Boca Raton Symphonia (Sunday, Jan. 23, St. Andrew’s School, Boca Raton)

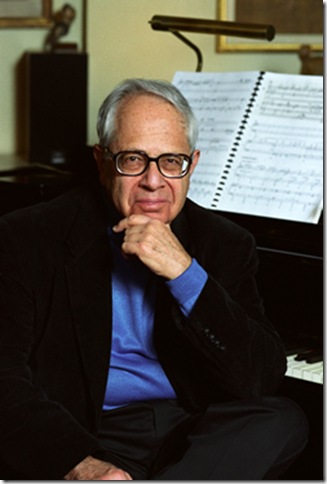

The eminent American composer and educator Gunther Schuller was joined by a very young cellist Sunday afternoon in a concert by the Boca Raton Symphonia that was one of the most polished this group has offered in some time.

From the tightness of the Cosi fan Tutte overture that opened the concert at St. Andrew’s School’s Roberts Theater to the sparkle of a comic suite by Jacques Ibert that closed it, the Boca Raton-based chamber orchestra seemed to be doing its utmost to play well for Schuller, who was guesting for music director Philippe Entremont.

And there was plenty of evidence of it, beginning with the Mozart overture, which had little to none of the usual test-tuning you often hear in the usual slow Classical introduction, but was clean and sharp right off the bat. Schuller conducts with a loose beat, shaping the music rather than beating time, and he gets good results. This was limpid, clear, vital Mozart, and it was played with gratifyingly solid intonation and accuracy.

The young South Korean-born cellist SuJin Lee, currently a Columbia University undergraduate, has been concertizing in public since age 7, and for reasons that become plain once you hear her play. She has a thorough and large technique that allows her to handle virtuoso difficulties without apparent strain, and she has a lovely, dark tone that has a mature, noble aspect.

Lee joined the orchestra in the Cello Concerto in D (Hob.VII/2) of Haydn, in a mostly leisurely, genial reading of the work that stressed its lyricism. This was elegant listening, supremely accomplished technically, and Lee did her utmost in the second movement to evoke the movement’s passion, with the Boca Symphonia nicely holding back and letting her sing.

Schuller opened the second half of the concert with his own Concerto da Camera, written 40 years ago for the Eastman School, and prefaced it by asking the audience to “close your eyes and just listen” to the music rather than get distracted by watching the players tackle this gentle serialist score. And it’s a good piece, with jazz influences perhaps highly sublimated but undoubtedly still there.

This is not the kind of atonalism that accompanies randomness, but is an atonalism that is an exploration of other harmonic worlds from a clear narrative structure. The Symphonia did a fine job with it, giving the slow first movement’s crushed harmonies a Gil Evans kind of cool, and deftly handling the bubbly rhythms of the speedy second with careful attention to Schuller’s focus on instrumental color. – G. Stepanich

***

Gary Graffman (Jan. 15, Wold Performing Arts Center, Lynn University)

The eminent American pianist Gary Graffman lost his original career to focal dystonia of his right hand more than 30 years ago, but he has remained a champion of the small left-hand repertoire, especially that written by Erich Wolfgang Korngold.

In the second half of his recital Jan. 15 at the Wold Performing Arts Center at Lynn University, Graffman was joined by violinists Elmar Oliveira and Carol Cole, and cellist David Cole, for Korngold’s Suite for two violins, cello and piano left hand, written in 1930. Although it could have been an oddity, merely meant to add a novelty to an already unusual program, the Suite turns out to be nothing sort of a masterpiece.

And it was winningly played by the foursome on stage. On the first entrance of the fugue subject in first movement, the three string players carved out the subject in a bold and precise way that made the subsequent mutations easy to follow. The second-movement Waltz was delicious and sensuous, and the third-movement Groteske saw Graffman rattling off the opening bars with laudable precision and clarity. Cellist David Cole gave a powerful reading of this movement, which gives the cellist a strenuous workout.

Oliveira filled his spotlight turn in the fourth-movement Lied with huge, beautiful tone, and all four players gave the closing Rondo a joyous, athletic swing that demonstrated definitively that the group had been firing on all cylinders throughout. It’s hard to see why this piece shouldn’t be a chamber music staple for adventurous groups; Graffman and his partners made a marvelous case for it in this recital.

The Korngold occupied the second half of the program by Graffman, who filled the first with some of the more familiar left-hand repertoire, which as he points out is not large to begin with. The two Scriabin Op. 9 left-hand pieces were played with a big, warm sound, as was a left-hand arrangement of the composer’s celebrated C-sharp minor Etude (Op. 2, No. 1). It’s a fairly awkward piece to play in the original version, and it sounded a little labored here in Jay Reise’s recasting.

Carl Reinecke is little-remembered today despite his large output, but his C minor Sonata for piano, left hand (Op. 179), which has become a Graffman specialty, is an attractive and spotlessly crafted work.

This is a kind of writing that requires a much more Classic approach, and Graffman’s performance of it was a model of Haydnesque style, with the minuet in particular sparkling with a folkish verve, and the slow movement an essay in good tone production and interpretive restraint. Not a weighty piece, by Beethovenian standards, but an honest one, and Graffman does it good service.

The recital ended with the Brahms left-hand arrangement of the Chaconne in D minor from Bach’s Violin Partita No. 2 (BWV 1004). This is a monstrously difficult arrangement, and it, too, sounded heavy and hard to move at times. But Graffman has a keen sense of narrative arc and how to play it up, and he brought out the work’s breadth and majesty with great effectiveness. – G. Stepanich

***

The Links (Jan. 12, Stage West, Duncan Theatre, Lake Worth)

It sounded like a train exiting a long black tunnel, and it seemed to go on forever.

It was the sound of ‘Night, a piece by the American composer David Stock (b. 1939), and it was the harbinger of things to come: serial music, wittily played, as The Links trio opened its concert Jan. 12 at Stage West in the rear of the Duncan Theatre.

The three members of the trio – violinist Yuki Numata, cellist Joshua Roman and clarinetist Bill Kalinkos – are brilliant soloists all, but were sadly lacking in diction and stage presence when attempting to describe to the aged, silver-haired audience what the music had to say. Interestingly, there was little virtuoso playing from the clarinet. Violin and cello did most of the hard work until the last piece by Ingolf Dahl.

Noticing, a piece by Matthew Schreibeis (b. 1981) was given its second performance ever: Quiet passages were interrupted with violent outbursts from the violin. Coming Together, a musical joke by Derek Bermel (b. 1967), was all glissandos, a cacophony guaranteed to turn audiences away unless they got the joke. This audience did, with laughter all round when the players finished.

Cello and violin joined forces to end the first half with Ravel’s Sonata for Violin and Cello, written in 1922. This is a magnificent piece with a range of dissonant harmonies, grounded by sensitive playing from cellist Roman, ethereal in its loveliness. The military march of the last movement had echoes of the Swedish composer Dag Wiren, with violin and cello passing the theme back and forth.

Rogatio Gravis, by Sydney Hodkinson (b. 1934), tried hard to find its way in a mass of discordant warlike sounds with jagged interruptions, one instrument over another. This kind of composition has all been “said” before, and I found it tedious.

Saving the best for last, the Concerto a Tre by Ingolf Dahl had clarinetist Kalinkos earning his keep. From the opening bars, one knew this music had depth and structure worthy of Dahl’s teacher, Igor Stravinsky. The Links offered tight-knit playing, fine support of one another, and some lovely duets between cello and clarinet overlaid with sweet violin playing. – Rex Hearn