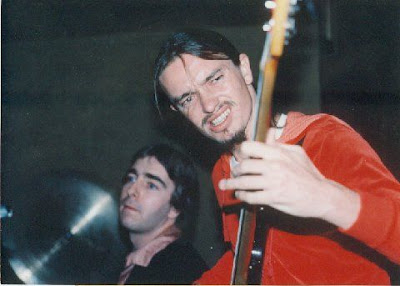

Bassist Jaco Pastorius, performing with drummer Rich Franks

Bassist Jaco Pastorius, performing with drummer Rich Franksat the Players Club in Oakland Park.

(Photo courtesy Ingrid Pastorius)

By Bill Meredith

OAKLAND PARK — A day in the life of the new Jaco Pastorius Park is generally pretty quiet.

The seven-acre park at 4000 N. Dixie Highway in Oakland Park features a football field-sized lawn, benches and a lighted perimeter walkway, but on a recent weekday it sat empty and silent — in sharp contrast to the life of the musical giant it was named for.

It was not so quiet Dec. 1, as Mayor Layne Dallett Walls presided over the ribbon-cutting ceremony to open the park on what would’ve been the late bassist-composer’s 57th birthday. Guests included widow Ingrid Pastorius and her 26-year-old twin sons Julius (who plays drums, his father’s original instrument) and Felix Pastorius, a bassist and rising star.

(Photo by Bill Meredith)

Several South Florida musicians who’d recorded and performed with Pastorius played a free Jazz on the Green concert afterward. On the park’s mobile stage, opposite its 10-foot-high sign at the south end, multi-reed player Ira Sullivan, guitarist Randy Bernsen, percussionist Bobby Thomas Jr. and steel drummer Othello Molineaux recalled Pastorius’ early years in music.

“The opening act was the band from Northeast High School, which Jaco attended,” says Sullivan, whose self-titled 1975 album featured Pastorius. “Afterward, we played jazz standards. Othello called out Alone Together, and Bluesette was the first tune Jaco and I ever played with Randy. In the future, I want to do an evening of the originals I played with Jaco.”

Bernsen, whose first three albums featured Pastorius, said playing in the concert was “like going back in the time machine.”

“Ira, Othello, Bobby, (vocalist) Toni Bishop, (bassists) Jeff Carswell and Nick Orta, (keyboardist) Mike Orta, (drummer) Danny Burger and I played A Night in Tunisia and Donna Lee. Ira was telling Jaco stories, and everybody was smiling. We must have all been feeling the same deja vu.”

The event was nearly 22 years in coming. Pastorius, who battled manic depression, died at age 35 on Sept. 21, 1987, from injuries suffered in a brutal beating. Nine days earlier, he’d encountered Luc Havan, a bouncer and martial arts expert who’d violently denied him entry to an after-hours club in Wilton Manors, a suburb of Fort Lauderdale.

Havan later pleaded guilty to manslaughter charges and was sentenced to 21 months in prison and five years’ probation. He served four months before being released in 1989, according to press reports.

But a South Florida fan group, headed by Robert Rutherford, wanted Pastorius remembered for his many triumphs, not his untimely coda. Rutherford started a two-and-a-half-year grassroots movement to name the park for Pastorius, and wouldn’t be denied.

“There was pretty severe opposition at first from the other side of Jaco’s family,” Rutherford says of Pastorius’ ex-wife, Tracy, and their children, John and Mary Pastorius.

“But in the end, John was there for the ceremony,” says Ingrid, “which was important.” John, in fact, sang Happy Birthday to his father with Felix and Julius before the ribbon-cutting.

John Francis “Jaco” Pastorius was born in Norristown, Pa., but grew up in Oakland Park. He met Tracy in high school in 1967, and Ingrid nearly a decade later in South Florida, where she still resides in the Deerfield Beach home Pastorius bought in 1979.

At age 19, Pastorius pulled the frets out of his 1962 Fender Jazz Bass and filled in the slots with wood putty to create a fretless instrument. Within six years, he would tour and record with R&B stars Blood, Sweat & Tears and jazz piano icon Paul Bley; stand out on landmark releases by guitarist Pat Metheny, singer/songwriter Joni Mitchell and fusion supergroup Weather Report; and release his self-titled 1976 debut.

Its first track was Charlie Parker’s Donna Lee, on which Pastorius did the unthinkable — effortlessly playing the saxophone lines of a bebop classic on bass.

The jazz world, which had previously embraced such warp-speed technique in horn players like Parker, pianists like Art Tatum and drummers like Buddy Rich, had a new hero. The supportive, fretless acoustic bass had been the rule in jazz, even if no upright player was capable of playing such figures. Pastorius shattered the rules with his otherworldly abilities and fretless instrument, forever transforming bass playing, and composed future jazz standards such as Three Views of a Secret, Continuum and Barbary Coast.

“The naming of the park was long overdue,” says Rutherford, who’s also organized a petition for a commemorative Jaco Pastorius postage stamp. “I’m surprised no one thought of it years earlier. There was nothing in Oakland Park with his name on it, not even a park bench.”

Future Jaco Pastorius Park plans include more concerts, a community center and possible expansion.

“The first Jimi Hendrix Park was established about two years ago,” Ingrid says, “so in the scheme of things, it took Jaco a shorter time.”

Bill Meredith is a South Florida freelance writer who has written extensively about jazz for Jazziz and Jazz Times.

(From YouTube, here is Pastorius playing Portrait of Tracy, from the Montreux Jazz Festival in 1976: