There couldn’t be a more refreshing matchup than a symphony orchestra and four brilliant guitarists, which is what I heard Saturday night at the Kravis Center when the Munich Symphony Orchestra of Germany joined forces with the eminent guitar-playing Romero family.

Together with his father Celedonio Romero, and brothers Celin and Angel, Pepe Romero, the soloist Saturday night, helped establish the Romero Quartet — four guitarists — while still a teenager in 1960. (In 1957, their father had emigrated to America from Spain, settling in Los Angeles.)

Instead of a solo violinist or cellist, the Munich Symphony programmed the Romeros in Rodrigo’s solo Concierto de Aranjuez and his Concierto Andaluz for all four players. Philippe Entremont, their intrepid conductor, known locally for his piano master classes at Palm Beach Atlantic University, and of course his stellar career as a concert pianist, conducted with workmanlike precision and unassuming dignity.

The Munich Symphony, founded in 1945 as the Kurt Graunke Orchester, took its current name in 1990. It was short a dozen or more players, especially in the string sections, which at times made for an imbalance of orchestral sound. A pity, because the 53 players assembled did their best to sound bigger, often overwhelmed by the brass.

No doubt these are the cost considerations management must make when touring huge-sized orchestras across vast distances. The difference between American orchestras and their European friends is that we tend to have a core of players, say 20 or so full-time players, and then staff up as the repertoire requires. Our European friends get an annual stipend, underwritten by the state, local government and about 10 percent donations.

Excerpts from Bizet’s Carmen Suites Nos. 1 and 2 opened the evening. Of the seven pieces chosen, the Seguidilla showed the fine musicianship of the lead oboe, Katharina Wichate, and lead trumpet, Aljoscha Zierow, as they played Carmen’s famous song where she tempts Don Jose to be her lover, release her from prison, and help her escape. The Toreador melody was brightly played by the whole orchestra; it thrilled to the core. And Micaela’s lovely tune, here called Nocturne, in which she tries to lure Don Jose back to his village, was beautifully played by the concertmaster, Marian Kraew. I would have wanted more of a singsong sound from his violin, but that’s my taste for this high, delicate soprano aria. The Danse bohème ended the suite: Gentle flutes cleanly picked off the melody as it built to a strong finale, whetting my appetite for the upcoming Palm Beach Opera production of Carmen in January.

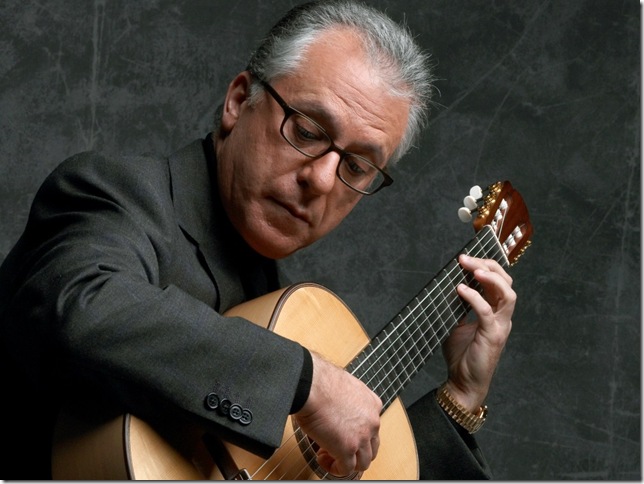

Pepe Romero was next. He played the Concierto de Aranjuez , written in 1939 in Paris by Joaquin Rodrigo, where he had moved at the outbreak of the Spanish civil war. It was Rodrigo’s first great success. Blinded since age 3 by diphtheria, Rodrigo excelled as a composer, forming a special relationship with the Romeros that lasted until his death in Madrid in 1999 at age 98.

The first movement, Allegro con spirito, established Pepe as the master. At the outset, Rodrigo has the solo guitar open the piece instead of the usual full orchestra that would normally begin a concerto. One could have heard a pin drop as the audience sat spellbound as Pepe Romero strummed beautiful chords in a quasi-flamenco style. Building in sonata form the forward insistent rhythms of this movement are reminiscent of the fandango. The recurring introductory chordal motif is exchanged between soloist and orchestra, contrasting with the guitar by the use of solo instruments like the cello, clarinet, oboe and flute.

