By Chloe Elder

In 21st-century society, the onetime symbol of Paris, the flâneur, is nearly extinct. In its native city, the numbers are dangerously low. Conservation efforts have done little to protect those who remain in the wild and all attempts to breed in captivity have been futile. And awkward.

The flâneur is one who strolls, wanders, and traverses the city streets with no aim other than to keep moving and to see more. A flâneur knows that a leisurely promenade after dinner is the true dessert in any meal. And the flâneur is as essential to Parisian city planning as the Haussmannian streets. He is an active participant in observation and understanding of city life, one who delights at being in “the center of the world, and yet remain hidden from the world,” as Charles Baudelaire, 19th-century poet and flâneur extraordinaire, once put it.

These days, however, the typical pedestrian Parisian is seen pushing through and bustling by — digesting nothing but the view of scuffed shoes on the pavement.

There are still some, however, who aim to preserve their dwindling race by upholding the strict standards of strolling that once proved them to be a mighty, if easily overlooked, population.

One of those who still savor each step on the way to nowhere in particular is a kind of tourist. Not the tourist who schedules every baguette, café, and musée, being sure to snap at least 30 pictures of the Mona Lisa, but the tourist who simply wants to see the city — and if he just happens to find himself in front of Rodin’s Le Penseur, then all the better. This is the type of person who has a permanent grin on his face, as if constantly questioning his luck to be in such a beautiful place.

The second living flâneur is similar to this lucky tourist, with the exception of one detail: residency. This person has lived in the city for a few years and usually could not care less if she’s standing on the Métro platform or at Place Vendôme. But there are some days— some days, when she finds herself on a small street where she cannot help but notice the sound her heeled boots make on the cobblestones, or the smell of fresh bread wafting from a nearby boulangerie. Oh, she may think skeptically, “must be manufactured.” But she helplessly falls in to being a flâneuse once again, as she was when she roamed the streets alone for the first time.

The third type is a true flâneur, because he was never anything else. He’s older and knows the streets well — neither cobblestones nor Rodin can surprise him — but he also hasn’t forgotten how beautiful they are. Not even for a second. The city envelops him as it did the gentlemen of the 19th century and allows him access to the secret wonders of Paris that were always there and will always be there for those who take the time to look.

Heather Hartley, an American writer and poet in Paris, is one who is always taking the time to look — and then write about it. Aside from her work as an editor and writer for Tin House magazine, Hartley has also recently been teaching flânerie and writing to American high school students who have come to the city to study arts in the summer, a noble effort for Parisian flâneur repopulation.

Heather Hartley, an American writer and poet in Paris, is one who is always taking the time to look — and then write about it. Aside from her work as an editor and writer for Tin House magazine, Hartley has also recently been teaching flânerie and writing to American high school students who have come to the city to study arts in the summer, a noble effort for Parisian flâneur repopulation.

“There are such rich traditions of wandering and writing in Paris that taking part in this tradition that has been explored for centuries in so many forms of writing seemed like it could be a direct and immediate way to encourage students — or anyone — to find the impetus to write,” says Hartley.

Hartley is also a wandering writer herself and her “walking sonnets” feature in her forthcoming collection, Adult Swim (published by Carnegie Mellon University Press). I had the pleasure of hearing some of these urban poems at a panel held at The American University of Paris in March. Though the reading was held inside the school, listeners were transported from the Left Bank to the Right, through the streets and jardins, following in her footsteps with every spoken syllable.

Hartley believes the spirit of flânerie is alive today, “and it’s so easy to take part in it.”

“Walk outside and start walking,” she says. “And sometimes the best way to discover the city is without a specific path, to let the city lead you.”

She urges any novice explorer to experiment with flânerie. All you need is a notebook, pen, and some money for coffee or tea. Then, let the city of Paris — or any city — reveal itself.

“The city can be like a vibrant, living book to be read and re-read — and enjoyed,” says Hartley. “And with a comfortable pair of shoes, you can literally and figuratively go very far.”

So, I decided to take her advice, though I must admit I felt like a bit of a skeptic. I was unsure how to “just walk” without some sort of destination, since walking is usually just another mode of transportation for me. Having read and re-read the “book” of Paris quite a few times already, I thought I should skip to my favorite chapters. So, I cheated: I would take the bus to an area I knew was pretty (the 6th and 5th arrondissements) and then from there walk back to my apartment.

