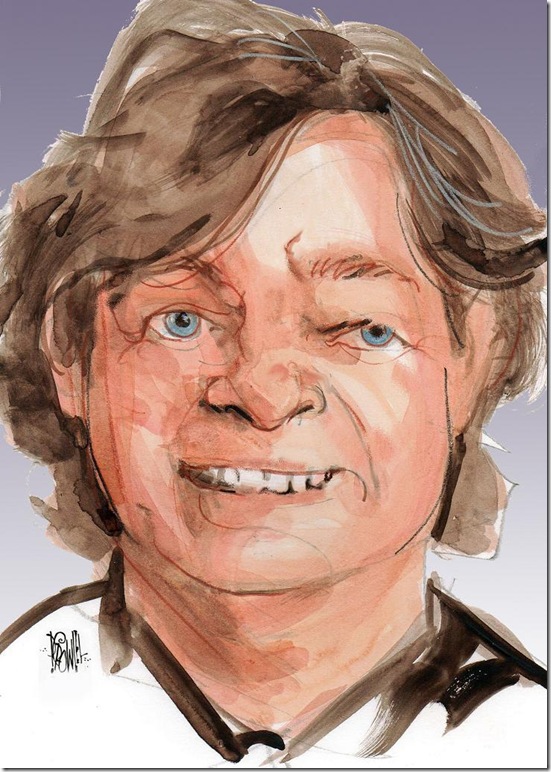

When James Judd takes the stage during the first week of December to lead the Boca Raton Symphonia and the Master Chorale of South Florida in three performances of George Frideric Handel’s oratorio Messiah in Boca, Miami and Fort Lauderdale, it will mark his first appearances with local musicians since 2001.

The former conductor of the Florida Philharmonic has been busy leading orchestras all over the world since then, notably as music director of the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, with whom he recorded frequently on the Naxos label, particularly in the work of Douglas Lilburn, New Zealand’s most eminent composer.

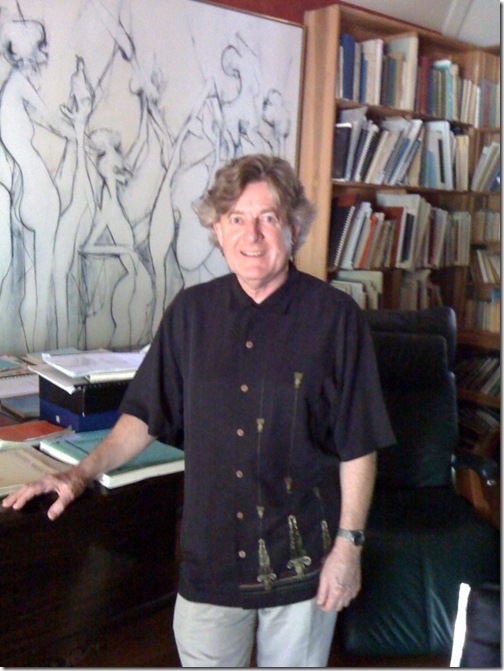

At 60, Judd’s home base is still a house in Fort Lauderdale, where he lives with his wife and daughter. The British conductor is currently heading up the Miami Music Project, a music-education initiative in the Miami-Dade County public schools working off a three-year, $1 million grant from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

Palm Beach ArtsPaper’s Greg Stepanich spoke with Judd on Nov. 9 in his spacious studio, once a garage but now given over to a piano, scores and books. What follows are transcribed excerpts of their conversation, with questions edited for length and clarity.

Stepanich: The Messiah performances will be your return to local stages. So, are you back?

Judd: Well, we’ve always maintained this house, actually. We’ve been here. My daughter’s in school in Florida. For a while we were living between London and Florida, and she had two schools. The notion was that my wife and daughter could be a bit closer to me, because now I work about a third of my year in Europe, about a third in Asia, Australia and New Zealand, and about a third in North America, South America. I work quite a lot in Canada, every year a few times.

But that became too complicated and crazy. So we’ve been actually living here, my daughter goes to school at Nova, she’s 15. We’re here, there just hasn’t been anything to do here. But now, the Miami Music Project, which I just volunteered for, that’s my passion. Locally we have this incredible opportunity.

