Better than looking at art is to be part of its history and development or, better yet, to have a personal association with it. Since we cannot all be muses, we take the next best thing: being the first to see it.

An ongoing exhibition at the Norton Museum of Art offers that opportunity through March 29.

A strong personal voice fills the galleries housing porcelain and glazed stoneware sculptures by Sweden-based artist Klara Kristalova. It is a muted voice but very present nonetheless. Transformation is the recurrent theme here and is first aided by a somber setting featuring dark walls.

The figures appear frozen in mid-reaction, as if not allowed to complete a natural response. Their glossy finish highlights the stillness and drama of the moment in which they are caught. This is Alice in a much darker wonderland.

Klara Kristalova: Turning into Stone is the artist’s first solo museum exhibition in the United States and the fourth in the Recognition of Art by Women (RAW) series started in 2011 by the museum to highlight living female artists. It includes a series of intimate drawings.

Among the most intriguing works begging to be explored is The Sleepless (2011), which features several wild creatures (a fox, an owl, a hare) looking over a sleeping girl whose head is considerably larger than the rest of her body. The wide-eyed animals stand as the product of the girl’s imagination or possibly an elaborate dream she is having.

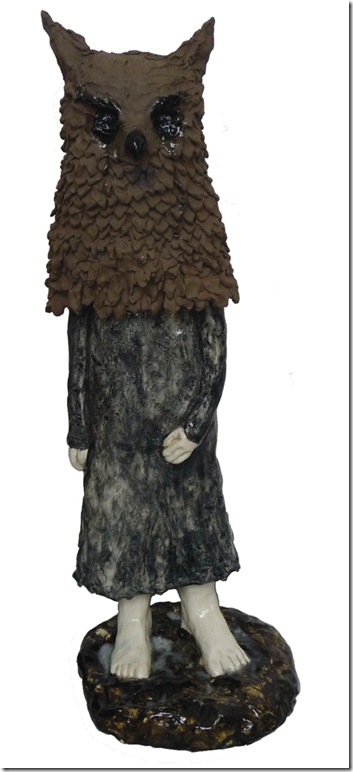

Despite the visibly sharp teeth on the bear-like figure, nothing appears menacing. Kristalova uses her hands to give her characters form. That explains why works like this one look far from perfect. Rather than producing a classical or realist interpretation of the world, the Czech-born artist fleshes out invisible emotions and gives them a face or — in the case of Birdwoman — a beak.

The feelings of embarrassment and shyness are cleverly portrayed by the sitting figure wearing a donkey head in Anonymous Guest (2009). Its slouching posture suggests a lack of confidence or fear of showing one’s true self. It is one of several hybrid characters included in the show and the complete opposite of Birdwoman (2013), which embodies empowerment and maturity with her pointy black heels and white feathers, and despite her sagging breasts.

It is not by accident that the gestures and poses on display come across as creepy and playful, turbulent and relatable. There is something to the hands-on approach the artist employs and the medium she chose to work with, but universal concepts such as anxiety, insecurity, pain and loneliness are the key. They are expressed through deformities, masks, predominant eyes and dark or muted colors with a muddy quality. The resulting characters are mysterious but approachable.

Few are more disturbing than The Catastrophe (2007). The scene portrays a girl vomiting a black liquid substance that is also coming out of her ears. As if it wasn’t bad enough, she seems to be sinking in the black thick puddle forming around her.

The artist’s admission that some of her inspiration comes from living in the woods by a lake outside of Stockholm comes as no surprise. Branches, roots and leafs appear throughout the show as do moths and butterflies. The insects are overwhelming in And still they remain (2009), to the point that the face of the girl is hardly visible and in danger of being eaten away by the black-wing monsters. Strangely enough, she does not fight them off.

The story goes that, having witnessed first-hand a swarm of moths around her home, Kristalova was taken by their beauty only later to feel disgusted by them. This tendency of combining reality with fantasy and negotiating the line between horror and innocence is her specialty.

Be sure to visit the last gallery room containing her latest creations, some of which have never been shown before. They include a series of busts and larger-scale works that challenge the viewer the way children grow up to confront parents.

One in particular seems to speak to the transformation taking place at the self-conscious level, not so much the physical one. As many of her children sculptures, the featured girl wears an owl head serving as a mask. She stands barefoot while carrying the dark brown mask that heavily comes down to her shoulders. This is The Owlchild (2009). It is rather troubling to look at and does not convey much fun.

Kristalova’s ability to visualize and give shape to the complexities of human emotions is the highlight of Turning into Stone. Ceramics was not even the artist’s first choice. It only followed her disappointment after studying painting at the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm. In her hands, it has become the perfect tool for airing inner fears and surreal thoughts.

Judging from her works, these emotions can be disturbing, confusing, raw and even scary in nature, but nevertheless natural and absolutely necessary.

Klara Kristalova: Turning Into Stone runs through March 29 at the Norton Museum of Art. Admission: $12 adults; $5 students. Hours: 10 am-5 pm Tuesdays-Saturdays except Thursday, 10 am-9 pm; 11 am-5 pm Sundays; closed Mondays. For more information, call 561-832-5196 or visit www.norton.org.