Location, location, location. It’s the well-known rule of real estate, but it also applies to musical institutions of higher learning.

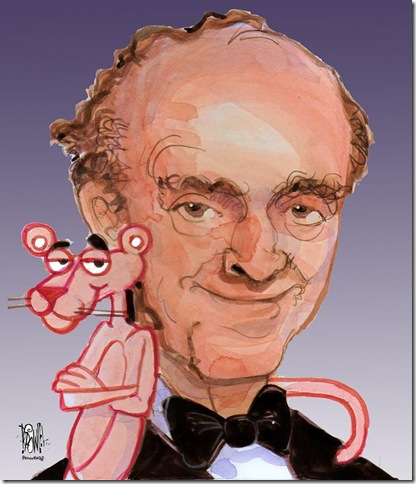

Witness the case of the Henry Mancini Institute. Founded by composer/conductor Jack Elliot in 1997 to honor its namesake Grammy-and-Oscar-winning composer (who died in 1994 of pancreatic cancer at age 70), the institute provided fully funded scholarships to more than 800 young musicians, plus hands-on educational programs to more than 30,000 students in Southern California schools, over the course of 10 years.

Yet the summer institute, based at the University of California at Los Angeles, ceased operations Dec. 31, 2006, citing the all-too-familiar bleak outlook for arts funding.

That bleak outlook continues, but so does the Henry Mancini Institute, now that it’s moved to South Florida.

The University of Miami has become the institute’s new home, and the Henry Mancini Institute Orchestra has already started fall semester performances through UM’s Frost School of Music. The school is building toward its goal of 65 HMI Fellowships by 2012, and already is more than halfway there.

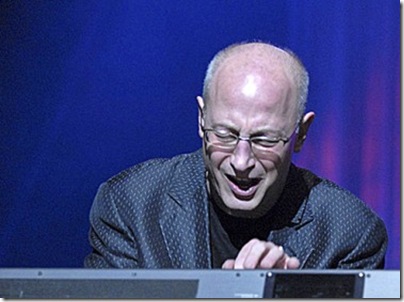

But was all of this because Miami’s economic climate is decidedly better than that of L.A.? No. The factor that overruled economics was indeed location, location, location — specifically the location of Shelly Berg, who succeeded the retiring Bill Hipp as dean of the Frost School of Music in 2007.

“I would say that it was a good foot in the door,” says Berg, who’d become familiar with the HMI while he was a professor and chair of jazz studies from 1991-2007 at another fine musical institution — the Thornton School of Music at the University of Southern California.

“I have a close relationship with the Mancini family. We’ve vacationed together, and I’ve performed and recorded with [jazz vocalist and daughter] Monica Mancini. So that relationship was a foundation. But I would also say that the family believed in what the University of Miami’s Frost School of Music already stood for, and also how I wanted to leverage that into a Mancini Institute presence. They believed in the vision that I had, and they’re excited to see that vision come to pass here.”

Ginny Mancini, Henry Mancini’s widow and a former vocalist with Mel Tormé’s “Mel-Tones,” agrees.

“There was a huge outcry from the arts community after the Mancini Institute’s demise,” she says. “The alumni, faculty, and patrons of the organization were all searching for answers as to how it could be saved. But I was inspired by the passion of Shelly Berg, and gave him my blessing to restart it in Miami.”

The Frost School of Music at UM certainly wasn’t the only suitor.

“The Manhattan School of Music, University of Utah, and the University of Southern California all wanted it,” Mrs. Mancini says. “But I trusted that Shelly would carry on with a reflection of who Henry was — the man, the musician, the writer, the teacher. Music without walls, categories and preconceptions is what the Henry Mancini Institute is all about. And I know that it’s in good hands with Shelly.”

Berg’s hands-on approach includes switching the HMI from a summer institute at UCLA to a full part of the curriculum at the Frost School of Music.

“As the dean, I felt that the school should be doing what the Mancini Institute was doing as a summer institute in L.A.,” he says. “I thought it should be embedded in what the school does year-round. One of the reasons I became dean here was that, whether or not we got the Mancini Institute, I intended to implement what it stood for.”

“The people who ran the institute saw that musicians were being trained in conservatories for a very narrow slice of the music world,” Berg continues. “And they felt that it was important to take some of the best people from conservatories and give them an experience where they worked with film composers, and world and jazz musicians, and looked at things like improvisation and entrepreneurship.

“They allowed people who were in the very best conservatories to take eight weeks in the summer and get this kind of perspective on music. But they were also essentially having to create a university from scratch every summer, which is a tremendously expensive undertaking. We already had that university in place.”

The Frost School of Music also now houses the HMI library, which features hundreds of orchestral pieces by Mancini and other composers.

