Miami City Ballet presented an outstanding lineup for its Spring Mix program earlier this month as the company wrapped up its much abbreviated season at the Kravis Center for the Performing Arts.

The program was nicely balanced, offering artistic variety with a diverse range of choreographers and composers as well as beautifully showcasing the company dancers.

The program got off to an impressive start April 12 with the visually rich Pictures at an Exhibition by Alexei Ratmansky, the celebrated Russian-Ukrainian-American choreographer. A former dancer with the Bolshoi Ballet, Ratmansky became the company’s director from 2004 to 2008. After leaving Russia, he became the artist in residence at American Ballet Theatre from 2009 to 2023, during which time he created and premiered Pictures at an Exhibition for New York City Ballet (2014). Ratmansky haș set several works on Miami City Ballet as well as numerous prestigious ballet companies around the world and is currently the artist-in-residence at New York City Ballet.

His choreography is known to be expertly crafted, expressive, and exceptionally musical and Pictures at an Exhibition is no exception. In fact, it is a vivid reminder of his enormous talent. Ratmanky’s source of inspiration to create this 35-minute work was the famed piano suite of the same name by Modest Mussorgsky, an innovator of Russian music during the late 19th century. Pianist Ciro Fodere met the challenge of performing the demanding score with an energetic finesse.

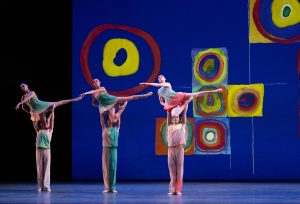

Mussorgsky in turn was inspired to write his unpredictable score after viewing the artwork of his friend, Russian architect and painter Viktor Harmann. Ratmansky skillfully brought this circle where painting, music and dance overlap and influence the other into a beautifully realized work. During the creation of the piece, legendary projection designer Wendall K. Harrington chose to complement Ratmansky’s choreography with huge projections of Color Study Squares with Concentric Circles, perhaps the most recognizable work of Wassily Kandinsky.

Interestingly, this visual work is not a full-fledged painting. It is a just small 9-by-12-inch study that Kandinsky made as a reference for how colors interact when placed next to each other. But when the curtain opened, a huge, bold and bright projection of the 12 concentric, multi-colored circles contained in a grid filled the entire back of the Kravis stage. The projections changed during the different sections of the choreography and dramatically changed the ambience onstage. The sequential images were different sections of the Kandinsky study, which had been enlarged to highlight the rich detail in the original work and served as fascinating changing background for the choreography.

Mary Kate Edwards was captivating in the first solo. There was something delightful about how she threw herself with such abandon into the movement, looking both elegant and lanky at the same time all the while demonstrating a strong underpinning of assured technique. Her gossamer short tunic dress with its enormous blue dot on the front left a trail of her finished movement as she continued to dive and spin against the now dark blue background with red and yellow circles.

Samantha Hope Galler and Chase Swatosh, dressed in pale amber in front of an amber-hued projection, beautifully performed their duet, which was filled with falls and lifts that were suspended or caught mid-air, all of which were sensitively synchronized to the music’s phrasing. The final lift was quite spectacular. Galler was caught in a ball shape by Swatosh and then unfolded to a full stand on his chest as he slowly exited.

The 10 dancers — five women and five men — were dressed in wonderfully diaphanous costumes designed by Adeline André. The movement and music was at first playful but as the work progressed an undertone of solemnity crept in. The quartet for four women had a slight sinister feeling as if they were fairytale witches, as did the duet for Jordan-Elizabeth Long and Francisco Schilereff, which had hints of Hansel and Gretel lost in the woods, whereas the duet for Mayumi Enokibara and Andrei Chagas (which was performed with a lovely clarity and energy between the two dancers) was light-hearted, with a “happily-ever-after” feel to it.

Bathed in a red light that changed the mood, Stanislav Olshanskyi, former principal dancer at the National Opera of Ukraine, gave a strong performance in his passionate solo set to a section of the music that had a very dramatic and a war-like tone to it.