The second movement, Adagio, has become Rodrigo’s best-known music because of its irrepressible lyricism. A solo horn accompanied by the guitar introduces the theme. Then follows a sparkling solo cadenza that showcased Pepe’s brilliant musicianship. Devotional songs draw the movement to a conclusion using the full orchestra. Lastly the Allegro gentile, with its spirited folk-like Spanish round dances and the elegant light theme that pervades this lively movement, is treated contrapuntally in varying orchestrations before a brief descending figure ends the concerto as the music seems dissolve into nothingness. The Munich Orchestra accompanied Romero with sweet sensitivity as piccolo, flute, oboe, horn and pairs of clarinets, bassoons and trumpets added so much to this combination of power and simplicity achieved by composer Rodrigo.

Move on 28 years to the next guitar item on the program, the Concierto Andaluz. Rodrigo composed it in 1967 for four guitars and orchestra. Imagine returning from intermission to see four places set out in front of the orchestra’s first string section, each with its own leg rest. The Romeros are one of the only classical guitar quartets of real stature in the world today. The two original founding brothers, Pepe and Celin, took their seats. A third generation son, Celino — diminuitive of his father’s name — and a nephew, Lito, took the stage also, to make the four.

Influenced by Paul Dukas, who was his teacher in Paris for five years, and to some extent his friendship with Manuel de Falla, Rodrigo was commissioned to write the concerto by the founder of the Romero Quartet, Celedonio. An exciting bolero opens the first movement. Its rhythm captivates as all four guitarists strum away, with Pepe taking the odd solo to reassuring smiles all around from the players. The Adagio opens with a distinctive eight-tone scale plucked continuously by Celin throughout the movement as Pepe tackles some whirring scales and tricky trills. Then follows the extended cadenza, different from the original, written for the Romeros as a Christmas present by the composer in 1968.

Lito Romero, the young nephew, shone here with some extraordinary playing, his right hand moving across the strings with grace and perfection. Celino, the fourth player, also added a lot to this fantastic cadenza, and the movement ended with Celin still marking out his downward eight-note theme, slowly and deliberately helped out by the double basses in the orchestra.

As the Allegretto began, more smiles of approval from the fabulous four. This last part, a masterfully skilled use of counterpoint, brings out a range of feelings from melancholy to joy in the orchestration. Exciting exchanges go from the soloists to orchestra with some excellent triple-tongue playing by the brass section.

Coming to an end all too suddenly, the Saturday night audience was lukewarm in its appreciation. A few gave the Romeros a standing ovation. Perhaps there’s still work to be done for people to appreciate the consummate skills of making classical music on acoustic guitars.

Massenet’s Le Cid ballet music of 1885 followed, taken from his opera about the knight who liberated Spain from the grip of the Moors. It was anticlimatic. Castanets prevail in the opening movement, “Castillane.” In “Andalouse,” a lovely six-note cello melody anchors this whole movement as it repeats time and again. The “Aragonaise,” a popular and familiar favorite, had conductor Entremont departing from his rigid posture, swaying to the music. The “Aubade” is led by plucked strings and flutes which sounded wonderful throughout the movement. “Catalane” is heavy with strong cello music and throbbing bassoons to a regular beat: vibrant strings trill its ending.

The “Madrilene,” came across as haunting and mysterious. And the exciting “Navarraise” got most people to their feet. It took a while. Can it be we’re spoiled here by larger visiting orchestras in the Regional Arts Series? The Palm Beach Opera pit orchestra is almost twice the size of the Munich Symphony we heard. Put it down to it being the opening concert. There were a lot of empty seats waiting for the snowbirds to arrive in the first three months of next year.

What the Munich band provided was a delightful concert of light classical music, not overly ambitious but just right for this size orchestra. And the four Romeros: What a great night of music-making people missed.