Every season, South Florida gets visited by touring big-name orchestras from northern climes worldwide that for some reason find this part of the country particularly urgent to see in February.

One of the benefits of our gentle weather is that we can see these major orchestras up close, but another less appreciated benefit for us local concertgoers is that these visits provide one of the few outlets — other than the New World and Cleveland orchestra Miami residencies — to hear a large symphony orchestra.

Canny residents of the Boca Raton environs have known about the conservatory orchestra at Lynn University for years and packed its concerts, and that has provided them the opportunity to enjoy some extra sonic heft outside the normal round of chamber orchestra groups we’ve had since the demise of the Florida Philharmonic a dozen years ago.

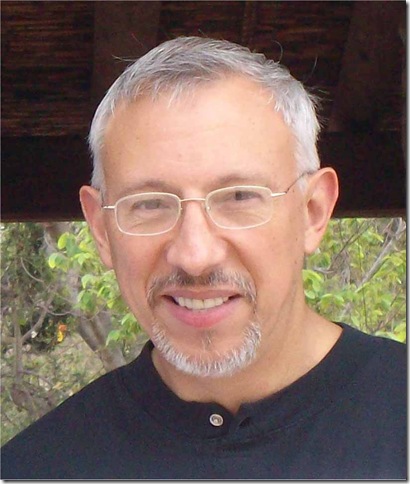

That student orchestra, the Lynn Philharmonia, has now reached an entirely new level of excellence, as last weekend’s concerts at the Wold Performing Arts Center amply demonstrated. This is due to two things above all: A growing reputation for musical training that is luring a more accomplished level of student, and even more crucially, the leadership of conductor Guillermo Figueroa, a first-class violinist whose revised rehearsal regime and command of the repertoire have translated into some very impressive music-making.

Last Sunday’s concert introduced the theme of this season, which is music based on works of literature. And the first piece out of the box was an orchestral tour de force: Richard Strauss’s tone poem Don Quixote (Op. 35). Like all of his 1890s-era symphonic poems, Strauss’s Quixote is a massive, sprawling work that demands virtuoso-level playing from each section of the orchestra and an attention to structural detail that allows disparate sections to cohere in narrative fashion.

Matters are helped somewhat in this piece by the well-known scenes from Cervantes’s epic 17th-century novel of the Knight of the Woeful Countenance that Strauss has chosen to depict by embedding them in a giant theme and variations (illustrations by Gustave Doré and Honoré Daumier were projected behind the orchestra during the performance). It is also in some ways a mini-cello concerto, and for this performance the soloist was Lynn professor David Cole, a longtime member of the faculty and a frequently encountered performer in tandem with his wife, violinist Carol Cole. An almost equally prominent part is given to a solo viola, here performed by Lynn master’s student Brenton Caldwell.

With the exception of a few seconds of imprecision in the opening bars, this was a hugely impressive reading of this piece. Nothing in this monstrously difficult score seemed to daunt the 80-plus players on stage, who brought it off with all of the elements we look for in Strauss: brilliant colors, high drama, deep sensuousness, and a sense of extravagance that is all the more compelling for being so tightly reined in. The orchestral soloists were uniformly good, beginning with the concertmaster, who played his numerous utterances with accuracy, intensity and flair. The clarinetist, whose rising and falling arpeggio is a central motif, had a big, luscious sound even in the higher registers; equally fine were the principal oboist and flutist, and the euphonium and bass clarinet duettists.

But the biggest change here from previous seasons of the Philharmonia was the brass section, which this year is at last the equal of its wind, string and percussion colleagues. There were none of the intonation problems of concerts past, and from the very outset it was clear that one was not going to have to worry about whether their entrances would be iffy or not. Here was a brass section that fulfilled the promise of the writing rather than struggled to come to terms with it, and it was enormously gratifying after many years of Philharmonia concerts to hear this aspect of the group finally come together.

Cellist Cole was very fine, with a strong, forceful tone and vigorous attack that brought out Quixote’s bumptiousness and mania persuasively. He has a dark, penetrating sound that commands attention, and a masterful technique that allows him to bring out all the moods of this part most capably. Caldwell, the Sancho Panza to Cole’s Quixote, also was excellent, with a fluid command of the fingerboard and an attractive, memorable sound.

Figueroa’s reading of the tone poem was somewhat on the rough-and-ready side, and he tended to push things like the famously dissonant flock of flutter-tonguing brass sheep a little bit out of context, but this occasional lack of subtlety is surely due more to the fact that the students had only been together a short time before having to perform for a paying audience. And overall, he did a splendid job of keeping the music hanging together, when it can so easily go off the rails.

The second half of Sunday’s concert was much shorter, and featured two works, the first of which was the second suite from Manuel de Falla’s music for the ballet El Sombrero de Tres Picos (The Three-Cornered Hat), based on Pedro de Alarcón’s short story of an amorous old man who tries to seduce the pretty young wife of a miller. Falla, with Victoria the finest of all Spanish composers, created in this ballet a score whose popularity has remained undimmed for a century, and the Philharmonia performance reminded us why.

Figueroa led this piece, as he often does, from memory, and it was clear that his knowledge of the work helped give the performance such assurance. This was most evident in the second-movement “Miller’s Dance,” which had very effective dynamics, especially the decrescendo after the first full string rhythms, and a wonderful lightness of touch that made the music come vividly to life. The English horn player was especially good, and the closing Jota had terrific high spirits without being too heavy.

The contemporary Uruguayan-born American composer Miguel de Aguila supplied the final work, an orchestral showpiece called Conga. It’s based, as Aguila told the audience, on a bizarre dream about a Dantean conga line in hell, and it’s great fun. A hodgepodge of insistent rhythm, exuberant orchestration — including a big-band fragment led by a well-played, screaming high trumpet part — and a growing sense of approaching implosion, it makes the most of its 5 minutes. The Philharmonia students played it with precision, power and engaging style, joined by Aguila in the orchestral piano part.

If your other obligations keep you away from some of the guest orchestras this season and you want to hear a full-size group, the Lynn Philharmonia has reached a level that will make it well worth your while to attend. With Miami Beach’s New World Symphony down south, the Philharmonia allows concertgoers to get an encouraging look at the kind of talent that is stepping up to continue the American orchestral tradition, and if the programs are as good as this one was, it gives them much more than that.

The Lynn Philharmonia plays its next concerts on Saturday, Oct. 24, and Sunday, Oct. 25, at the Wold Performing Arts Center on Lynn’s Boca Raton campus. Tchaikovsky’s Francesca da Rimini shares the bill with Beethoven’s Eighth Symphony and the Intermezzo from Puccini’s opera Manon Lescaut. Tickets: $35-$50; call 237-9000 or visit events.lynn.edu.