It’s hard to know whether a change as simple as a rehearsal strategy can make all the difference in the world for a performing organization, but in the case of the Lynn Philharmonia, this much can be said:

Its opening program this past weekend was easily the finest opening concert of the season the conservatory orchestra has ever given, and in its freshness, maturity and achievement it marked a new day for the Boca Raton university’s program. It was not far shy of the standard usually achieved by the New World Symphony of Miami Beach, and it means area audiences are the lucky beneficiaries of a much improved orchestral environment for the 2014-15 season.

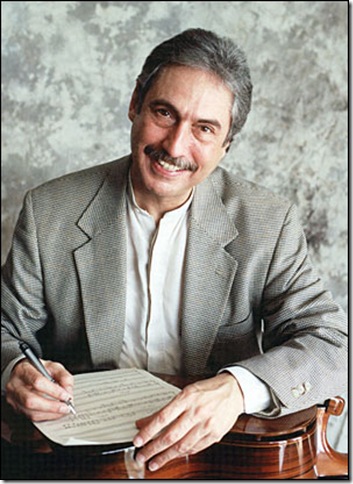

The credit surely has to go to its director, Guillermo Figueroa, a first-rate violinist and fine conductor who sat in the concertmaster’s chair for the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra and directed the New Mexico Symphony until it folded a couple years ago. Figueroa, besides giving through his own musicianship and career something for his students to shoot for, has changed the rehearsal schedule so that the sections of the orchestra meet the week before the program, and the whole group does a read-through before coming back for the week of rehearsal before the two weekend concerts.

Those are the most likely reasons for the sheer excellence on display Sunday afternoon at the Wold Performing Arts Center, which even this early in the season drew a three-quarters-full house. Figueroa opened with his own compilation of two concerti for violin and strings by the contemporary Puerto Rican composer Ernesto Cordero, Ínsula and Concertino Tropical. The four-movement mix-and-match, dubbed Ínsula Tropical, featured two movements from the 1998 concertino as its outer movements, and two from the 2007 Ínsula in the center.

From the opening notes, it was clear that this was going to be a concert at a much higher level than many of the Philharmonia’s past concerts. The string players rattled off the little 16th-note shudder in the opening bars of the concerto with exemplary precision, and soon after the violas showed their depth with a sinuous soli of dark beauty.

Figueroa, standing center stage with the strings arrayed in a half-circle around him, played splendidly, with an ease and mastery that was delightful to watch and hear. He knows every note of these pieces and brought out every bar of their virtuosic challenges spotlessly. Even the showy portamenti of the first movement were carefully judged and entirely musical, when he could forgivably have milked them for audience appeal.

Cordero’s music poses no difficulties from the standpoint of language, it being thoroughly conservative, tonal, attractive and suffused with a winning Latin flavor. In the second movement, “Jajome,” Figueroa demonstrated his ability to play the balladeer, playing the gentle waltz theme with great tenderness and communicative power. Ensemble remained rock-solid in the tricky third movement, “Fantasie salsera,” and the concerto finished with a thrilling race to the finish in “El colibri dorado,” a 90-second speed-trial romp that ended with bow flourishes from one and all and shouts of approval from the house.

Figueroa called Cordero, who was in the audience, up to the stage for a warm curtain call, and then played, as a gift for him, a solo version of a Piazzolla tango, a difficult and showy tour de force that showed again that he is an instrumentalist at the top of his game.

The full orchestra then came on stage for a relative rarity, the early Cockaigne Overture (Op. 40) of Edward Elgar, a composer who gloried in the heft and gleam of a big late-Romantic orchestra. From the outset, the orchestra was fully in Elgar’s quirky world, playing with gusto and bigness and all the requisite cheekiness this music requires.

Like his contemporary Richard Strauss, Elgar wrote for virtuoso orchestras, and the leaps and skyrockets of this overture’s opening theme were played with admirable accuracy by the strings, and indeed throughout the work, the strings played with expert ensemble. What was particularly good here was the wind and brass work, which is so critical to Elgar’s sound world. The brasses in particular were far better than previous incarnations of this orchestra, and only some occasional sectional intonation flatness in the unison passages kept this performance from being ideal. But that was actually a small price to pay for hearing trumpets, horns, trombones and tuba playing so confidently and so well overall.

This was an Elgar that snapped, swaggered and rollicked, with the right kind of bumptious high spirits that makes this piece such fun. It was a thoroughgoing pleasure to hear, and a good way to end the first half.

The second half was devoted to the Fourth Symphony (in E minor, Op. 98) of Johannes Brahms, the last of his symphonies and in some ways his most challenging. It received a gratifyingly powerful, intense reading by these students, a reading that was completely Brahmsian and yet also lighter on its feet than some more traditionally oriented performances.

The first movement’s opening theme was lush but supported by a cushion of air that let it float rather than sink; Figueroa’s tempo was just right, and made the music move along without diminishing its gravity. The woodwind work throughout the symphony was very fine, and all of the principal players for the Sunday received extra applause at the curtain.

The second movement, too, had a tempo that kept things moving, and while there was a slight intonation difficulty in the opening horn call, here was where the winds found their independence, playing beautifully off the strings in floating, evanescent lines, with fine work from flute, clarinet, oboe and bassoon. The scherzo was equally good, with plenty of fire, a swift pace and good brass and percussion work.

Figueroa also did estimable work in the finale, which is notoriously difficult to get across because its stripped-down, serious layout can make it hard to follow. But the Philharmonia did well, with fine playing from all sections and a tense, somber coloring that lent the music an extra urgency.

The usual first concert of the Philharmonia season is the warmup concert, with new students feeling their way and getting used to the idea of performing as an ensemble. But this past Sunday’s concert sounded in no sense like a warmup, and it raises not only audience expectations but standards overall that will be not easy to better. For the Lynn Philharmonia, there is the Before Figueroa era and the Figueroa Era, and if the concerts remain this good for the whole season, their leader may end up doing much more for this school and their careers than anyone could have hoped.

The Lynn Philharmonia’s next scheduled concerts are set for Oct. 26 and 27 at the Wold Performing Arts Center. Three student clarinetists will be tasked with an individual movement of Harold Farberman’s concerto Triple Play, and Guillermo Figueroa will lead the orchestra in the overture to Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail and the Rachmaninov Second Symphony. 7:30 pm Saturday; 4 pm Sunday. Tickets: $35-$50. Call 237-9000 or visit events.lynn.edu.