A very fine young cellist made an eloquent case Nov. 16 for an undeservedly neglected American concerto in the opening program of the South Florida Symphony’s concert season at the Crest Theatre in Delray Beach.

Clancy Newman, a first-prize Naumburg Foundation Competition winner and a graduate of Columbia and the Juilliard School, tackled the Cello Concerto of Samuel Barber (Op. 22), a distinguished, beautiful work, but one of a much more subtle musical language than his popular Violin Concerto.

Newman has a large, accurate technique, which is absolutely necessary for a work this difficult, and he made short work of the high-tessitura A-string calisthenics, spiccato arpeggios and frequent double and triple stops of the outer movements. But he might have been at his best in the slow movement, whose melancholy opening theme he played with an intense beauty, precisely marking out each note of the theme’s phrases for maximum eloquence. He has a dark, forceful sound that works exceptionally well in music with this kind of regretful character.

Aside from a couple flourishes at the end of the first movement that didn’t quite speak, this was a masterful performance at every important level, and one only wishes his appearance in town had been coupled with a solo recital so that audiences could further explore the range of his art.

Conductor Sebrina Maria Alfonso led her professionally staffed orchestra, now in its 16th season, through two other works, the Introduction and Allegro of Elgar, and the Schubert Ninth Symphony (in C, D. 944).

Alfonso has a good feel for English music, and this performance of the Elgar rolled along with the right kind of looseness in the thematic material that gives the piece its unusual character. The solo string work from the members of the symphony’s Blue Door String Quartet was capable and effective, but the tutti string ensemble was out of tune much of the time; it’s much more noticeable in writing like this, with its big unison lines, and the performance was hampered thereby.

The concert closed with a more than respectable rendition of the Schubert Ninth, with a noble, sturdy tempo for the first movement that broadcast the middle-of-the-road approach Alfonso took to the whole work. Some of the dance elements, particularly in the third movement, could have used much more spirit and verve; those catchy tunes he spins out, one right after the other, sound even better when they’ve got more snap and life.

It was a tight fit for the orchestra on the Crest Theatre stage, with room for only 60 people, and acoustically, the stage tends to swallow up the sound toward the back, so that much of the higher woodwind work in the Schubert was distant and difficult to hear. Overall, the orchestra sounded like an ensemble from the middle years of the last century, when such ensembles were generally smaller and not the overwhelming, high-gloss sound machines they are today.

That was all to the good, frankly, especially for the Barber, and it was a good evening of music making that deserved a much larger audience than the small house that showed up that Saturday night. Surely the word will begin to get out and the next concert, scheduled for Feb. 3 at the Crest and featuring pianist Christopher Taylor in the Prokofiev Third Concerto, will bring many more music fans to Delray Beach.

The other pieces on the Feb. 3 program are the Liszt symphonic poem Hamlet and the Symphony No. 10 (in E minor) of Dmitri Shostakovich. The concert begins at 7:30 p.m. Tickets start at $35. Call 954-522-8445 or visit www.southfloridasymphony.org.

Second-gig pressure no help to quartet

With nine seasons under its belt, the Delray String Quartet has achieved a measure of community profile for its concerts in three counties, and its recordings, the newest of which, a disc of Franck, Glazunov and Mahler, will be released sometime early next year.

Its first program of the 10th season, which I caught Nov. 10 at the Colony Hotel in Delray Beach, was to be followed immediately afterward by a fast dash down Interstate 95 so the group could play a night gig in Miami.

I think the imminent rush was too much on the minds of the players, because the playing bore strong signs of a rush to the exits. Then, too, the Delray chose to open its program with a Classical masterwork, the Hoffmeister Quartet of Mozart (No. 20 in D, K. 499), a genre that this foursome has not been able to master in any persuasive way except for some of the lighter Haydn quartets.

Just as every pianist who is easily fooled by the seeming simplicity of Mozart’s writing gets himself into trouble right away, the Delray lost its footing right from the beginning, with hit-and-miss ensemble and little sense of the subtlety of the movement, which ends in a whisper. The minuet movement was somewhat better, but the trio, while it has sudden sforzando accents and powerful trills, was played as though it were late Romantic music, with far too much force and drama.

The slow movement also missed the mark in that it requires space to breathe, and above for each note to have its full value. Without that, it starts to fall apart; what happened here is that it lurched from cadence to cadence without elegance. And the finale was far too fast for the precision the Delray was able to bring to the music, and sounded haphazard and unpolished.

