The authentic-performance movement of three or so decades ago had several benefits other than just the experience of hearing familiar Baroque and Classical music in fresh guise.

What it also did was open the doors to rediscovery of celebrated composers from the past whose work had been overlooked in modern times, and on Jan. 18 at All Saints Episcopal in Fort Lauderdale, Seraphic Fire did just that with composers of the French High Baroque.

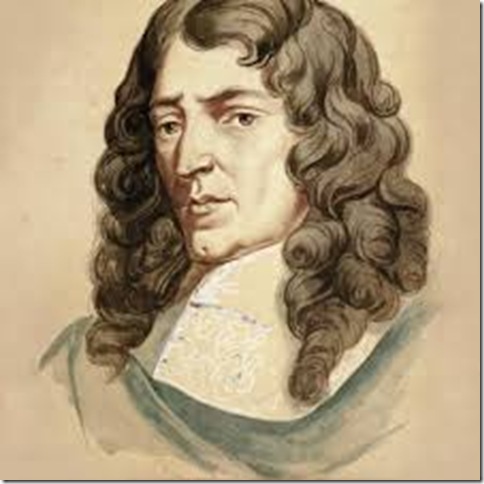

While the names of Lully and Rameau are reasonably well-known to casual concertgoers, and works by these composers were sung by the choir in its usual expert fashion, it was the music of Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1643-1704) that made the strongest impression in this concert of sacred music devoted to composers associated with the Chapelle Royale of King Louis XIV.

Conductor Patrick Dupré Quigley has a great admiration for music from this period, and sacred music in particular. Previous Seraphic Fire concerts have included an evening of motets by François Couperin and Louis-Nicolas Cléramabault, and these two composers also were represented on the Jan. 18 program. The 13 singers of the Miami-based choir were accompanied by a very fine continuo group of organist Olukola Owolabi, gambist Patti Garvey, and violone player Philip Spray.

Quigley, directing as ever with a strong, energetic beat, led his singers in performances that matched the spirit of the composer most admirably. The first piece on the program, a Salve Regina (H. 24) by Charpentier, features the kind of word painting that was popular in 16th and 17th-century madrigals, with voices climbing chromatically as the text talks about sinners sending their pleas to heaven, and then slithering down, Gesualdo-like, on the words In hac lacrimum valle (in this valley of tears). The singers handled it with laudable precision.

Throughout the concert, Charpentier’s remarkable responsiveness to text was evident, giving his music a light, flexible quality that was beautifully explored by the singers. Several of the dozen pieces on the program ended with a cadential formula in which the final chord gradually resolves from a suspended fourth down to a third; at times, the choir sounded tentative about hitting that suspension dead-on and letting it slowly unfold.

Given the various forces needed for each piece, singers rotated in and out of duos and trios as well as joining the full ensemble, and voices of differing colors added variety to music that had a general similarity of emotional temperature. Particularly notable work came from the soprano Jolle Greenleaf, whose confident, big sound carried forcefully through long, difficult passages, and the tenor Steven Bradshaw, who sang in a haunting haut-contre style whose poignant tone color added a touch of medieval flavor that does so much to tie the music to the chansons of earlier centuries.

As with most Seraphic Fire concerts, there were several moments in which the choir and Quigley entered the Polyphony Zone, and the music simply unspooled with a kind of radiance and inevitability that suspended anything but sheer sensual enjoyment, and a knowledge amid all that of the extraordinary corpus of great music that would enter the consciousness only of specialists and scholars were it not for the efforts of groups like this. In works such as Rameau’s Laboravi clamans and Charpentier’s Laudate Dominum, Seraphic Fire brought the sound of the sacred past alive in a way that helped explain why music of such firm belief, written for a specific purpose, survived with its glories intact to greet a much more skeptical age.

Seraphic Fire takes on a seminal J.S. Bach masterwork, the Magnificat, in its next series of concerts, which will be accompanied by the Firebird Chamber Orchestra. Concerts are set for Friday, Feb. 14, at All Saints Episcopal in Fort Lauderdale, at 8 p.m. Saturday at First United Methodist Church in Coral Gables, and at 3:30 p.m. Sunday at St. Gregory’s Episcopal Church in Boca Raton. Call 305-285-9060 or visit www.seraphicfire.org.

***

Soloists impressive, but work remains for Lynn Philharmonia

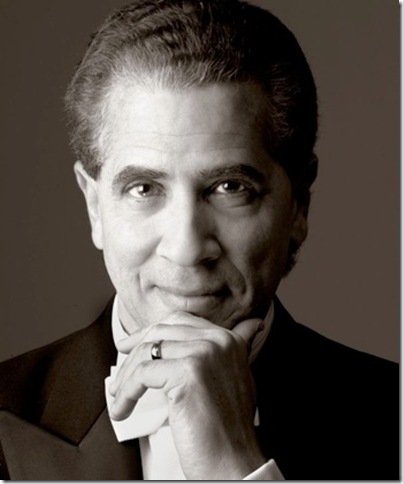

The student orchestra at Lynn University’s Conservatory of Music, which has been gradually enlarged to full-size symphonic status over the past few years, entered a new phase this season with the accession of Guillermo Figueroa to the director’s chair.

