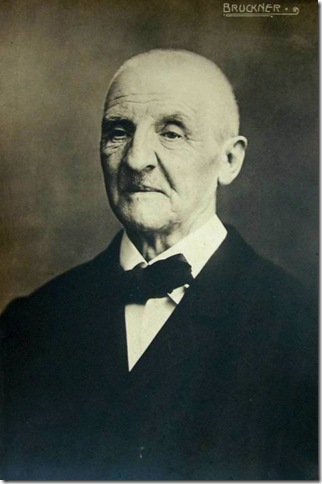

The Fourth Symphony of Anton Bruckner, subtitled Romantic, conveys the ecstatic, uncompromising intensity the composer strove to achieve in his lifetime, using a new way of developing the symphonic form.

Palm Beach Symphony director Ramon Tebar led his 70-piece orchestra through a thrilling performance of this symphony Monday night at the DeSantis Family Chapel, transforming himself from a talented and gifted conductor into a much higher category of musician; only someone with exceptional prowess could draw such excellent playing from an orchestra that normally tackles chamber orchestra music using 40 players.

The program, titled “Music of the Future,” was designed to show how Richard Wagner and his disciple, Bruckner, applied a unified creative statement using massive forces. From the 1850s on, debate raged between Wagner and Viennese critic Eduard Hanslick, who openly disliked Wagner’s radical new concepts of composition. So the evening’s warm-up to Bruckner’s Fourth began with three of Wagner’s “chestnuts,” as Sir Thomas Beecham liked to say.

First came the overture to Wagner’s opera The Flying Dutchman. Creating all the sounds one associates with rough seas, it begins loudly using all the orchestra. A calm passage follows, led by lovely oboe and wind playing interrupted by a theme from the French horns — more raging seas — using the timpani very effectively. The strings were superb as they built to the main operatic tune sung by Erik, Senta’s lover, followed by a great crescendo and peaceful seas at the last.

Let me take a moment to observe the improvements made in the DeSantis Chapel for this concert. An apron stage extension from left to right was added to seat all the first-desk string players, who were stage right, and the viola section, stage left, thus thrusting the stage forward. In the past, the east end apse would trap the sound. Also, as if by magic, the old reverberation seems to have disappeared by using curtains to line the apse’s walls.

The prelude to Act I of Wagner’s Lohengrin opened with a beautiful string introduction warmly joined by quiet brass and woodwinds. The violas play a passionate melody as the brass, in Wagnerian fashion, begins to swell. The strings descend into a sublime reverie — a motif the composer used to signify the discovery of the Holy Grail, or communion chalice. It ends so reverently with muted strings; one could have heard a pin drop.

The final Wagner selection, the Prelude and Liebestod from Tristan und Isolde, begins a haunting introduction by the cellos and woodwinds, who played wonderfully well. The horns pick up the yearning theme as the orchestral exposition takes shape, at which moment this ensemble sounded beautifully balanced in every section. Marvelous crescendos, stunning played, bring the Liebestod to a close. Nobody wanted to break the silence with applause, so inspiringly was this lovely music rendered.

After intermission, it was time for Bruckner. I first heard Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony in 1948 with Sir John Barbirolli and the Hallé Orchestra. It required seven additional tubas, recruited from Foden’s Motor Works Brass Band. My appetite whetted for his music, I bought a recording of Bruckner’s Fourth in East Berlin in 1954 when travel between the four occupied sectors was possible. Vaclav Talich conducted the Czech Philharmonic on my Supraphon vinyl disc, which I still have. It is a magnificent work. I admit to having doubts the Palm Beach Symphony could pull it off.

A four-note tune on the horn (kudos to Marc Gelfo) laid over hushed shimmering strings opens the symphony. This tune repeats many times from movement to movement, building to what sounds like a medieval city coming to life, complete with church bells pealing. The long 20-minute first movement draws to a close with a throbbing orchestral melody as the solo horn dominates the atmosphere.

A sublime cello melody introduces the second movement. Tripping strings are punctuated by woodwinds and horns. Cellos repeat their original tune with variations accompanied by plucked strings that keep the momentum moving forward. The Scherzo has horns off in the distance, sounding like hunting horns that get nearer and nearer. Over the full orchestra they come in continually as the music builds to a huge crescendo.

One has to marvel at the originality of Bruckner’s orchestration with ascending strings, flutes, and a clarinet that plays a shepherd-like pastoral song that lilts along supported by very sweet strings. It has a breathtaking end that is touching in its majesty.

By now, the attentive 400 people in the audience must have been marveling at Tebar’s brilliant interpretation of the symphony as the last movement opens with a huge statement from the whole brass section. The superb strings answer in unison. The players showed no signs of tiredness as they played the music relentlessly, giving of their best.

Toward the end, reflective cellos are joined by a lone clarinet, rolling timpani and luscious excited strings to bring this magnificent work to a close. It’s the best performance I have ever heard from the Palm Beach Symphony. From the conductor on down, they were inspired.