By Chloe Elder

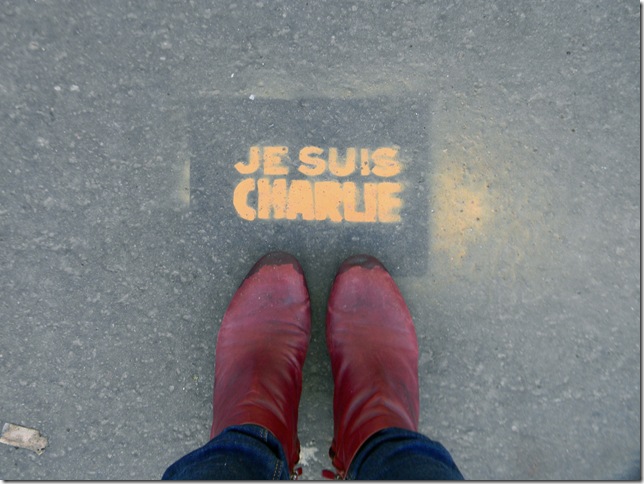

In the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attacks, the spirit of solidarity pervades Paris, and the evidence is everywhere.

Riding the Métro on the day after the magazine attack, I whipped my head around to see “Je Suis Charlie” written in large spray-painted letters on the walls of the Concorde station. And I continue to see the motto across the city, written on the streets, in shop windows, and hanging in banners from the Hôtel de Ville.

On Jan. 11, a unity march was organized in honor of the victims, which many world leaders attended along with approximately 4 million Parisians. The march flooded the streets that day.

“When we descended my stairs, we found even our tiny medieval street, which leads essentially nowhere, completely full of people,” explains Marc Kaadi, 30.

Kaadi, originally from Portland, Ore., moved to Paris this summer to marry his French husband. They live in the 3rd arrondissement, just a 10-minute walk from the Place de la République, the heart of the vigil and unity march.

“Everywhere we went, every tiny little side street, café, bar, store, bakery … all totally past capacity. The occasional car we saw essentially gave up on trying to move.”

Though Kaadi and his husband were unable to make their way to the official march, the people in the surrounding streets showed just as much enthusiasm.

“The whole parade, including my husband, started to sing the national anthem in unison. It was an enormously emotional moment, but I have to be honest: it was sort of cute, too. I wish I could have sung along.”

My own experience of the attack that has dominated the news for the past week or so has come to me the way it did to many millennials: through Facebook. But unlike the friend who had posted the news, I was in Paris. I was sitting in a café on Avenue Bosquet at around 1 in the afternoon when I learned what happened.

Immediately, I verified what I knew with news reports online. I found the address of the magazine’s headquarters and saw that I was far enough from the massacre to give me peace of mind. I live in the 7th arrondissement, near the Eiffel Tower, and this attack was in the 11th, farther west — a good half-hour commute.

Coincidentally, I had chosen a prime location to observe reactions to the attack. The café is a regular workspace for French and expats alike. The workers are bilingual, and many of the clients are American, or at least Anglophone.

One couple had come in on what I overheard was their last day in Paris. During their lunch, the young woman received a call from what I assume is her mother. The phone was on speaker, and I could hear a frantic voice saying, “There’s been a terrorist attack in Paris. Are you all right? Where are you?” I would later think how unlucky this couple was for choosing that day, of all days, to fly home.

(Two days later would be even worse, when the Charles de Gaulle Airport closed two of its runways amid a helicopter search for the two gunmen who had taken hostages at a kosher market nearby.)

I received my own fair share of concerned messages that week: from my sister, her boyfriend, my parents, a friend, another friend, my other sister, colleagues, and the editor-in-chief of this paper — all concerned for my safety.

For me and many other Parisians, however, it was a normal day. Aside from the influx of messages, and perhaps a few extra personnel in the Métro, it was Paris as usual.

“It didn’t change my life at all,” says Arthur Lamoot, 24, a French bartender at Diner Bedford (a.k.a “The Diner”) in the 7th arrondissement. He explained that unless you lived in an area that had been targeted by the group, you could spend your day without noticing what was going on.

Lamoot did not attend the vigil that night, and neither did I (as a general rule, I avoid situations that involve large crowds). Where I was, in fact, most confronted with the events of that week was not in Paris, but online.

Scores of Facebook friends posted, and continue to post, their opinions on Islam, terrorism, solidarity, and freedom of speech. News articles and videos were shared, and lively debates were held in the comment section. People sent their love and prayers to the city. And everyone “is Charlie” in solidarity.

“It’s become trendy,” Lamoot adds. Even a high-end clothing store, Gerard Darel, currently features “Je Suis Charlie” on its shopping bags.

The magazine itself has received an enormous amount of support, along with new subscribers. On Jan. 14, exactly a week after the first attack, Charlie Hebdo released its newest issue. People lined up in the early morning at kiosks around the city.

The paper sold out by 10 a.m., and the magazine announced they would issue more in the coming days. The special edition, featuring the Prophet Muhammad on the cover, is even being sold on eBay for amounts as large as $117,000.

The windows at the headquarters of the international news agency Agence France-Presse are covered in individual “Je Suis Charlie” signs, and police now guard the entrance, noticeably armed.

I kept my eyes on my computer screen over the next few days, watching the coverage of another murder, a hostage situation, and then another, until it all ended.

This past weekend I went to Brussels, a city to be announced as a suspected target for extremist Islamic attacks, and a city on high alert. Belgium deployed 300 troops in Brussels and other cities to guard against a future attack. (An anti-terror raid had left two dead and more arrested in the eastern city of Verviers on Jan. 16.)

My sister, 30, and her husband, 31, both living in Miami, had planned a trip over months ago, and invited me along before the word “terrorism” was on the news in Europe.

“Of all cities…” my sister jokes in response to all of the news reports. But if they had known before booking flights, would they have changed their destinations? They both shake their heads dismissively, and the conversation turns to food.

And they had no reason to be worried. Brussels, too, seems normal — well, as normal as a city covered in chocolate, waffles, fries, and thousands of types of beer can be. If we were being guarded by hundreds of soldiers, they were doing so subtly.

Chloe Elder lives in Paris, where she graduated from The American University of Paris in 2014. She does research for The Letters of Samuel Beckett, is the copy editor for The Bohemian, and is an editorial assistant for the international journal Music & Literature.