So the chorus asked me: Would I like to do Messiah? And I had this time free, and I thought it would be fantastic. Because you know, we started the chorus all those years ago, and they were just getting better and better and better. And I thought it would be lovely, because I’ve done Messiah in different places in the last years, in Seattle, in San Antonio, last year was up in Ottawa. From time to time you get asked to do it, and I’m always thinking, you know, God, it would be so nice to work again with the chorus and with musicians from here. And it’s actually worked!

Stepanich: So you’re doing the complete Messiah?

Judd: Yes.

Stepanich: Not just the Christmas portion?

Judd: No. I’m a real believer that Handel was very careful about the way he organized the story and the way he wanted to tell it. And so when we can, I think we should try to perform it complete. It’s a wonderful drama, isn’t it? It’s not an oratorio, it’s an opera. At times it’s so amazing, the pacing is so incredible.

And so I love the timespan of it.

Stepanich: We see a lot of performances of Messiah at this time of year. It’s always struck me that a lot of it is very difficult for amateur choirs.

Judd: Well, there’s a lot of it, isn’t there? Last week, I was doing [Mendelssohn’s] Elijah in Australia, and realized: My God, there’s a lot of this. But there are two less choruses in Elijah than there are in Messiah.

I mean, it’s a huge sing. And as you say, not only [do] some of the well-known choruses require incredible agility for a chorus to sing properly in Baroque style, but a lot of the choruses that are not sung very much, so often for choirs are a new learn. And they’re wonderful pieces.

So I love the flow of it, I love the way he so carefully juxtaposes recitatives with solos, with chorus, and when you have this big span, when you come to that final Amen chorus, it really means something. It’s like you’re reaching the culmination of a great Wagner opera or a Bruckner symphony.

And you need that stuff before, you need everything, to really get the most out of it. It changes the piece, the spirit of it.

Stepanich: It may be that choirs of the Victorian era had an easier time with Messiah because they were more familiar with those styles …

Judd: I’m not sure, because that tradition of performing style of Baroque in the Victorian era, in the early part of the 20th century, was a very Romantic version. People did not appreciate, at that point they did not think about, Baroque style. They didn’t have the knowledge we have today.

On the other hand, [Messiah] started in Dublin with very small forces, but it quickly grew, and well before the 20th century, the late part of the 19th century, there were performances with hundreds of voices. And probably, just as with the Fireworks music, with the Water Music, Handel had hundreds of winds. You know, they would double the oboe parts.

It’s funny, today we think of Baroque music, also Classical music, the fact that Haydn, that Mozart, had a Paris orchestra of 100 musicians, is sort of inconvenient for us today to remember because we like to think it was small forces for everything.

Stepanich: And you’d like to think the composers were thinking, this is what we’ve got, but I’d sure like four horns there.

Judd: Of course. We learn everything we can, we keep up to date with performance practice and everything, but eventually it’s about the authentic spirit of the music. We’re going to have around 80 voices for this performance, and I like doing it with just three desks of firsts [violins], three seconds, very small orchestra, a Baroque orchestra.

Then you have this lovely mixture. When you need a bit of heft, you’ve got it, but when you need delicacy, you also have that, a small orchestra playing Baroque style for the solos. We also beautiful young soloists coming from Curtis [Institute of Music], which is lovely.

Stepanich: I remember seeing your Messiah performances with the Florida Philharmonic and being struck by the very brisk tempos in a lot of places. It seemed to fit with what Roger Norrington and others were doing with [Baroque and Classical] tempos…

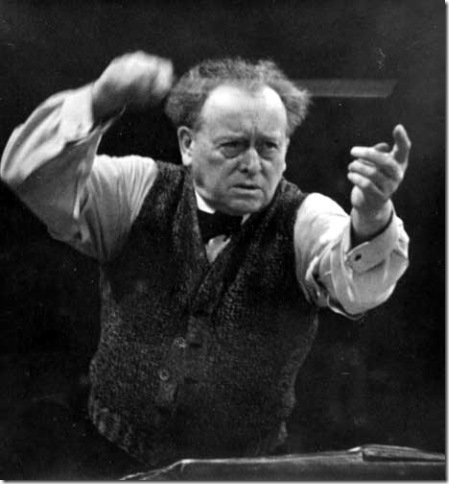

Judd: I think we think that more about Baroque music today. I think that there’s a great variety of tempo, because everything used to be a bit middle-of-the-road. After all, they were also performing Messiah in those versions like Sir Thomas Beecham orchestrated, with trombones and side drums and all kinds of things.