The expectation is that Figueroa will be able to take his student charges to the proverbial next level, and he starts from a position of strength: Area audiences in need of symphonic sound greater than the chamber-size groups hereabouts reliably turn out in substantial numbers to hear this large group of talented students training to be music professionals.

Figueroa took over for the third concerts of the season in November, which featured the winners of the conservatory’s concerto competition, but on Jan. 18 and 19, he was at the helm for the first time of a standard Lynn Philharmonic concert, joined by soloists David and Carol Cole, longtime Lynn professors of cello and violin respectively, and husband and wife.

The Coles were soloists in the Double Concerto (in A minor, Op. 102) of Brahms, a wonderful work that always leads me to wonder why more composers didn’t write concertante works like this. Both played well, with thorough professionalism and a good sense of command and ensemble. David Cole’s solo entrance in the first bars of the first movement was passionate and eloquent, and Carol Cole’s entrance a few bars later equally so.

In the second movement, the Coles’ beautiful statement of the main theme quickly erased the memory of the painfully out-of-tune opening notes from the orchestra, and they gave the triplets of the secondary theme a welcome gentleness. Figueroa chose a good, snappy tempo for the third movement, and both soloists got on board with a vigorous, driving approach while staying within bounds of the lightness the primary theme needs. The sold-out hall Jan. 19 at the Wold Center for the Performing Arts gave the Coles a strong ovation that was well-deserved.

After the half (the first half opened with a decent performance of Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro overture), Figueroa took the orchestra through a contemporary piece by a fellow Puerto Rican, Roberto Sierra. He is a popular living composer, and the Fandangos, which the Philharmonia played next, is probably his most celebrated piece, as Figueroa said in brief remarks to the audience. Based on a fandango by the Spanish Classical composer Antonio Soler (1729-1783), Sierra mixes parts of its tunes and its back-and-forth tonic-dominant motion with fragments of other things to make for a colorful, exciting piece that pays homage to the folk heritage of this music while pointing things in a new direction.

This sounded like the piece that had received the most rehearsal on the program; it had the steady thrum of Ravel’s Boléro (another inspiration for Sierra) underneath bubbling orchestral writing that pushed inexorably toward a powerful conclusion. For the most part, the orchestra played with crispness and energy, and the audience responded warmly.

The final selection was the suite Richard Strauss assembled from his most-beloved opera, Der Rosenkavalier, performed as the classical music world celebrates the 150th birthday this year of the German composer. The Lynn Phil is a large orchestra, and when it was going all out in the waltz tune that dominates the suite, it made a seductive impact, and there was much sensitive playing in the nostalgic music from the last moments of Act III just before the closing section.

On balance, it was a good performance, and one the audience found irresistible.

But here’s my caveat: This is an orchestra that has for years given strong performances of difficult works, and done so regularly despite the fact that its chairs regularly turn over as the members graduate. The biggest trouble this year has been a weak brass section that has some fine individual players but an ensemble that cannot be relied on to hit their marks when it counts.

The first two concerts of the year, under Dean Jon Robertson, demonstrated the same difficulty on display Jan. 19. The worst offender in this regard was the Dvořák Ninth Symphony at the end of October, which was full of out-of-tune playing in winds and brass, so that the listener winced in anticipation of the next important entrance: Would they make it?

I bring this up now because this is an orchestra that is about to do more Strauss next month —Don Juan, an orchestral tour de force — and in March is doing the Mahler Second Symphony with the Master Chorale of South Florida. In order to do those works successfully, the orchestra’s sections need to be better drilled. String intonation and ensemble need to be as precise as possible; it’s too inconsistent now. The same goes for the winds, and the brasses are going to need extra rehearsal to get things in shape, judging by the three concerts I’ve heard this year.

Yes, this is a student orchestra, and audiences are willing to give it some leeway. But it gets large audiences, it charges real money for its concerts, and it’s playing the most difficult masterworks of the repertoire. In order to justify all that, and fulfill its promise — again, this is one of the few full-size local orchestras we have — some serious attention to basics is going to have to occur before the next two concerts.

Figueroa deserves some time to get things in order at his new job, and it will be a couple years before his impact can be fairly judged. Here’s hoping he’s able to clean things up for the rest of the season, at least enough to have general reliability across the spectrum of his band.

The Lynn Philharmonia’s next performances are set for Feb. 8 and 9 at the Wold Performing Arts Center on the Lynn campus in Boca Raton. The program features Richard Strauss’ Don Juan, the William Tell overture of Rossini, and the Fourth Symphony (in F minor, Op. 36) of Tchaikovsky. Tickets: $35-$50; call 237-9000 or visit events.lynn.edu.