“Jazz is not dead,” Frank Zappa said in 1973, “it just smells funny.”

It’s documented on the song Be-Bop Tango (Of the Old Jazzmen’s Church), from the 1974 live album Roxy & Elsewhere. And the master satirist was playing with one of his jazziest ensembles, which included keyboard-and-vocal icon George Duke and future Weather Report drummer Chester Thompson.

That was 36 years ago, and Zappa was in Hollywood, Calif., not Hollywood, Fla. Yet the late guitarist, vocalist and composer managed to capture the peculiar scent of jazz in South Florida — where there’s a history of topnotch learning institutions and musicians, but not the jazz scene and audience to support them.

Like many good things, jazz isn’t likely to completely die out anywhere, and South Florida isn’t the only region where it doesn’t flourish. But some of the area’s top jazz educators have certainly noticed something fishy about the genre, from internationally to locally. And the reasons they give for it vary — from natural to negative; academia to American Idol; and economics to more open-minded students, instructors and programs than in past generations.

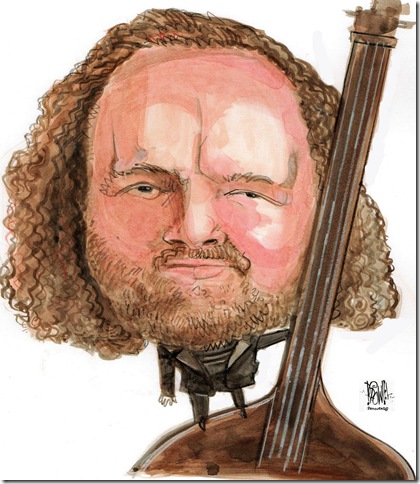

Bassist Chuck Bergeron earned his master’s degree from the University of Miami music program in 1985, and has been an instructor there for the past nine years. He says that UM — which featured two of the leading jazz figures in recent memory among past students and teachers in guitarist Pat Metheny and bassist Jaco Pastorius — may be just as renowned for its non-jazz curriculum.

“The jazz program at UM is one of the most versatile in the country,” Bergeron says. “It features concentrated study in many different traditional and contemporary styles, with an open-minded approach to preparing students to become professionals in the real world. I do many things within our program, including directing our 17-piece R&B ensemble, coordinating our small group program, conducting one of the big bands, and teaching classes in both jazz and rock history. And, of course, I also teach bass.”

Bergeron also plays what he preaches. He’s recorded and toured internationally, playing everything from swing to rock with the big bands of Buddy Rich and Woody Herman and the smaller groups of Kevin Mahogany, Arturo Sandoval and Elvis Costello.

UM’s Frost School of Music continues to stay at the forefront of both traditional and transitional jazz education. The school hired jazz pianist and arranger Shelly Berg, formerly an instructor at the University of Southern California’s Thornton School of Music, as its new dean in 2007. Pop pianist and vocalist Bruce Hornsby, a UM alum, also donated money to institute a songwriting program called CAMP, for Creative American Music Program. Its various courses and workshops cover all American roots-music styles.

“Shelly Berg’s presence has made a huge difference,” Bergeron says. “Our facilities have been updated and new buildings are in the works to house one of the most modern music schools in the country. As a professional musician, it’s great to work for someone who is also an artist and professional musician.

“We can be in an intense faculty meeting about the curriculum in the morning, then share the bandstand later that evening. Our music business and industry programs, along with Bruce Hornsby’s songwriting program, are at the forefront of modern musical education,” he said.

At Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton and Palm Beach Community College in Lake Worth, the rules and histories are a little different. Neither school has the musical pedigree of UM. Then again, Scott Henderson (who would go on to be named the world’s top jazz guitarist in both Guitar Player and Guitar World magazines) studied at both, and used his training to forge a playing style that includes jazz, rock, funk, blues and world music.

Like UM, FAU can touch upon some such non-traditional jazz styles within its jazz studies program by nature of being a four-year university.

“We are very proud of our commercial music program, led by our eminent scholar, Michael Zager,” says Tim Walters, trumpeter and director of jazz studies at FAU. “Lots of commercial music majors are avid jazzers, and they can get a great foundation in the creative, technical and business aspects of the industry at FAU, as well as increasing their jazz knowledge.”

Walters, who got his doctorate from UM in 1989, has been teaching at FAU since 1982.

At PBCC, the nature of getting a two-year associate’s degree allows for less wiggle room for music majors. Trumpeter Dave Gibble, who got his master’s from the University of North Texas, is the community college’s associate professor of music. He’s coordinated instrumental ensembles, concert bands, jazz combos and big bands there since 1995.

“We have to try to get students graduated with 60 credits,” says Gibble. “And as it stands, a music major usually has a minimum of 68 credits. So most of what we have to do is fairly standard — jazz combo, jazz big band, and maybe an improvisation class.”

Like Bergeron, Walters and Gibble also perform live, albeit both more regionally. The two trumpeters even play together in the Jazz Rats Big Band, artists-in-residence at FAU, as well as the PBCC Tuesday Nite Big Band. Instructors performing live, and conversely musicians teaching, isn’t a new trend. But the professors do see more students than ever before coming out of school to conduct both functions.