But to my surprise, Paris had other plans.

Whether it was the spirit of flânerie or just an American urge to shop, I cannot say, but a cool looking “kilo shop” had me jump off the bus three stops early. (A “kilo shop” is a thrift store where the clothes are priced by weight.) I left the store only to notice a busy looking area across the street. I made my way over through a small section of piétons (pedestrian roads) filled with cafés, cheese shops, and street music.

From then on, I need not think twice about any decision, for the flâneuse in me took over. Of course, I should stop to pick up a macaron (or two) if I happen to see such a shop down the way — Pas de question! I asked the vendeur about the light green one labeled “bergamote,” to which, upon hearing my accent, he responded, “Earl Grey tea” in English. Intrigued, I bought one and another (this time, blueberry-flavored) in case the first disappointed my taste buds. It did not.

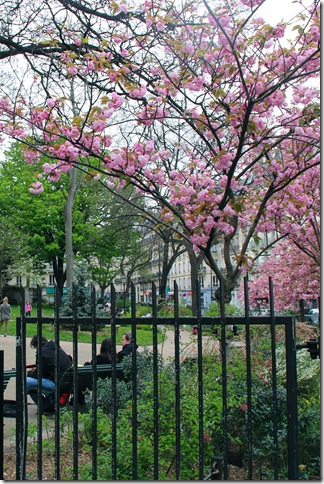

The sweet sustenance then powered my promenade along cobblestones and crosswalks throughout the 5th and 6th arrondissments, until sights of cherry blossoms in the distance brought me to a park I never knew existed. Framed by an ivy-covered wall of the former École Polytechnique and a line of the lavender-colored trees, I finally found myself at Square Paul-Langevin.

The city was truly guiding me, showing the way with a glimpse of color or an overheard note of music, despite my intent to be only a faux-flâneuse. And once I had embraced my destination of “anywhere and everywhere,” I found it easy to be led.

I was particularly inspired by the petites rues, the smaller the better. I was glad to find one such street after a few splotches of “street art” beckoned me to its start. The width was barely the size of one smart car, and I strolled through it dead center. Walking down and looking up, I noticed the beautifully uneven lines. One building would bulge into the street just a pinch more than the one before and then recede again with the next. And although the overall direction was straight, the pavement curved a bit here and a then little bit over there. The crookedness wasn’t something you would notice in a hurry, but did make me think that these sorts of little imperfections were what make lovely little streets even lovelier.

Then, the little street, seemingly hidden from the world, would open up onto a busy avenue filled with the masses of Paris. I was then drawn into the crowds. For a few blocks I couldn’t help but eavesdrop on the conversation behind me, if it could be called a “conversation.” The man speaking seemed so passionate about his subject that he could barely get a sentence out. He would start, “Et, le…le…le…le…” find the noun and then continue, “de…de…de…le…” I chuckled and felt a bit sorry for his interlocutor, who could not simply walk away, as I picked up my pace down the road.

Later, I was wandering in the 5th arrondissement, where Roman Paris, or Lutetia, used to lie. Behind the Musée Cluny, the museum of the Middle Ages and Cluny thermal baths and mansion, a knot of tourists caught my eye. They had swarmed a particular statue just outside the museum. I crossed the street to investigate this bronze mystery man to find Italian teens rubbing the well-worn foot of Michel de Montaigne. (I assume rubbing his foot is good luck, but I couldn’t quite discern from the Italian.)

At the end of ma petite aventure, I settled at a corner café for an espresso before heading home. I would take the Métro, but while my feet may have been tired, my mind was wide awake to the wonders of wandering.

And the effects of my flânerie have yet to wear off. Walking my usual way home, I noticed a small courtyard with a beautiful tree and thought, “Well, when did that get here?” but made myself a promise to look at it from now on every time I pass.

And even now, sitting on my couch writing this piece, a glance out the window shows a tabby cat sitting precariously on a 4th-floor ledge in front of a billowing white curtain until we both retreat from our respective windows, presumably for a little nap.

Chloe Elder, a graduate of the Dreyfoos School of the Arts, is a student at The American University of Paris.