“It’s fantastic,” Berg says. “There are not only all those pieces of orchestral music, but also a commensurate number of archival recordings of performances that the institute did in L.A., with some of the greatest musicians in the world. So for research, study and performances, it’s a treasure trove.”

Berg is a renowned pianist, composer, arranger and author as well as an educator. His self-titled jazz trio features Monica Mancini’s husband, drummer and producer Gregg Field. But if you think that the HMI relocated to Miami solely because of the Mancini family’s friendship with Berg, then you haven’t looked at the accomplishments he had leading up to that decision.

The 54-year-old Berg was born in Cleveland, coincidentally the hometown of Henry Mancini (who grew up in Pennsylvania), although the two never met. Berg’s father, trumpeter Jay Berg, inspired his son early enough so that, at age 6, he was accepted into the gifted program at the Cleveland Institute of Music. After the family had relocated to Houston, the young Berg turned down a job with Woody Herman’s Thundering Herd orchestra to continue his musical education.

His own career as an educator started when the University of Houston offered him a teaching fellowship. Berg also recorded with country star Mickey Gilley while in Texas, and his resume as a composer and arranger now includes work with artists as diverse as Kurt Elling, Bonnie Raitt, Elliott Smith, and KISS. He’s contributed to films (Men of Honor), television series (Dennis Miller Live), and has several ADDY awards for his commercial jingles.

Berg was also president of the International Association of Jazz Educators (IAJE) from 1996-1998, and has authored several acclaimed educational books. As a pianist, he really didn’t focus on jazz until 1988, when he made the finals of the Great American Jazz Piano Competition. But he’s played and recorded with Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, Buddy DeFranco, Tierney Sutton, Patti Austin, Bill Watrous, Ray Brown, John Clayton, Ed Thigpen, and Peter Erskine. The Shelly Berg Trio (with Field on drums and Chuck Berghofer on bass) will release its latest CD, Follow the Sun (Concord), in 2010.

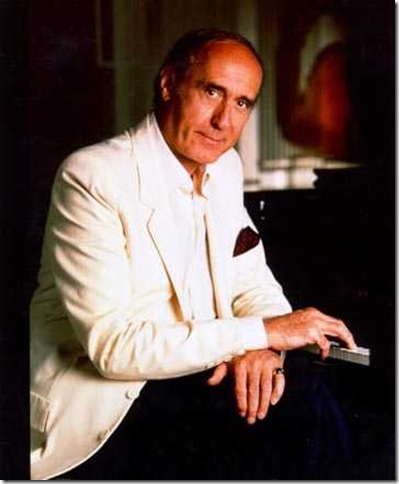

If there was a blueprint for Berg’s multi-faceted career, it may have been created by Dr. Billy Taylor. The 88-year-old pianist likewise played with musical icons before becoming a prolific educator, and the artistic director for jazz at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C.

“Billy is a dear friend, and someone that I’ve admired for decades,” Berg says. “With all of his history, he’s amazing. He just booked my trio for a show at the Kennedy Center in March.”

Founded in 1926, the Frost School of Music also has a storied history among America’s top schools for musical education. Its reputation for preparing students for all aspects of the music industry was an attraction to Berg.

“I’ve had a long-held belief that most schools should be doing things differently,” he says. “Most have performance at the top of the pyramid, and largely separate from the rest of the school. So the scholarships and resources are placed there, and the rest of the programs help to finance that. I feel the different areas should be more integrated, and we were already a school that was broad in its scope.

”We were the first school in the country to have music business as a degree, and the first to have music recording and engineering as a degree. We’ve always had one of the top jazz programs, as well as a strong classical performance program.”

“But the pools of opportunity for musicians are shrinking, and are being replaced by puddles of opportunity,” Berg continues. “At the Frost School, we train musicians more broadly in technology, styles of music and entrepreneurship to allow them to find their niche. So we were a school that had all the pieces in place for the Mancini Institute.”

“Shelly told me that he was essentially going to do at the Frost School of Music what the Henry Mancini Institute did at UCLA,” Mrs. Mancini says. “Only now there’s an additional degree component to it, which makes it even more valuable. So I felt giving him my blessing was entirely appropriate.”

Berg, and the Henry Mancini Institute, may prove to be the additional pieces needed to push one of the leading music schools in the country into elite status. Signs are pointing toward such an ascension.

“There does seem to be a buzz about the school lately,” Berg says. “My plan is to stay here at least 10 years, and my goal is simple — to make sure that it won’t take too many of those years before people think Eastman, Juilliard and Frost, and that they also think that we’re the most exciting of those options.”

Bill Meredith is a freelance writer based in South Florida who has written extensively on jazz and pop music, including for Jazziz and Jazz Times.