 400-year-old Japanese temple where her father was a Buddhist priest. It is the ancient treasures and daily activities she was exposed to as a child that she now pays tribute to and gives the overdue respect. She took them for granted, the artist says in her own statement.

That could explain why each of her works seems to say I’m sorry and thanks simultaneously.

Kusumoto uses techniques such as etching, enameling, chemical patination and electroforming, which is a metal built-up over a non-metallic surface as in the bronzing of baby shoes.

Her objects usually have a moving mechanism or some other magical surprise to offer.

Take Kodomobeya (Daughter’s Room) for instance. Each vertical body layer displayed reveals organs and stages of a pregnancy. To be exact, this is a representation of the artist’s pregnant body. She made it when her daughter, Misa, was one year old and drawing from the thoughts and emotions that transpired during this time of her life. It is the artist’s most intimate piece.

Unlike Kodomobeya, other box constructions cannot hold its containers within four walls and explode, instead, distributing the fragments of the memory among small theatre-like stages and making us work harder to find them.

Tokyo Souvenir (2008) features many of the iconic Japanese images tourists love. They include the good-luck cat (maneki neko), a local shop and people in traditional attire boarding a local trolley. The passengers are attached forming a bracelet and the cat contains a brooch holding the body of a parakeet.

The show is highly entertaining and far from overwhelming. We can easily walk it in 30 minutes, but you should really take your time. While doing so, you will sense Kusumoto not only enjoys working with metal but knows the material well. After all, she was assigned the task of polishing the metal ornaments of the temple’s altars as a child.

Personally, I was glad to see an artist not just frantically exposing elements of her childhood and herself but, in a way, also hiding them. The message I got from it all is that the child sees today what the adult will later discover. We ought to be grateful for Kusumoto’s arrival to the point of discovery.

Mariko Kusumoto: Unfolding Stories runs through May 6 at the Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens, 4000 Morikami Park Road, Delray Beach. Tickets: $12, $11 for seniors, $8 for children and college students. Open 10 am to 5 pm Tuesdays through Sundays. Call 495-0233 or visit www.morikami.org.

![Kodomobeya (Daughter’s Room) [2001], by Mariko Kusumoto. (Photo by Hap Sukwa) Kodomobeya (Daughter’s Room) [2001], by Mariko Kusumoto. (Photo by Hap Sukwa)](http://palmbeachartspaper.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/DaughtersRoom_frontcover_thumb.jpg)