The final section of the score, entitled “The Great Gate of Kyiv,” was inspired by Hartmann’s design for a grand entrance to the city which would symbolize the resilience and strength of its inhabitants. Here the partnering took on a more aggressive look. There was one particular lift that stood out. The woman was held at the man’s chest with one leg tucked and the other aimed straight out like the main gun on a tank rotating to fire on its enemy. Towards the end, all the dancers came onstage to gaze upward. Were they looking at stars or were bombs dropping around them? The final tableau was a projection of a painted yellow-and-blue Ukrainian flag.

The middle of the program had a more intimate feel as we were able to narrow our focus first on Chaconne, an exceptionally powerful solo by the Mexican-born modern dance choreographer José Limón and then on the joyful and ever-popular Tschaikovsky Pas De Deux by George Balanchine.

Choreographed in 1942 to Johann Sebastian Bach’s Partita No. 2 in D minor for unaccompanied violin, Chaconne is Limón’s best-known solo work. The 10-minute tour de force solo (which was originally created for Limón to perform himself) was expertly danced by Satoki Habuchi. Also appearing onstage was violinist Mei Mei Luo.

Though the solo is not always performed with a live accompanist, it was fascinating to be able to watch the dancer and the musician perform side by side. It was just as impressive to see how much Luo’s body responded to the music she masterfully created with her violin and bow, as it was to see how strongly Habuchi connected to the music, letting it enhanced his bold and powerful execution of the movement. The chaconne is both a folk dance form that originated in New Spain — now Mexico — as well as a strict musical form. It is said that Bach added an unexpected emotional layer to his composition in response to the death of his first wife.

For the Tschaikovsky Pas De Deux, Balanchine used a forgotten excerpt from Act III of Swan Lake (rescuing this section of music from the first failed score that Tchaikovsky wrote for the ballet), to create this lively, stand-alone duet in 1960. It is one of his most popular ballets and it has been an audience pleaser for Miami City Ballet since it was added it to the repertory in 1986.

Making their role debuts in Tschaikovsky Pas De Deux, Taylor Naturkas in a pale pink chiffon dress and Brooks Landegger in classic white tunic and tights filled the stage with energy and charisma. Naturkas, who is known for her lightning quick and clean footwork, was a dynamic force as she skimmed across the floor, never stopping for a second. Landegger, tall and blond, was her elegant and competent partner assisting her in pirouettes and lifts.

The ending of this duet is the moment that everyone remembers as it always thrills. On Saturday night, Naturkas fearlessly launched herself and dove through the air not once, not twice, but three times to be caught by Landegger who then lifted high overhead in a final bravura lift to exit.

The evening and the season ended with Jerome Robbins’ Glass Pieces, choreographed in 1983 and premiered by New York City Ballet just two weeks after Balanchine’s death. It was bold statement at the time as it was departure not only with its choice of Philip Glass’ minimalist music, with its repetitive structure, but also for its sleek staging and costumes — all of which were distinctly different for NYCB at that time.

The music for first section was rhythmic and driving and as the huge cast of dancers dressed in a variety of personal rehearsal clothes walked in patterns across the stage, seemingly unaware of each others’ existence, creating a sense of urban detachment while three couples, dressed in sleek solid colored unitards, danced in and out and around the mass of moving people.

The third section was also set to percussion, but with more of a sense of urgency as packs of men moved aggressively across the stage like West Side Story gangs in sleek dancewear tops and tights. The women were added until all 44 cast members were in straight lines formations crossing in battalion fashion.

Nestled in the middle of Glass Pieces was the memorable and sensual duet exquisitely performed by Dawn Atkins and Olshanskyi against the silhouetted backdrop of a long line of women side-stepping in ritualized unison movement that slowly inched across the stage. The pairing of Atkins with her elegantly luscious movement quality and gorgeous balletic lines with the fluid clarity of Olshanskyi’s movement was perfection, and for me, it was the highlight of the evening.