So everything kind of slowed down a bit, and there was a little [too much] uniformity of tempo for my taste. I think you have to go with the text, you go with the tempo of the text. There were no metronome marks, but there is a sense to the drama in the text that kind of dictates the tempo.

Stepanich: You’ve done Messiah many times. Do you go back and review the score each time and find something new?

Judd: Oh, yeah. That’s the fun of what I do. I do a combination during the year of new things all the time and old ones, and having time to just go back and restudy, and rethink, and just – well, first of all, there’s a natural progression I think comes, doesn’t it, just from performing. That fact that you’ve done something before, it’s going to be different next time. There’s a certain maturity or whatever you want to call it that goes on without any thought.

But when you have time to look and rethink things, there’s a lot to think about: What do you double-dot, and what do you not? The tempi, like you were talking about. And you rethink things also on the spot depending on the kind of soloists you have, on the chorus, the level of the chorus and so on. You find a way to get the performance together.

Inevitably, it’s going to be different everywhere you go. The tempi are going to be slightly different depending on circumstances, acoustics. But the rethinking, the restudying, is just one of the great joys and pleasures in life for me.

Stepanich: You’ve got different versions of the music, too: The pifa is longer in one, there are different soloists …

Judd: Yes, there are legitimate choices in Handel’s own time, not just swapping voices –– maybe this time on an alto, this time on the bass, could be either. Also, there are different versions of some of the arias, different time. He redid some of them, even changed some of them from aria to Recit., you know.

Stepanich: How does the English tradition with Handel differ from the tradition here in the States?

Judd: I don’t know that it differs a great deal. When I grew up, they were big performances. Every town had a choral society, 100, 200 people. And we grew up with performances with symphony orchestra.

But before long, the awareness of Baroque styles came, and it probably started in England. There were these scholars and conductors who started to do things well before Norrington and [John Eliot] Gardiner, a generation of new thought about Bach and Handel in particular, and so it started early there. We’ve got a big tradition in England, in Holland, in Germany, of not only Baroque music but Classical music, about the use of vibrato, about the articulations of music.

But we’ve got to the point now, which I find very, very interesting, if you look at people like [Nikolaus] Harnoncourt, who’s worked a lot with the Vienna Philharmonic, with [the Amsterdam] Concertgebouw, for example, with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe, with traditional instruments but getting people to play in what they perceive to be authentic style. Although Harnoncourt — I know I heard him interviewed one time — said, Look, I’m not doing authentic Bach. All I can do is authentic Harnoncourt. Which makes the point, modestly.

But it’s interesting now that in European music schools, and I think more and more in this country, students are being taught to play in these different styles. If you’re now a string player coming out of the London Conservatory, and you’re asked, you will play Baroque style on a modern instrument. You’ll know how much vibrato to use, the sort of bowing and what’s expected. And more and more, I think, symphony orchestras will be, at the request of a director, able to play in different styles: Mozart this way or that way. And I think that’s fascinating.

Stepanich: What’s also interesting is whether musicians will be asked to be conversant with, say, the period practice of the Mahler style, with portamento.

Judd: That’s something I feel strongly about, because that tends to be neglected. People are too shy about that performance style. But if we listen back to [Dutch conductor Willem] Mengelberg, listen to the recording of Mahler Four — and you know, I’ve studied his score, and Mengelberg marked all these things which are incredibly extreme by today’s standards, but it’s probably a damn sight closer to Mahler than what we tend to hear today. But it’s not convenient. You have to accept that Mahler, who wrote so much detail into his score, [that] that was still only just the beginning.

