Editor’s note: Here are late reviews from recent concerts:

Cleveland Orchestra (Jan. 25, Kravis Center)

Slowly and surely since his death in 1975, the music of Dmitri Shostakovich has established itself as a vital and permanent part of the canon, with music from almost every genre in his output – with perhaps the exception of operetta and film scores – getting regular hearings and recordings.

At the time of the “old” New Grove Dictionary, in 1980, the prediction as expressed there was that Shostakovich’s symphonies would be the standard-bearers of his work. But that has not quite turned out to be the case. While the First, Fifth, Ninth and Tenth symphonies are regularly heard, the rest of them are harder to find on concert programs, and it’s been in concerti and chamber music most of all that Shostakovich has become a familiar concert face.

String quartets play all 15 of his quartets, as well as doing complete cycles, and works such as the piano trios and the quintet, the cellos and viola sonatas, plus his great cycle of preludes and fugues for solo piano, pop up everywhere. The first of his two violin, cello and piano concertos are standard fare these days, too, with perhaps the Second Piano Concerto, written for his son Maxim, coming into its own.

The Seventh, Eighth and Fifteenth symphonies should be programmed much more often, but the others present problems of one kind or another that make them harder to do. With the Sixth Symphony, though, no such problems (i.e., choruses, vocal soloists, instrumentation) exist, which leaves the work’s fate up to advocacy.

In Franz Welser-Möst, the artistic director of the Cleveland Orchestra, the Sixth has found a champion, and in the orchestra’s beautiful, muscular reading of this work Jan. 25 at the Kravis Center, audiences learned why they should know this piece much better.

The Sixth is tough to grasp because it starts with a long slow movement and is followed by two fast ones, which goes against the grain of the usual fast-slow-fast symphonic arc. Leaving aside the question of why that arc should still be with us, the music itself actually comes off as a return to vigor after a time of sadness, or perhaps a slow rising from the floor of a boxing ring.

Welser-Möst led his charges, in town for a runout on their annual Miami residency, through a most persuasive account of the work, beginning with an opening theme in the lower strings that was straightforward and sober, not overwrought, which is good wood for building. There was distinguished playing from each of the instrumental soloists that play such an important part of the sonic landscape at the end, and careful attention paid to the trill-and-suffix that runs throughout, with different shades of meaning brought to it each time.

The second movement Scherzo had a welcome lightness that contrasted well with the drawn-out agony of the first. Welser-Möst wisely avoided the temptation to stress the sardonic aspects of the music and kept it lilting, so that the final scales in the upper winds evaporated rather than parked on an upper level.

And the finale is a barn-burner, one orchestras should look forward to doing. Again there was a basic lightness of approach, and quite a fast pace, that made the music more exciting, more fun. Concertmaster William Preucil’s midway solo was right in keeping with the spirit of the proceedings, and the climactic closing bars, full of brass and percussion, came as a joyful explosion after the orchestra had worked up a tremendous head of steam.

The Shostakovich ended the concert, which began with a performance by the Russian-born pianist Yefim Bronfman of the Brahms Piano Concerto No. 2 (in B-flat, Op. 83), and was followed by a new work, American composer Sean Shepherd’s Wanderlust, a three-part tone poem.

The Shepherd work, which evokes the young composer’s Nevada home, the British town of Aldeburgh (and its most famous resident, Benjamin Britten), and the Gehry museum at Bilbao, Spain, is distinctive primarily for its explicit colors. Shepherd is a composer with a good feeling for them, and in the first movement (Prevailing Winds), there is a good deal of high flute and piccolo sound-wash contrasted with brass groupings, all of it creating a mood of dust and wind.

The second movement, Seagulls on High, is even more atmospheric, with a soft wind chord heard early that anchors the outbursts of instrumental extravagance throughout. The third, Bilbao, has a repeated three-note motif running through it that was played by the violas with a deliberately mechanical, impassive regularity.

This music’s interest lies primarily in the skill with which the various color bursts are scored. For all the volume that he calls for in parts of the piece, overall it is gentle and delicate, and he tends to score with a Debussy/Ravel-style sense of instrumentation, one with plenty of air beneath it and in its spaces. Brasses, for example, tend to be used as big, soft supports for the strings and the winds, not as mighty deliverers of chorales or bombast.

The concert opened with the Brahms concerto and Bronfman, one of its frequent practitioners. Bronfman has specialized in big-fisted repertoire such as this work and the Rachmaninov Third, and he was able to supply much in the way of massive sound at the concert.

