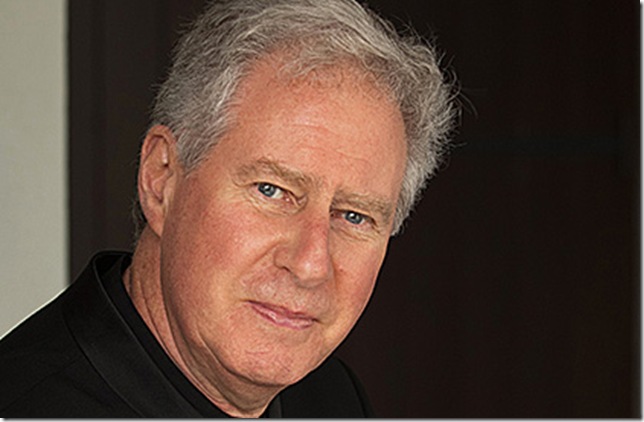

Conductor Stewart Robertson’s final concert with the Atlantic Classical Orchestra at the Eissey Campus Theatre in Palm Beach Gardens on Tuesday afternoon was a memorable occasion. It had a world premiere of an excellent violin concerto, two “Scottish” works to celebrate the land of his birth, and a rousing performance of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony.

Robertson was presented with the original baton Andy McMullan used in the ACO’s first concert 25 years ago by Jerome Rappaport, whose family foundation commissioned the new concerto as well as four other works by young American composers over the past couple years.

The concerto in question, subtitled The Infinite Dance, was by the 33-year-old Chinese-American composer Zhou Tian, who was at the performance with his wife, Detroit Symphony violinist Mingzhao Zhou. Zhou, as he is known to one and all, was born in Hangzhou, China, and came to the United States after high school to study at Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute of Music. He got his master’s degree from Juilliard and his doctorate from the University of Southern California. Besides composing for major orchestras, he now teaches in the music faculty of Colgate University in New York.

The soloist was the young American violinist Caroline Goulding, just 22. The first movement (marked Vivo) begins with Goulding attacking fast, difficult runs in a cadenza-like solo that the orchestra soon picks up on, copying her brief statements. Soon, the soloist breaks out into a lovely melodic piece, quite original in its choice of notes. The rich orchestral background texture, especially from the cellos, helps build to a long sustained high note followed by racing scales from the solo violin. Quick interruptions from the flute in dotted notes make for an original touch.

The brass section takes prominence and the music drifts into what can only be described as a sound from East Asia, perhaps reflecting the influence of the erhu, the Chinese folk fiddle that Zhou said inspired him in this piece. Next comes a cadenza of the most magnificent magnitude musically. Soloist Goulding gave it her very best. Another original touch was the single beat of a huge gong, interspersed twice during the soloist’s cadenza and with one extended gong sound towards the end of her playing. The effect was magical.

The second movement (Andante amoroso) begins with strings playing in a reverent mood in the middle range. The solo violin starts higher, picking up the somber mood and begins a series of elegant phrases, masking the hinted atonality with the romanticism of the music she plays. A lone bassoon picks out some of the soloists notes of this particularly lovely music, so easy on the ear. The full orchestra again join in and the solo violin plays with soaring melodic loveliness.

There’s a pastoral quality that infuses the mood of the orchestral accompaniment. The solo violin goes from low to high in continual scales and then plucks her strings to the accompaniment of the timpani and a solo trumpet, leading to a mysterious ending.

The fast finale, marked Allegro con brio, begins with clever staccato notes penetrating the air. A three-note theme surfaces from the orchestra, then from the soloist. Taken very fast, the trumpets blast out a six-note tune, which the soloist picks up immediately and varies. Syncopated rhythms from the orchestra take over as the soloist answers the orchestra in like manner going back and forth with one another. With slides and glissandos, soloist and orchestra race to a final climax where everything is thrown at it.

The last solo violin music kept resonating in my mind continually for hours after the concert. This is new music I’d love to hear again and again. It is a minor masterpiece.

The concert opened with a fine performance of Mendelssohn’s Hebrides Overture (Op. 26), also known as Fingal’s Cave, written in 1830 after the young composer visited Scotland. (I first heard this as a boy of 10 when Sir Walford Davies, Master of the King’s Musick, described it as perfect “program” music, with sea swells, storms at sea and becalmed seas, all effectively portrayed in Mendelssohn’s clever orchestration.) Robertson got the most out of the orchestra as it played the “winding river” music that dominates the overture.

The next Scots piece was an exquisite miniature by Sir Alexander Mackenzie, called Benedictus (Op. 37, No. 3). Originally written for violin and piano in 1888, he orchestrated it in 1895, when it had its first performance under Sir Henry Wood, founder of London’s famous Promenade Concerts. There is a yearning quality to this music that pervades the whole score, and Robertson, obviously touched by this piece, lowered his baton to conduct with expressive hand commands. The orchestra played this piece beautifully to honor their retiring conductor.

To end its season, the ACO chose the Beethoven Seventh (in A, Op. 92) chose to play Beethoven’s 7th Symphony. Robertson led the first movement with an easy hand, bringing out very refined playing from his musicians.

The famous Allegretto sounded wonderful, and the scherzo found the orchestra nicely knit together; their sound was deft and light in this driving headlong rush of unabated forces. Every section played well; it was a scherzo to remember.

Robertson topped it by taking the last movement extremely fast. Too fast, I thought; this will expose some weaknesses. Not at all. The orchestra musicians rose to the occasion. The speed didn’t allow for the horns to blast out their tune and linger; it was boom, and on to the next: The flutes couldn’t linger, either.

Robertson was in his element, almost dancing on the podium, in complete artistic control. The audience enjoyed every second of this hectic symphonic ride.

It was a grand farewell gesture that will be remembered for many a year from a gent who should have been knighted years ago for his services to music. This time he was the people’s choice as he stood to receive a standing ovation, his glorious band of players joining in the appreciation.

The Atlantic Classical Orchestra and Caroline Goulding perform this program twice today at Stuart’s Lyric Theatre, once at 4 p.m. and again at 8 p.m. Tickets start at $40. Call 772-460-0850 or visit www.atlanticclassicalorchestra.com.