Stepanich: I think conductors have an unusual problem, and we’ll take Mahler since that’s what we’re talking about, in that they have to try to identify with a mindset that’s impossible to re-create.

Judd: Well, that’s exactly it. For example, you listen to the Mengelberg [Mahler Fourth] recording of the ‘30s. Look at his score, which is there in The Hague for you to study. Read the letters between Mengelberg and Mahler, listen to Mahler’s piano roll, listen to the other performances of the era, read what Mahler had to say about Bruno Walter as opposed to Mengelberg, read what Mahler said about the Vienna Philharmonic’s preparation and the Concertgebouw’s preparation, go and look at the scores – I’ve done all of this – go and look at the score of Mahler Four in Vienna that they have, Mahler’s conducting score.

And even in that score, for example, the horn parts – 1, 2, 3, 4 – he has arrows to say: In the Concertgebouw, this way around, in the Vienna Philharmonic, this way. So he was thinking so practically all the time. But you know, when you put a lot of that stuff together, the circumstantial evidence, you begin to get a picture of a very different sort of performing.

Stepanich: Did you ever get to a point where that picture crystallized in your head?

Judd: Yeah, I think so, but it’s constantly changing, your perception of these things. And what you’re fighting sometimes is safety. I’m lucky enough to work with wonderful orchestras all over the world, but wherever you are, sometimes you’re fighting a tradition where people are frightened to take risk.

And one of the things, to realize some of these ideas — for example, portamento you talked about. Today, people are embarrassed, often. You say: “Play portamento,” then they play it in a certain way, but the fingering was very different in those days, a sort of shifting, and you have to do it that way, or it doesn’t sound right. It just sounds clumsy. And you have to do it because you really feel it. If you can get an orchestra doing that, then suddenly the music transforms.

…The gulf between how they used to play Baroque music and now is kind of understood. We know the pitch was different, we know more about it, as far as we can guess. But the sort of end of the 19th century, the beginning of the 20th century, to now, they were just as different. I mean, look at the way the orchestra’s changed. Look at the orchestra for The Rite of Spring, the sound of the instruments.

Listen to Elgar’s recordings of his symphonies: even in the early ‘30s, late ‘20s, in England they were still using gutty strings on the violin, even though the metal were available. Strad magazine advertises them from the 1890s. But they couldn’t afford them, probably, in England, so they’re all gut strings. It changes the sound.

The woodwinds in England were still French woodwinds. They were using these pea-shooter tiny trombones, so when Elgar writes “fortissimo,” you still hear the pungent French bassoons playing, it doesn’t drown the strings. So you have to understand all that. And you have to, these days, often with orchestras that don’t necessarily know that, you have to explain a little bit of that, otherwise it’s going to sound overblown and ridiculous.

So there’s so much, it’s so fascinating. I always like listening to dead performers: just listen, not copy, just listen.

Stepanich: Tell me a little bit about the Miami Music Project.

Judd: It’s been in the making for a number of years, actually. And it’s various ideas which have fused together. And so what we are left with is this:

Some time ago, I was put together, so to speak, with Richard Harris, who was a trombone player with the New World Symphony, who was very, very keen on similar ideas. And I’d known Richard a little bit, we’d met before [and decided] Yeah, we can do this.

So we were very lucky to receive a feasibility study project from the Knight Foundation initially. It was about three months in the making. We talked to all the arts organizations in town because we’re a collaborative organization, we’re not trying to pretend we know the answers to everything. But we tried to see where the need is. Richard, with his small team of volunteers, was going around, and thanks to the cooperation of the arts organizations in town – it’s [Miami-]Dade County we were concentrating on initially — questioning audiences about what they would like to have, and what they thought was missing in classical music.

We produced a big feasibility study which was very thorough, and as a result of that and all the long process, we were lucky enough to get a grant from the Knight Foundation for the Miami Music Project of $1 million over three years, which we have to match. And I do it as a volunteer, like I am for the Messiah; I think we’ve got to give back something, we’ve got to really do something for the arts. I have a great experience going and working with great orchestras all over the world and doing concerts and being well-received or whatever, asked back: that’s great.