“I would say most, the majority, will play and teach,” Walters says. “I only know a few players who can make it on playing alone, and those, as with most of us, play jobs of all descriptions, not just jazz. And those of us who write and play jazz do it for love, not money.”

Jazz musicians have pretty much played for the love since rock, R&B and other genres grabbed more of the attention (and profits) more than a half-century ago. But jazz musicians have learned to adapt by playing other genres for money while pursuing their art of choice for the love.

In New York, jazz musicians used to wear a badge of pride if they didn’t have to play a Broadway musical or teach to earn a living,” Gibble says. “But now they’re realizing that those avenues provide some consistency and stability.”

The area instructors all agree that music education within the United States is lacking from the grade school through high-school levels.

“Music classes that we once took in middle school are no longer offered,” Gibble says. “So students who go into college aren’t even as likely to know what instruments are in an orchestra or big band. They have no exposure to music other than what they get in contemporary culture, whether it’s American Idol, the radio or whatever’s in the Top 10 on iTunes.”

Ironically, that’s not as much the case outside of the United States.

“Jazz is doing quite well in Europe, Japan and Thailand,” Walters says. “There’s lots of government support, especially in Europe. If more Americans knew what a treasure jazz is, as one of America’s few original contributions to the arts, perhaps there would be more of it to be heard here, and in more places. Wynton Marsalis is a crusader for this, and has done a lot of good.”

As one of the leading trumpeters of the past 30 years in both jazz and classical styles, Marsalis is also an esteemed educator, artistic director for the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, and the leader of its Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra — and therefore in good position to lead a jazz crusade. Many have followed his lead of being both a touring artist and educator, which may be fueling a trend. More live jazz performances are now occurring in educational classes and clinics as jazz clubs dwindle.

“I definitely see that trend,” says Gibble. “In the ’40s and ’50s in New York, you learned to play jazz by going to 52nd Street, hanging out, listening at clubs and finally getting your chance. Now you go to UM, the University of North Florida or the University of North Texas. The school is kind of taking the place of the gig scene, at least as far as learning.”

“I think it’ll be a combination of the two,” Walters says. ” “Learning to play jazz has definitely shifted away from the street-apprenticeship system, but jazz musicians are a pretty resourceful bunch when it comes to finding places to perform.”

Much of Marsalis’ emphasis has been on blurring the perceived divide between jazz, with its emphasis on open-minded improvisation and its move from big bands to smaller groups, and classical music, with its strict sight-reading and orchestral mindsets. Lincoln Center being home to one of the nation’s leading classical conservatories, The Juilliard School, helps the cause.

“People see a gap between classical and jazz,” says Gibble. “But I see classical as another style, and one that you can play better if you learn the harmonic, melodic and rhythmic language of jazz. Classical is a different approach, and teaches you how to maneuver around the instrument; to think about it differently and use a different skill set.

“But a good jazz player should now be able to play classical music pretty well, since they’ve had to learn to be somewhat chameleonic musically, and the two styles do present some similar difficulties. There’s more of a crossover than most people realize, because if you want to work as a player, it helps to be able to do it all.”

The instructors have all been teaching for long enough to watch a renaissance in their profession through technology.

“Lester Young used to learn to play by listening to records, developing his ear, sound and style,” Gibble says. “Nowadays, the jazz student has more tools than they can possibly utilize.”

Walters agrees. “Even the home computer was in its infancy when I got my bachelor’s and master’s degrees. What a different world now!” he said.

Bergeron, too, said technology has changed many facets of music education. “All of our students are required to have computers, and take classes in the industry standard software programs such as ProTools, Logic, Sibelius, and other sequencing and scoring programs,” he said.

Perhaps as a sign of the jazz scene shifting from clubs to classes and clinics, music enrollment at UM, FAU and PBCC remains steady during the economic recession as the area jazz scene has otherwise declined.

“Restaurants are having a tough time, so they’re less likely to hire musicians,” Gibble says. “I don’t know of any jazz clubs in West Palm Beach anymore. Fort Lauderdale has clubs that now only offer jazz on certain nights of the week, and Miami is down to just a few jazz clubs. Performances outside of the schools seem like they’ve moved more toward festivals than clubs. And we have so many things to do in South Florida other than go hear live music.”

“I’m not sure there’s a place anymore where you can regularly hear a big band, besides in the schools,” Walters says, before presenting a ray of hope. “But I think there’s a small-scale renaissance of interest in jazz here. A few weeks ago, Art & Jazz on the Avenue in Delray Beach had quite a fine lineup.”

That glass half-full attitude is something he offers when students question him about jazz, and the opportunities it still presents.

“They want to know about the future of the art form,” Walters says. “And I tell them there will always be room for one more fine jazz musician. Especially one who also has classical training in reading and technique. They’ll have many more playing opportunities than those who are more restricted.”

Bergeron said he knows there is still plenty of audience interest in the art form.

“It’s funny, but every time I perform in Miami, Broward or Palm Beach, the audiences are always very appreciative,” he said. “So I know there’s a desire for great music. We just need more venues where we can reach a wider audience, and nurture this beautiful music well into the 21st century.”

Bill Meredith is a freelance writer in South Florida who has written extensively about jazz and popular music, including for Jazz Times and Jazziz magazines.