Lynn New Music Festival: Donald Waxman (Oct. 4, Lynn University, Boca Raton)

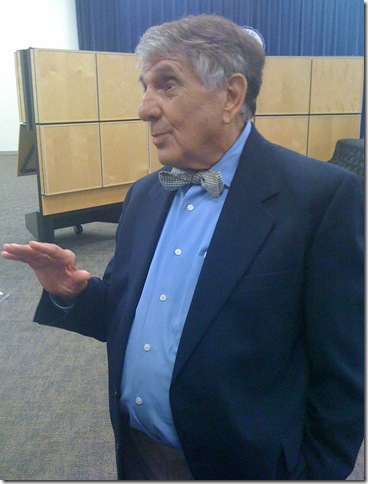

The composer Donald Waxman turns 87 later this month, but his compositional muse shows no sign of slowing down.

The special guest last week for the New Music Festival at Lynn University, founded by pianist Lisa Leonard and now in its seventh year, Waxman has had a long, distinguished career in composition and publishing, and has been a resident of Boca Raton for more than 20 years. The all-Waxman concert that closed the festival featured four chamber pieces and the world premiere of an orchestral overture. The five pieces covered a period from the mid-1960s to the present, and showcased a thoroughly professional composer with a knack for immediately attractive material that he develops in sometimes unusual ways.

Waxman’s new Announcement for Orchestra, played by the Lynn Philharmonia under Jon Robertson, the conservatory’s dean, proved to be a forthright, largely sunny piece with two basic sections: a fanfare-like idea for the brasses, and a bubbly, nervous idea for the rest of the orchestra, punctuated by surprise accents in the piano. It had sort of a futuristic dance-band feel that stood in sharp contrast to the solemnity of the brasses, and it made for a very entertaining opening piece.

The orchestra, playing in the Green Center on campus (normal arrangements being disrupted for the upcoming third presidential debate), sounded somewhat ragged at the edges, but strong overall. The quality of the brass playing augurs good things for the brass section in general, in the past the weakest part of the Philharmonia. Thursday night, they came up with a good blended sound, with few noticeable fumbles.

The Serenade and Fantasia, written in 2003 for violin and piano, came next. The violinist was Olesya Rusina, the pianist was Olga Kim. The first theme of this piece, which Rusina played with sensitivity and warmth, was a good example of the kind of theme Waxman was able to devise for all the pieces on the program: Tuneful, memorable, emotionally direct. The theme was easy to follow, too, as it left its relative serenity for darker climes, and then transitioned to an aggressive, virtuosic cadenza.

Rusina played the lyrical passages very nicely, but during the busier passagework and the extravagant cadenza, she sounded less confident; the notes were there, but needed some more presence. Doubtless with a longer time to prepare, all of the parts of the piece would have been equally persuasive. As it was, she and Kim gave the work a good account.

A Suite for Flute, Oboe and Cello, written in 1986 for the Huntingdon Trio (and in fact, its last commission), followed, with flutist Doug DeVries, oboist Asako Furuoya and cellist Natalie Ardasevova. This is a very fine piece of chamber music, written with great skill for the three instruments and cannily making the most of their separate sound qualities.

In five movements, the suite covered a variety of moods from the bustling, charming theme with which the work opens, the solitary chill of the fourth movement, called Night Song, and the bigness and exuberance of the closing Toccata and Chorale. The three student musicians handled its difficulties ably, and Furuoya in particular was impressive throughout; she’s an oboist with a really big sound and excellent technique who managed to fill up the space of a room not meant for musical performances.

After the intermission, pianist Agnieszka Sornek performed the earliest work on the program, the Fantasy Nocturne, which Waxman composed in 1965. Here again, the piece begins in simplicity, with a classic nocturne rhythm outlining a major triad and then the chord a minor third above it, over which a sweet, melancholy melody then unfolds. Sornek played this with delicacy and beauty, setting the stage for an elaboration of the mood and theme into a kind of lush overgrowth, with colorful patterns breaking out and an atmosphere reminiscent at times of Scriabin.

Overall, quite a good piece, and one that would be a fresh addition to an inventive pianist’s program.

The concert closed with the Divertimento for Flute, Clarinet, Violin, Cello and Piano, composed in 1976, and the work with a clear indebtedness to the French styles of the 1920s, Stravinsky and Milhaud especially. That was especially true of the first movement, a sassy, impish overture well-played by the quintet of flutist Kelly Barnett, clarinetist John Hong (another standout Lynn woodwind player), violinist Aziza Musaeva, cellist Jenna McCreery and pianist Carina Inoue.

