Two strangers in a museum find themselves sharing the same opinion about that thing facing them. They call it “thing” because they don’t know what it is. And the brave one’s loud comment (“What the heck is this?”) is the shy one’s relief.

Such a flow of communication might be common at the Now WHAT? show, which opened recently at the Norton Museum in West Palm Beach in an attempt to bring to town a flame or two of the fire set in Miami Beach by this year’s Art Basel.

Out of that fair came the 31 pieces and 21 artists that compose Now WHAT? The selections were made by two of the museum’s curators, who went south to pick the freshest, riskiest, most relevant art representative of our times. They then decided that the theme bringing it all together will be communication.

In that sense, and only in that sense, the Norton show is great. Nothing gets a conversation going like a piece that makes no sense. That conversation usually goes something like this: Is this art? Here it is provoked by plenty, such as Pigeon Holes, by Roxy Paine, in which plasters of paints appear inside plexiglas like dead insects pinned down waiting to be examined.

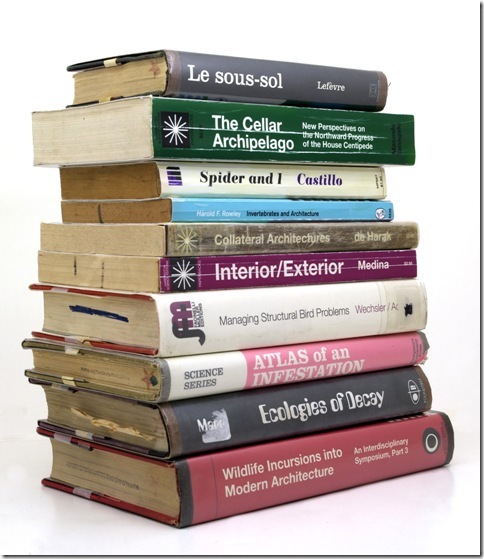

In Volumes from an Imagined Intellectual History of Animals, Architecture and Man, nothing was actually created, unless you consider the title of the piece or the order in which the books are placed a creative result. The work, by Julian Montague, consists of 10 old books, most of which have the image of a bug on the cover and hint at the effect small animals can have in the life of man.

Meanwhile with September 2010, Receipts, a 24-foot long strip of personal expenses, the artist, David Shapiro, is telling us that we are all artists. After all, as an observer pointed out, we all have collections just like this at home. Due bills? Receipts? Anyone?

One singular instant in which this dialogue ceases to be sarcastic comes courtesy of Bryan Drury and is titled Ali. It is a striking small portrait that calls us no matter where we stand in the room and made dramatic by its bright red background.

Once directly facing it, we marvel at how realistic and alive Ali is. Notice the pores of the skin, the imperfect flesh, the swollen lips and you will see condensed in this seemingly traditional/safe work the prints of a skillful artist.

Whenever I’m reviewing a show, I usually go alone. This time, however, I brought along company on purpose. I wanted to see if I’m alone in thinking that lately the concepts of simplicity and absence are being repeatedly presented as art. I saw it at Art Basel. It is here again.

A dark silver wood panel is all that Teresita Fernandez’s Nocturnal (Rise and Fall) is. Hers is the second piece to the right once you enter the gallery room. I can’t detect specific figures or a message. As it often happens with art, there is no explanation for it. All it seems to be is precisely what it is: solid graphite and pencil on wood panels.

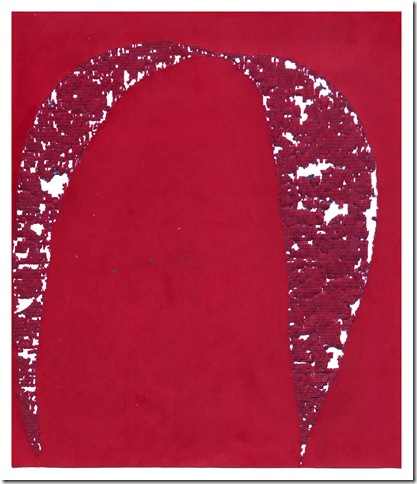

In Allyson Strafella’s foundation (2005) and inverted red catenary (2010) art seems to take the form of holes resulted from typing underlines and colons over and over on carbon paper.

When it’s not holes, art here is vanishing, disappearing, hardly visible, almost a ghost. No other work here puts it better than Christopher Russell’s Ghost-Ship-Wreck, an 18-frame piece done mostly in silver. Thin and thick white lines give life to the ship, which in some frames appears sinking and in others marching ahead.

Could it be that artists are teaching themselves to create less or use less to create? Is the trendy minimalism wave to blame?

I don’t know that you can simplify art without affecting its very essence. A kitchen, for instance, has two factors that make it identifiable: appearance and use. Simplify or alter its look as you may and you would still be able to tell it’s a kitchen through the way it is used. Art is not an appliance or a closet. It has no use through which it can make itself present or known. It relies on what you can see to make itself identifiable, ideally, as art.

Simplify the only thing it is and you end up with less of what it is, or even worse, you end up with nothing: a thing forced to pose for an audience when really all it wants is to be put out of its misery.

Kim Rugg’s The Story Is One Sign seems to me an example of this. If we go along with her message, the story is sometimes a dollar sign, $, and other times a “J” or a “K.” The artist has grabbed a front page of The New York Times and placed the same 30 times next to one another. In each copy, the content and images have been stripped from the page only to leave a sign or a letter. On one page, we can only see the “Ks” as they appeared originally on the newsprint. The rest, most of it, is white. Nothing to be seen. Less to judge.

By the end of the show my guest and I had reached a conclusion: The artists here had great concepts, ideas, but either got lazy halfway into their projects or they didn’t have much imagination to carry their creations to the very end. Or maybe, they simply didn’t care.

Or you could say that present here are great conceptualists or philosophers, but not necessarily great artists. Unless you find yourself already in the museum, this is not something you need to see. If you don’t come, you won’t miss anything.

The show was intended to be full of delightful surprises. And Now WHAT? seems like something we would say to the person who keeps interrupting us in the middle of something delightful. But that’s not what I feel like saying.

I want to be interrupted, pulled aside and told the secret behind this exhibit: Is it art or is it a joke? And to the museum curators I want to ask: Why? How? I get a feeling those visitors who do come from now until March 13 will be asking the same.

Now WHAT? runs through March 13 at the Norton Museum of Art. Admission: $12, adults; $5 ages 13-21. Hours: 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesdays through Saturdays; 1 p.m. to 5 p.m. Sundays; closed Mondays. Call 832-5196 or visit www.norton.org.