But there’s something missing everywhere, and that is everybody’s searching for the new generation of concertgoers. Everybody’s searching to redefine, a little bit, orchestral life. The New World Symphony Orchestra does it in an amazing way down in Miami; that’s fantastic. I’ve always felt that we’re looking for young audiences, everyone wants new audiences. Well, why would young people be interested in what we call classical music –which I hate as a title, anyway, but it’s all we’ve got, I suppose — when much of it is just subscription concerts, more or less?

I always use the example of Beethoven. Even when we play the Eroica Symphony, for example, there may be a very good program note, the conductor talks about it and we discuss the fact that Napoleon was his hero, then he scrawls the name out [on the symphony’s title page] on realizing he was no democrat. And Beethoven is there in troubled circumstances, with the French bombing Vienna and so forth.

So he’s not writing a familiar subscription menu for us, he’s writing music that is absolutely communicating with people, with issues. He’s writing politically cutting-edge, he’s writing as a humanitarian to connect with people, and today they tend to be, at best: Well, that was a nice whistleable tune.

More and more, I feel, we’ve got to get back to what was the cutting-edge reality of this music. And it might be that it poses difficult questions for us. And you can’t isolate music, or music education, from other things in our society. And if we want a proper society, we have to realize culture can be, in a way, dangerous to politicians. It teaches people to ask questions. And I’ve been very afraid that there is a large part of our community, that despite the great teaching available, the resources for the public schools have been cut, cut, cut, cut, cut.

And it’s sort of convenient to some political mindsets not to have culture, not to have part of the community properly educated generally because we can keep them in fear, and not asking questions is probably very good, so that [Rupert] Murdoch can preach to them. I dare say it looks a very deliberate policy over a certain number of years. And then you tie them up with ludicrous exams, SATs or whatever that nobody likes — I haven’t found a single person — it may be convenient for some, but it seems to me to be a very daft way to educate people, with all due respect.

So we thought: “How can we address some of these things? How can we help a little bit with education? How can we put in the minds of people that some of this great music we’re listening to has another dimension as well, if you’d care to think about it and let yourself go into that arena?” So we decided we would audition an ensemble of musicians, however many we can afford. We started off by auditioning for 10 musicians all over the country, the best talents we could.

We selected the musicians, and the goal is, this year we have 10 adopted public schools in the Dade system, 200 kids in each school, 2,000 kids, on a regular basis with our ensembles, sometimes it’s a smaller ensemble, sometimes a larger one. As we get the finances together hopefully it will develop.

My principal responsibility right now is to raise the money. We’ve got a basis of an extremely good board, and now, you know, it’s a big ask, but it’s doable. But we decided to start a little bit smaller than we originally wanted. There’s a thirst, there’s a need, for as many weeks as we can possibly do. It’s been incredibly well-received.

Stepanich: There are those would say that kids need to be studying math and science, and that music is not necessary, it’s just a frill. I would guess you’d disagree with that.

Judd: Of course. It is necessary. It’s just a political convenience to say it’s not necessary. Music is around us all the time. It’s just a natural human state. We were probably making music, making vocal noises and singing, and had rhythms, before we had language. It just can’t be denied.

It also is a cliché that it is an international language, that wherever you are in the world and you play a minor chord and a major chord: Which is happy, and which is sad? For some reason, everyone’s going to know. When you play a fast rhythm, a slow rhythm, everyone’s going to know which one is going to be exciting, which one is funereal. Why? Why?

So it’s nature, it’s just nature. So don’t ignore it. And as we then go further and further, we realize then the power of music to manipulate, if you want – that’s a derogatory term – but to affect our emotions, or how we can manipulate our emotions with music. This is what composers are doing, they’re bringing us all together.

More and more, the popular music culture has become quite aggressive. It’s quite tough and hard. I think more than ever we need to, through education, not deny that — I enjoy listening to that, my daughter has taught me a lot about a lot of music I didn’t know existed, and I can really get into it. It’s not one or the other at all.