The performance as a whole had something of a lumbering quality about it. The second movement was taken at a pokey tempo, and when the strings entered with their downward line, they did so demurely, rather than with strength and drama, and it took Bronfman to show them the aggressive way to play it at the end of the movement, when the roles were reversed.

The horn solo in the first movement and the cello solo in the third were entirely beautiful, and soloist and orchestra meshed lovingly, with Bronfman perhaps coming in a little bit ahead at the ends of the movements, particularly at the end. But while his playing was not entirely spotless, it had grandeur and weight, which is perfectly suitable for this music. – Greg Stepanich

Euclid Quartet (Jan. 24, Flagler Museum)

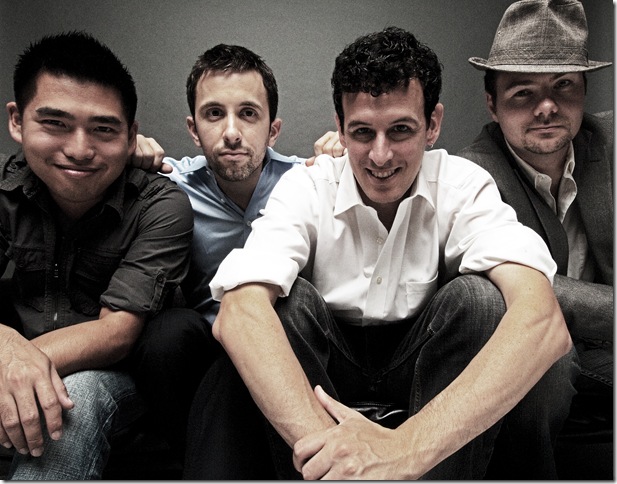

The four young men from four corners of the world who make up the Euclid Quartet proved Jan. 24 that music is indeed the language that breaks down barriers and cultural differences.

The Euclids played their hearts out for the full house attending their concert at the Flagler Museum, a go-to venue for quality musicianship of this kind in Palm Beach. The setting alone, a fine neo-baronial hall built by the great railway mogul Henry Flagler, is worth the experience. Upon entering, one gets a sense of the Gilded Age in America. And your ticket includes champagne and hors d’oeuvres served after the concert while you have a chance to meet the artists, which continues the exceptionally high quality.

Why Euclid? Because, explained John Blades, executive director of the Flagler, Euclid Avenue in Cleveland is where quartet was formed. It is a center for culture and, coincidentally, the place John D. Rockefeller and his company secretary, Henry Flagler, made their fortunes in oil. Flagler used his money to build railroads to Florida. A billion Flagler dollars, dispersed among various trusts in America, yields $50 million for the arts and similar activities annually, Blades said.

Winners of the prestigious Osaka International Chamber Music Competition, the Euclids are based at Indiana University-South Bend. They opened their program with Haydn’s Quartet No. 54 (in B-flat, Op. 71, No. 1), written in 1793.

It begins with thickly textured chords, played vigorously by the Euclid. They have a beautiful tone which was made to sound even more lovely by the live acoustic of this hall, most suitable for chamber groups. Their fresh attack and quality put me in mind of the Emerson, whom I heard in December. The cello seemed too dominant at first, but cellist Si-Yan Darren Li, sensitive to the others, adjusted his level of playing and blended in perfectly.

The second-movement Adagio has an underlying cello accompaniment at its center that Li played beautifully. In the minuet, the music danced along; violist Luis Vargas, dancing on his seat, looked as though he was about to burst into song. A fine balance of all four instruments was achieved here. The final movement, Vivace, was taken very fast. It displays exuberant syncopations and a drone-like bass. The quiet, surprise ending had nobody fooled in this audience, who recognized first-class musicianship with warm applause.

Puccini’s short composition, Cristantemi (Chrysanthemums), followed. It was written when Puccini learned of the death of Amadeo I, the former king of Spain, in 1890. He seldom wrote pieces for string quartets, but was obviously moved to do so here, writing it in one night. It echoes the French impressionist style of Debussy. The Euclid played it exquisitely.

Grieg’s First String Quartet (in G minor, Op. 27) ended the program. Based on a poem of Ibsen’s, The Minstrel, it’s the tale of disappointment in love, which may have had some significance to the composer, who was obsessed by this theme during composition.