Musaeva and McCreery were in the spotlight for the Serenade movement, which was dominated by a very engaging tune, and in the fourth movement, titled Arias, Musaeva played her elaborate solo with serious force. The last movement, titled Burlesk Finale, demonstrated the spirit of dance in so much of this music, and in this case, the spirit of ragtime (which in the mid-1970s was all the retrospective rage). It’s expertly written for its combination of instruments, and it was a delightful way to end the piece and the concert.

The composer revealed in these pieces is a writer with a natural melodic facility, a fine ear for instrumental color, and a clear willingness to absorb popular dance forms into his music. That may be a legacy as much of his service in World War II as his affinity for Les Six, but it gives his writing a communicative lift that makes it never less than entertaining, even when he enters a knotty harmonic and rhythmic realm.

At times, one wished that he had done more with some of the themes (the Night Song from the suite, the Serenade from the divertimento, the Fantasy Nocturne), let them extend a little longer, before going off in a different direction. Coming up with that basic material is the primary responsibility of composition, and Waxman had some fine building blocks with which to work.

Lynn’s new music festivals have brought some valuable attention to bear on contemporary music (full disclosure: I was invited to take part in a panel discussion about contemporary music moderated by Waxman earlier in the festival), and they serve a good pedagogical purpose by giving students completely unfamiliar music to learn and present in a hurry. Donald Waxman, who may be best-known for his teaching pieces for young pianists, is an estimable composer whose work, like that of so many other American composers, should be heard far more frequently on concert programs in his native land.

The audience at the Green Center certainly appeared to enjoy each of these works, and the concert was an object lesson in how much creative effort has been expended by fine classical composers in the United States, but whose work nevertheless retains a frustratingly low profile.

***

Trillium Piano Trio (Sept. 23, St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Delray Beach)

As it has done now for several seasons, the Trillium Piano Trio of Jupiter opened the new season of concerts at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, and this year brought along a good piece of fresh repertoire to deepen its offerings.

The Piano Trio of the Swiss composer Frank Martin, written in 1925, is based, as its subtitle says, on Irish folksongs, and Martin made a serious, sinewy piece out of the tunes. The trio – pianist Yoko Sata Kothari, violinist Ruby Berland and cellist Benjamin Salsbury – gave a decent account of the piece, helping to acquaint the rather large concert audience with a worthy work of early 20th-century modernism.

Standing out in this performance were Salsbury’s solo work at the beginning of the second movement, which showed off his dark, warm sound, and the overall high spirits and rhythmic infectiousness of the third movement, a vigorous jig. But while it was an effective, engaging reading overall, it lacked a certain lived-in quality that would have allowed some more contrast and drama. The church itself doesn’t offer a lot of reverb, which would help, but the work is written in definable sections, and they needed to be set off with greater light and shade.

The concert opened with the lone, and late, Piano Trio (Op. 120) from 1923 of Gabriel Fauré, which like all this master’s late works has an elusive, refined character that can be hard to bring off despite the beauty of Fauré’s first-rate melodic gift, much in evidence here. Kothari opened the work with gentleness and mystery, and solo passages from Berland and Salsbury were deeply Romantic and evocative.

The end of the second movement, which begins with simple chords like one of Fauré’s songs, climaxes in an intense dialogue between violin and cello that needs a tight focus by both players to make narrative sense. It was somewhat aimless in this performance, though interesting; a stronger sense of dramatic line would have helped. The finale is difficult to bring off, composed as it is of a dramatic string motif that reminds everyone of Pagliacci (a coincidence, Fauré said), and a jumpy, skittish piano motif that contrasts starkly with it. Kothari did a good job of bringing it out, and the movement came off effectively.

The concert closed with the second of Mendelssohn’s piano trios (in C minor, Op. 66). It’s a beautiful, underrated work, even with its secure repertory status. The tense opening theme is stated in unison by violin and cello after the piano entrance, but Berland and Salsbury were not in tune with each other, which spoiled the effect. The rest of the movement had strength and drive, which helped make up for it, and Kothari had clearly worked hard to bring off her cascading solo figures in the middle.

The second movement had a swift kind of lightness despite its Andante espressivo marking, which is more in keeping with older practice and fits the music better. All three players brought plenty of prettiness to this music’s long melodic outpouring without overdoing it, which was refreshing. The exciting scherzo was taken a nice brisk clip that didn’t flag, much to the musicians’ credit, and the finale was offered in good storm-and-calm style, with plenty of passion for the outer sections and graceful sturdiness for the chorale (which is Mendelssohn’s own, though drawn from Gelobet sei Du, Jesu Christ).

All three of the musicians in the Trillium Piano Trio have considerable ability and experience, and they are to be commended for continuing to pursue this substantial literature. They play with skill and dedication, but they could use some more ensemble time together so they could add more contrast, more shape, and a more organic feel to the ebb and flow of the music. Some more frequent performances, in other words, are in order. And if that happens, the payoff could be handsome.