The great thing about so-called classical music is that the kids they’re used to an age where we concentrate for short soundbites, where music is all about pretty hard rhythms, sometimes very cool, lovely melodies and beautiful lyrics as well, but I think for the most part there will be a tremendous need for music that gives more space around them. I think the sort of music we offer can provides absolutely a sort of oasis, a therapeutic and healing oasis, and by listening to such music, it develops sensitivities, it allows sensitivities to emerge.

And of course, the other side of it is, as you get to listen more and more, and music can teach you to listen, then you start to hopefully listen to language of your neighbor, and language of somebody who looks different from you, and then maybe you’ll start listening to politicians and realizing that you’re being sold rubbish. You know, you start to demand more than the Murdoch headline.

Stepanich: I wanted to ask about New Zealand briefly. You’re now the emeritus conductor of the New Zealand Symphony; is there state support in that country for music?

Judd: Oh, yeah, and it was amazing there, still is. The government really underwrites the orchestra, basically. Anything extra you want to do, you have to find some extra money. For example, while I was there [1999-2007], we did a few tours. We went to the Proms [in England], we went to Japan a couple of times, we went to the Concertgebouw, we were doing lots of recordings. And if you want to start doing that stuff you have to find some other government funding, maybe trade and tourism. And you have to find some individual money, but there’s not a lot of individual money down in that part of the world. There’s no tradition of giving. So there’s always corporate underwriting.

Basically, while I was there, we had this incredible prime minister, Helen Clark , who is now the No. 3 at the United Nations [head of the U.N. Development Program). And she always went, before she was prime minister, bought tickets for everything: symphony, ballet, opera, loved music. And music there, they have an absolutely fantastic music education still in the schools. And I was so impressed being there, and I got to know her very well. We used to have dinners with her and her husband, when my wife was in town, with guest artists, just talking about life.

And I was so impressed, there was a woman who had an idea of how music was connected to how we look after people’s health, how we look after the Maori and the Pacific culture. You know, everything glues together. It’s a natural part of life. And it’s a fantastic example.

It seems to me to be so awful when we give things labels. You would call it a socialist government, but what is a socialist government? It’s just so daft that these labels get given, like “liberal” and “conservative” in this country. Liberal in this country would be sort of a Conservative government in England.

This health care thing I think one has to talk about in connection with music, because if we’re so ungenerous, so inhuman, as to not understand that everybody should have health care, and we use these awful arguments protecting just the insurance companies. Look: I don’t know any conservatives in England who would ever speak out against everybody having the same kind of basic health care, or paying taxes to do that. I mean, it’s part of being a human being. And that’s a problem. It’s a problem.

Because if we don’t understand as human beings that we have to not just pay lip service to, but genuinely just give a little bit more of ourselves if we can afford it, so everybody can have basic health care, so that everybody can have a basic good standard of education, then how on earth can we understand what music is, how on earth can we do it? This is troubling, deeply troubling.

Stepanich: Although we’ve had a lot of problems in music education these days, technology has helped classical music a lot in that it’s gotten rid of barriers such as getting dressed up and going to concert hall for a lot of people. So has it been a double-edged sword?

Judd: I think it’s a good thing. Having said we’re searching for these new audiences, I think we’re in a period where we’re searching for a lot of answers and we’re beginning to find them.

First of all, if you look around, there are more concert halls than ever before. We’re still building concert halls, right? All over the world, and in the United States. More people are listening to classical music than ever before. Now, the big recording companies, the few big ones that there used to be before Naxos was so successful, those became disinterested in classical music, didn’t sell enough, didn’t have enough profits, so they disappeared.

So the headlines were: Classical music is dying. That’s rubbish. The problem we have is, as you don’t educate people in music, decision-makers, be it politicians, individuals, philanthropists, corporate leaders, have no music in their background, therefore, they don’t understand value-cost arguments. It’s like you couldn’t build St. Paul’s Cathedral today because it would be impossible to heat. The bottom line would be so ludicrous they’d say: “Build it 10 times smaller.” But it’s there.

It’s like with Beethoven. If we’re going to keep Beethoven alive, we have to have orchestras to perform it. If we sell out every ticket in a modern hall, we’ll struggle to probably get 25 percent of box office of the costs. But if we want Beethoven to survive, somebody’s going to have to find money for that.

