Most of us have faded photos of grandparents or great-grandparents who seem as alien as creatures from another planet or denizens of a sunken civilization. “Fools in old-style hats and coats,” as Philip Larkin terms them in his famous poem This Be the Verse.

Most of us have faded photos of grandparents or great-grandparents who seem as alien as creatures from another planet or denizens of a sunken civilization. “Fools in old-style hats and coats,” as Philip Larkin terms them in his famous poem This Be the Verse.

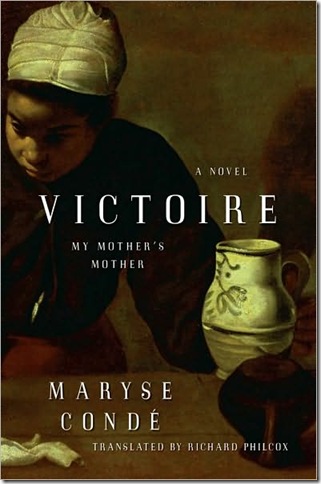

In her latest novel, Guadeloupean writer Maryse Condé sets out to unearth, by dint of research, family legend and imagination, the truth of one such forebear.

In Condé’s case it is a lost and mysterious grandmother, Victoire Elodie Quidal, a poor Caribbean mulatto of no education or distinction, who died before the writer was born in 1933. “All I have of her is a sepia-colored photo,” Condé begins.

“The sight of her never failed to make me feel uneasy. My mother’s mother had that Australian whiteness for the color of her skin. Her soft-colored eyes like Rimbaud’s, set deep in their sockets, were reduced to two Asian slits. She was staring at the lens without the shadow of a smile and without any attempt to appear gracious. Her headtie knotted with two points signified an inferior station.”

The life that Condé half-discovers, half-creates, is one of almost unfathomable harshness. The illegitimate daughter of a 14-year-old girl impregnated by a nameless, faceless white French soldier, Victoire exists at the very bottom of the Guadeloupean social hierarchy. Even black laborers are free to despise her, and her own mulatto relatives put her to menial work, “like a pariah, like a slave.”

Victoire grows up beautiful, silent, illiterate and unquestioning. At 16, seduced by a handsome black radical journalist, she gives birth to Condé’s mother, Jeanne. For a while Victoire, who discovers she has a genius for cooking, works for a family of cousins. But fleeing their abuse, she enters the household of the Walbergs, a prosperous white Creole family where she will spend most of the rest of her life.

Victoire becomes best friends with Anne-Marie Walberg, united by a love of music. Anne-Marie is grateful rather than jealous when her husband, Boniface, takes Victoire into his bed, pleased to be relieved of conjugal duty. Boniface, for his part, grows devoted to Victoire and years later, deprived of her company, pines away and dies. Victoire remains devoted to Jeanne, determined to provide the education that will elevate her daughter beyond misery and hardship.

To my mind Maryse Condé is among the world’s greatest living writers. At first the unusual attack she chooses for Victoire – part documentary, part imagined – seems to deny this book the full breath of invention that makes previous works such as Who Slashed Celanire’s Throat or The Story of the Cannibal Woman so powerful and beguiling.

Neither fully credible as nonfiction nor quite alive as fiction, this book, with its authorial intrusions and invitations to reader speculation, sometimes reveals Condé writing, something that has never happened in her previous stories.

But this is a sly ruse on Condé’s part. It’s important to take note the title designation – “a novel” – and to consider the occasional artlessness of the narrative as intentional, a master novelist making conscious use of the conventions of a lesser genre, the family history. Thus, when the narrator considers whether Victoire and Anne-Marie had a sexual relationship, she declares: “I refuse to believe it.” And then promptly undermines her own assessment by noting “the tradition of both masculine and feminine homosexuality is well established in the Antilles.”

And when Condé writes of Boniface’s relationship with the child, Jeanne, the writer in her squirms in feigned frustration: “How I would like to include here a case of pedophilia! The white Creole swine abusing the little Negro girl, his servant’s daughter. Alas! Boniface Walberg was a modest man of integrity.”

So while Victoire lacks the magical realism lightly present in Cannibal Woman, heavily in Celanire, Condé endows the narrative with a subtler, more difficult magic. Her resolute focus on her grandmother’s story, her touchingly naked attempts to make a personal connection with her, enables Condé to present the reader with a clear, if sidelong, view of Caribbean society, top to bottom, at a time of upheaval and transition.

The seeming artlessness of certain passages, in fact, conceals art of supreme sophistication. It succeeds in revealing Victoire as a fully realized woman of her time and place. It does the same for Jeanne, who grows up intelligent but emotionally rigid and judgmental. Indeed, in this book Condé humanizes everyone who comes under her gaze. The ruling white class is not always wicked, for example, nor is the rising black middle class always noble.

Victoire is another triumph of world literature from a novelist who, well into her 70s, with more than a dozen books available in translation, continues to write with remarkable creative energy and craftsmanship.

Chauncey Mabe is the former books editor of the Sun-Sentinel. He can be reached at cmabe55@yahoo.com. Visit him on Facebook.

Victoire: My Mother’s Mother: A Novel, by Maryse Condé, translated from the French by Richard Philcon, 193 pp., Atria, $19.99.