The first movement is quasi-orchestral in it scoring, with hints of the composer’s Piano Concerto, Wedding at Troldhaugen and Peer Gynt. The second movement is almost song-like, with some excellent high notes played on the first violin by Jameson Cooper. There’s a longing Grieg manages to convey here that digs into the human psyche. The third movement, a brief Intermezzo, has enormous charm. The first and second violins play a melody over plucked strings on the cello and viola. Second violinist Jacob Murphy is the consummate teammate for Cooper, reliable and steady in all his playing.

The melody finds nowhere to go and ends up in the rhythm of a halling, the Norwegian folk dance played in turn by each instrument. It’s catchy and fun, and familiar. For some reason best known to Grieg, the last movement shifts from the fjords and waterfalls to Italy for his finale, a tarantella. But the longing returns in the last few bars and we are back in Grieg’s homeland.

This foursome reminded me not just of the Emerson but the Tokyo String Quartet, and it might be that they deserve to rank in that august company. The Grieg quartet, in any case, received a brilliant reading, and was met by a well-deserved standing ovation.

We were, after all, in the presence of great artistry. – Rex Hearn

Palm Beach Opera 50th Anniversary Gala (Jan. 20, Kravis Center)

Anniversary celebrations of opera companies can be awkward and inward-looking. What is there to do but sing? I’ve attended many such occasions. Some were boring, some too long. And quite a few, full of self-centered pats on the back.

It was not so at Palm Beach Opera’s Golden Jubilee on Jan. 20 (the concert was repeated Jan. 22). Packed houses in the Kravis Center were treated to five opera scenes in two hours, and short, sharp, precise comments on the history of the company. Written by its general director and co-host, the suave Daniel Biaggi, his was a polished performance, exuding all the confidence needed to face the next 50 years.

A lot of planning and rehearsing went into this important event, and it ran smoothly. The opera stars were stellar, and in top vocal form, as was Bruno Aprea, the artistic director and conductor. This celebration, including the sets, was underwritten by Helen Persson’s gift of $1 million. Angels like Persson are few. Her generosity is a living example to today’s rich young computer barons.

The Googles, Facebooks, Amazons, Apples and such must repeat what the Carnegie, Vanderbilt, Ford and Rockefeller fortunes did for the arts in America’s 19th and 20th centuries. Which young wizards will step up to take the lead, show they know their civic duty, and be remembered as the greatest artistic philanthropist of the 21st century?

The retired baritone Sherill Milnes, the other co-host, spoke of his 40 years in opera and

had a funny story about singing his first Germont as a young man. He had to arrive early to disguise himself as an older man with makeup. As he grew older, all he eventually needed was 10 minutes because his natural looks took over.

Selections from Verdi’s La Traviata opened the event. Soprano Sarah Joy Miller sang a delightful Sempre libera, with all the tough high notes and trills intact. Her voice could use some more focus, but she gave the evening a thrilling start.

Johann Strauss II’s Die Fledermaus followed: Lauren McNeese, mezzo, was a convincing Prince Orlofsky, a pants role. And the wonderful soprano Ruth Ann Swenson gave us a glorious Czardas.

Brazilian tenor Atalla Ayan and Swenson as Rodolfo and Mimi, respectively, gave a lovely performance of the famous love duet from Act I of Puccini’s La Bohème. Ayan’s tenor was perfect for Che gelida manina, and their two voices blended beautifully as they walked offstage.

The highest points came for me in the extracts from Bizet’s Carmen. Denyce Graves-Montgomery was smashing in the Habanera. Her full-throated mezzo sound is beautiful, rich and unique.

Even better was the clash between Graves-Montgomery and tenor Brandon Jovanovich in the Act IV excerpt that came next. Carmen refuses Don Jose’s love, and he stabs her to death. Jovanovich was convincing and brilliant in his vocal delivery of this stressful, wide-ranging piece. These two fine artists were met with rapturous applause, again and again.

What better work than the Grand Finale from Act II of Verdi’s Aida to end the program? Soprano Angela Brown was magnificent as Aida, and the choristers of the Palm Beach Opera were superb in this and their support of all the other scenes. Bravo to them, and to chorus master Greg Ritchey.

Stage director Dona Vaughn made the whole event run slickly, in the best sense of that word. This was an anniversary concert that will stay in the memory for a long time to come. And after all that, the best thing to say is: Here’s to the next 50 years. – R. Hearn