I think government should play a bigger part, because if it considers that music is important and it should — and it’s wonderful to see Obama at least has had that Classical Day, he’s had a Jazz Day [at the White House]. But we need more than that. We need money from a few missiles to support a few orchestras, a few ballet companies, opera companies. Think of what it would take. Nothing from the national budget, nothing.

Stepanich: I was talking with someone the other day about large and small orchestras, and whether large orchestras are really sustainable these days, and whether you couldn’t just get an ad hoc larger orchestra together when you need it, but otherwise stick with smaller orchestras. I wondered what you thought about that.

Judd: You can have small orchestras, but for the most part they don’t work very well, and the reason is an obvious one. The public, especially in this day and age when we’re trying to attract audiences, likes the bigger pieces. They like the Romantic repertoire. If you try to play that Romantic repertoire with four desks of first violins, and in some places they have to try to do that, it doesn’t sound good. You’re not going to get people coming back.

I often use that argument: You go into a museum, and the museum buys beautiful Renoirs, and it decides that it wants to have smaller walls, and so cuts the Renoirs in half. I mean, you can do it if you want.

I also have one overriding thing, and that is that quality matters. I remember when I was assistant conductor in Cleveland years ago, and the belief was you always are the Cleveland Orchestra, whatever we do. We go into a high school, we take Cleveland Orchestra quality, because kids know quality. And anything that’s not first-rate quality won’t survive. It just won’t. It’s just nature.

Because everything artistic has to be competitive, you have to be better at what you do tomorrow than you are today, you have to. So you can’t fight that, as economically nice as it would be to do. And look, I believe you can probably have a symphony orchestra that has a basic six double basses instead of eight, and adds to them sometimes. There are orchestras that are really just large chamber orchestras in the world, that add players, but people are never happy doing that. There’s always a compromise, and the compromise often is just too much.

Stepanich: Which brings me to the Florida Philharmonic: The funny thing about its demise is that it just doesn’t seem like it should have happened. And I think it seems that way to a lot of people.

Judd: I feel the same. There were just a series of circumstances that kind of somehow worked together, and contrived for it just to happen. And it happened. And so many people did the best they could. Everybody acted in their best faith, everybody tried to do their best to try to find a way out of it. None of us could, and it happened.

It’s sad, but my own perspective on things is yesterday becomes history very quickly to me. And I have, in my life, I always have so much to do, that it’s not that I am not caring about the people who lost their jobs, I’m deeply caring about that. It’s just awful, the way the poor musicians have to scrap around. This is really, really tragic.

But, you know, tomorrow is another opportunity. I don’t have any room for negativity. I just don’t have the energy for it. I used to let things get on top of me, but I learned several years ago now [to] just forget it. I’m only interested in working together with positive people, and trying to do something. Whatever we do in music, we have to try to make an impact with it, and believe in it, and perform with a genuine passion, not a contrived one.

And if we’re going to do education, we’ve got to do it for the right reasons. And if we’re going to keep orchestras alive then orchestras had better perform and look like they mean it, and play well.

It’s a fascinating time. Now, with these incredible initiatives of the Knight Foundation, this fantastic concert hall we have, this opera house, the New World Symphony building their new hall: this is going to become one of the centers of art and culture. Look what’s happening in the visual arts world in this area. The fact that we don’t have a fulltime resident symphony orchestra is a shame, but it mustn’t take our eyes off the fact that there is now so much happening.

Messiah will be performed complete this coming week at three different South Florida venues. James Judd will lead the Boca Raton Symphonia, the Master Chorale of South Florida and four Curtis Institute soloists — Sarah Shafer, J’nai Bridges, Joshua Stewart and Thomas Shivone — in George Frideric Handel’s oratorio at 8 p.m. Friday in Miami’s Trinity Cathedral, at 8 p.m. Saturday at Spanish River Church in Boca Raton, and at 2:30 p.m. Sunday at the Broward Center for the Performing Arts in Fort Lauderdale. Tickets: $30 in advance, $35 at the door. Call (954) 418-6232 or visit the Boca Symphonia and Master Chorale Websites.