The Atlantic Classical Orchestra’s concert Tuesday in Palm Beach Gardens featured four works, one a world premiere, conducted by Stewart Robertson, who will retire after this season.

Robertson opened this concert with a rarely heard Schubert overture, Die Freunde von Salamanka (D. 326), described in the beautifully prepared program as a singspiel, a German opera with spoken dialogue between numbers. It is a lighthearted piece with busy strings and busy woodwinds, almost Rossinian in character. Who borrowed from whom? No matter; this overture had all the warmth of Spain and a loveliness one associates with a Schubert symphony.

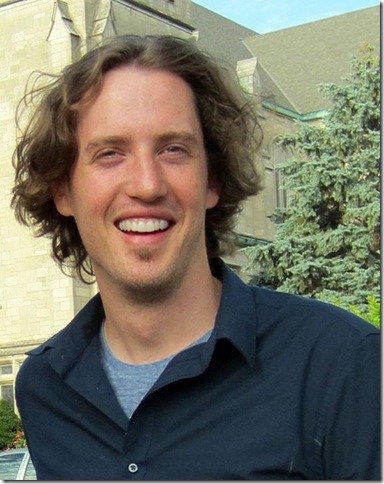

The second work, River of Doubt, was a newly commissioned composition by Seattle native Patrick Harlin, 31, a most promising talent whose music is easy on the ear. Inspired by the natural world, this young man traveled to the Amazon River basin to record “soundscapes”; at the time he was reading Candice Millard’s book about Teddy Roosevelt’s search for the headwaters of the River of Doubt (Rio de Duvida), which eventually joins the Amazon.

Described in the program as “not entirely programmatic music,” I think Harlin’s piece represents a musical journey on the river and conjures a place where few have been. It has three movements.

The first, “River of Doubt,” begins with eerie, interesting pizzicato sounds coming from the cellos and double basses heard over a soft, busy violin theme. A short-lived deep bassoon melody catches our ears as the percussionists work the timpani. Mystery is everywhere. Single notes in the woodwinds are eventually woven together by the full orchestra, which leads to a throbbing tune (shooting the rapids, perhaps?). A four-note upbeat tune on the trumpets is repeated by the trombones. They fade away. The contrabassoon ushers in a chugging single-stroke engine boat sound as the orchestra builds to a great crescendo.

The second movement, “Cloud Forest,” starts with flutes and woodwinds, after which the strings lead to quick, cheeky trumpet interjections and four solid beats from the timpani. The music flows along, river-like, for a while; here the influence of Smetana’s The Moldau was all too clear. Obvious raindrops appear the flutes, then high notes on the first violins are soon joined by the other strings as the music gets busier and in our imagination we feel the river getting wider in its upper reaches. A clean trumpet statement declares the immensity of it all.

“Rondon,” the third movement, is named for Roosevelt’s guide and co-leader, Candido Rondon, still a popular hero in Brazil. Brassy trumpets play a jaunty tune. Rollicking, dancing rhythms suggest Latin American music in the woodwinds and strings. The piano repeats two notes incessantly, followed by another big orchestral buildup. Low bassoon scales are joined the clarinets and as the piano decides to wander away from his two-note monotony; the flutes fade to nothingness as the piece ends quietly.

Before conducting Harlin’s composition, Robertson spoke of how new music only gets one hearing, which leads to the opinionated savaging its merits. My overall impression is that this young man clearly orchestrates very well and has stayed away from atonality. I feel he could have been more daring, more adventurous, in order to make this a committed, fully programmatic piece: after all, he is describing Roosevelt’s adventure, and his own trip there. And yes, I would like to hear it again.

Richard Strauss’s Horn Concerto No. 1 (in E-flat, Op. 11), written in 1883 when the composer was 19, was next. The son of Franz Strauss, a distinguished horn player, Strauss knew how to write for the instrument. The soloist was Brian Blanchard, principal horn of the ACO.

A massive orchestral chord opens the concerto, written in three movements that are merged and played as one. The soloist enters with some bravura playing that immediately establishes his credentials. The opening Allegro continues with a strong statement from the horn, answered twice by the orchestra. Now the horn returns with a graceful, lyrical theme, exquisitely played by Blanchard. And artful transition brings us to the second movement, marked Andante.

These new tunes are lyrical and romantic, and clearly demonstrated Blanchard’s even tone, good lungs, great breath control and magical gifts of playing this difficult instrument so easily. His playing reminds me of the late Dennis Brain, master of the horn, whom I was lucky enough to hear in London’s Royal Festival Hall before his death at a young age in a car crash in 1957.

The third movement, also Allegro, begins with difficult scales, nicely aced without fluffs by Blanchard, a remarkable feat. Raucous passages are spiced with sweeter melodies, setting off the horn fanfares to great advantage. Spaced chords from the orchestra lead to a brilliant ending with the horn sounding dominant, but not overbearing. Brian Blanchard is indeed a master of the horn, too.

After the intermission, the ACO performed Beethoven’s Symphony No. 2 (in D, Op. 36). Written at a time when he was having family troubles, his love life was a disaster and he was losing his hearing —“I shall defy my fate,” he wrote, “although there will be moments when I will be the most miserable of God’s creatures” — the symphony did not inflict these personal troubles on his public but simply represented the most stunning new music they were likely to hear.

The cellos stood out in the first movement, leading the lovely fugue that passes around the orchestra, and in the second, Robertson’s control of his forces was sweetly delicate. The string section sounded wonderful in the tightly compact music of the Scherzo third movement, and in the finale, this hard-working orchestra dug deep and played its best, giving a joyful rendition of a symphony that gives no hint of Beethoven’s travails.