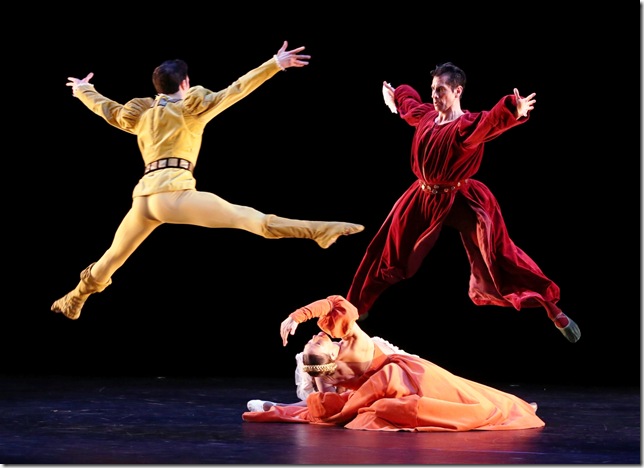

A scene from the Limón Dance Company’s The Moor’s Pavane. (Photo by Bill Hebert)

By Tara Mitton Catao

While out on its 70th anniversary national tour, the Limón Dance Company made a stop here in South Florida as part of the Duncan Theatre’s Modern Dance Series.

The program celebrated the creative essence of its founder/creator José Limón and gave us the opportunity to see three of his masterworks spanning a period of 60 years. Under the caring hand of longtime Artistic Director (and former dancer in the company) Carla Maxwell, the dedicated dancers of the troupe lovingly breathed life into each of the works presented.

Limón had a deep interest in expressing human emotion through movement, and in order to convey this, he used strong and dramatic gestures in combination with the rising and falling movement of the chest (breath). The use of breath was a motivational source for Limón’s lush and nuanced movement and in his choreography, there was a constant relationship to earth — of weight and falling (exhaling) and weightlessness and rebounding (inhaling).

The Moor’s Pavane, an abridged version of William Shakespeare’s Othello, is Limón’s most celebrated work. Created in 1949, it is considered a modern dance classic but it has mostly been seen performed by ballet companies. Principal dancers the world over (including such superstars as Rudolf Nureyev) have assumed the different theatrical roles in the work.

Limón’s version of the central drama in Othello unfolded within the form of a Renaissance court dance — the pavane. Amidst the courtly arm gestures and promenades, there was a certain cinematic richness as The Moor (Francisco Ruvalcaba), dressed in a long dark red velvet tunic, succumbed to an evil plot hatched by His Friend (Ross Katen) to dishonor The Moor’s Wife (Roxane D’Orléans Juste). Aided by His Friend’s Wife (Kathryn Alter), dressed in a heavy burnt-orange velvet gown, the intrigues fractured the formal court dancing as the human interactions escalated. Limón’s elegant theatrical gestures built in intensity until Othello’s unfounded rage resulted in the tragic murder of Desdemona.

It was quite a different experience to watch the Limón Dance Company (rather than a ballet company) perform The Moor’s Pavane. The different training of the dancers naturally brought a different look to the work. Friday night, it was filled wonderfully weighted movement that was full of breath and suspension, with much less emphasis on the legs, feet and the rigid posture to which ballet dancers adhere.

A scene from the Limón Dance Company’s Mazurkas. (Photo by Bill Hebert)

The technical expertise of the company dancers was delicately and expertly honed in Mazurkas, a work that Limón created after visiting Poland at the end of World War II to reflect the “triumphant spirit” of its people. Choreographed to a variety of pieces written by Frédéric Chopin, Mazurkas was a stunning example of the multitude of variables in the Limón technique and the forerunner of the many Chopin piano ballets that followed.

Unlike most of Limón’s choreography, which is more theatrical, this work was light, understated and full of delightful, delicate nuances in every moment of movement. Working with just a small selection of movement vocabulary, which was constantly being re-explored and redefined, the dancers presented a series of solos, duets and small to larger ensemble sections with great subtlety and artistry.

The engaging 3/4 meter gave a wealth of opportunity for the performers to personalize their interpretation of the music. Limón felt that any part of the body could lead a movement and in this performance, all the dancers were wonderfully unique — initiating movement from different places in their bodies as they interpreted the music and shaded the choreography with dynamic depth and counterpoints.

This performance of Mazurkas (which was created in 1958) was refreshing to see as it was all about quality. There was no glitz, no tricks, no fanfare: all of which we see way too much of today. It was simply about the full development of the qualities within the movement. Each section just kept getting better.

In “Opus 17, No. 4,” Francisco Ruvalcaba’s beautiful upward sternum arc and his downward reach to touch the earth articulated Limón’s fascination with fall and recovery. A very special interpretation was seen in the solo “Posthumous in A Minor,” Logan Frances Kruge showed an extraordinary awareness and sensitivity to dynamics. She was just marvelous, never stopping her luxuriant movement as she intricately overlapped her transitions from one to the next.

The seemingly utter simplicity of Brenna Monroe-Cook and Ross Katen’s duet danced to Chopin’s “Opus 30, No. 4” was a mirage. It was very multi-layered and delicately textured. The genuine focus between the two of them as — facing each other — they linked their arms and danced together, was so engaging. Their small lifts were like gentle embraces.

A scene from the Limón Dance Company’s The Winged.(Photo by Bill Hebert)

The rather long-winded close to the program was The Winged, a 40-minute work with 11 sections choreographed to a somewhat distracting score that was interspersed with sounds of bird cries and the wind. Originally it was an hour long and was to be performed in silence, but just before the premiere in 1966, Limón added snippets of incidental music and nature sounds. Artistic Director Carla Maxwell commissioned the present score by Jon Magnussen to replace the original sound score in 1995.

When it was first presented, it must have been powerful and original with its distinctive movements that suggested all things feathered and winged. The repeating movement vocabulary was not literal but abstracted and brought loose images of guarded interaction, confrontation, aggression and even cannibalism.

There was a pecking hand gesture to the top of the head while holding the ankle with the knee down that had a grooming aspect to it. In the “Feast of Harpies,” five women raised their legs in a front attitude in order to take a bite out of their shin. During the randomly animated parts, there was a great deal of quivering hands and feet and arms raised upwards like wings as they departed and reappeared.

In all three solos, the dancers’ performances were outstanding. In “Eros,” Katen showed a great command and strong commitment to these strange gestural movements. During the repeated phrase of rebounding up from the earth and suspending to do a bow-and-arrow gesture, it was uncanny but one could sense that the music was made after the movement had already been choreographed.

Monroe-Cook’s highly focused performance in “Sphinx” caught my wandering attention. She is an amazing and elegant dancer who very convincingly inhabited the peculiar movements and facial expression in her solo. She personified the mythical half-woman/half-lion with the wings of an eagle who perched on a rock waiting for travelers to try to unsuccessfully solve her riddles before she devoured them.

Mark Willis, who is in his first year with the company, had the same purposefulness in his dynamic solo “Pegasus,” but it had a very different look as it was molded by his raw energy and sinewy technique.