Delray violist Richard Fleischman’s arrangement of the Romance (in E-flat, Op. 16) of Gerald Finzi, which came next, was much more satisfying. Fleischman has very skillfully reduced the music to quartet size, and the piece has the kind of soft, sweet Romanticism that this group specializes in and which its audiences seem most to enjoy. This is lovely, underappreciated music, and the quartet played it with feeling and taste.

The concert closed with a very hasty performance of the lone String Quartet (in E minor) of Giuseppe Verdi, which the operatic master composed in 1873 while waiting for work to resume on a production of Aïda in Naples. It’s a very fine piece, much underrated, and the Delray has programmed it before (it’s also on the group’s short list for the next recording).

But here again, the pressure of the impending deadline seems to have given the quartet a license to speed, so that after barreling through the mysterious opening music, the lovely, entirely Verdian second theme of the first movement became simply a place to slow down a bit, rather than a place where a strong contrasting structure could be erected.

The Andante movement, with its odd but ingratiating main theme, was heavy-footed rather than charming, and the tension of the contrasting music, which climaxes with a Verdi fingerprint — a rushing scale that rockets up and breaks off — sounded disconnected from the movement as a whole. The Prestissimo third movement, on the other had a rough energy that was attractive, and cellist Claudio Jaffé played the big tune of the trio with a generous singing tone.

The finale, however, a tricky fugue that presages the one that would end Falstaff, was messy, primarily because there was no way of finding the pulse, something that the slightest of accents on the third beat would have helped. But there was no denying the sheer impressive power of the music in spite of that, and the large audience in the Colony music room gave it rapturous acclaim.

I don’t think the second concert the quartet had to play that day did it in any favors for its first, and the performances betrayed that. With allowances made for the unreasonable pressure on the players in the Verdi, there remains the fact of its continued falling short in the works of the standard German repertory.

This is a group — excellent musicians, all — that needs to decide whether it wants to give the core Classical repertoire the extra hard work it requires in order to craft an admirable performance. It may be that its audiences can live without them, and prefer the Romantic repertory. But it seems to me that there are certain qualities of accuracy and ensemble that can only be truly achieved by a thorough acquaintance with the works that created the genre, and it’s that door through which this quartet will need to walk if it wants to keep reaching for that legendary higher level.

Cellist Jonah Kim joins the Delray String Quartet on its next two concerts, set for 7:30 p.m. Friday at All Saints Episcopal Church in Fort Lauderdale, and 4 p.m. Sunday at the Colony Hotel, Delray Beach. The program includes the String Quintet (in C, D. 956) of Schubert, Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 11 (in F minor, Op. 95, Serioso) and James Grant’s Waltz for Betz. Call 561-213-4138 or visit delraystringquartet.com.

Veteran chamber players get PBAU series off to graceful start

Patrick Clifford, a violinist and faculty member at Palm Beach Atlantic University, is the architect of PBAU’s Stringendo summer camp series, and last year began a new group of concerts at the school called the Distinguished Artists Series.

He opened the second season of the series Nov. 8 with a delightfully accomplished program of music by the members of the Palm Beach Chamber Music Festival, who came together a week before the third and final performance of their first fall season.

Concertgoers familiar with these musicians’ work at their summer festivals over the past 21 years would have recognized some of the pieces on the program, beginning with Fragments, by the American composer Robert Muczynski.

This brief five-movement wind trio (just 7 minutes long) is a favorite of flutist Karen Dixon, clarinetist Michael Forte, and bassoonist Michael Ellert, and they played it with the ease of long familiarity. This is witty, expertly crafted music for a rarely utilized ensemble, and the small audience at Persson Hall chuckled as they applauded, which is probably what the composer wanted.

The Muczynski was followed by the first movement of the early two-movement sonata for viola and cello known as the Eyeglasses Duo (WoO 32), which Beethoven apparently composed for two players with vision issues that he wished to make fun of. The success of his humor aside, this is a masterful piece, and violist Rebecca Diderrich and cellist Susan Moyer Bergeron, sporting a cast on her broken left foot, played it beautifully. It’s a piece with a great deal of inventive energy, and the two women were more than equal to the task.

Bassoonist Ellert returned to the stage in the company of pianist Lisa Leonard for the solo bassoon sonata of Paul Hindemith, whose death 50 years ago this month has been recognized with special performances across the musical community. This is a lovely little piece in two short movements, with the first having something of the flavor of a medieval chanson, and the second a taste of Debussy before moving on to a very Hindemithian march, and a return to the music of the first movement.

Ellert and Leonard took the first movement of the sonata quite slowly, making the most of its melodic contour, and the largely Romantic mood continued into the second movement. Ellert’s playing was warm and eloquent, and Leonard’s emphasis on Hindemith’s sweet side made for an unusually intimate, tender reading of the work.

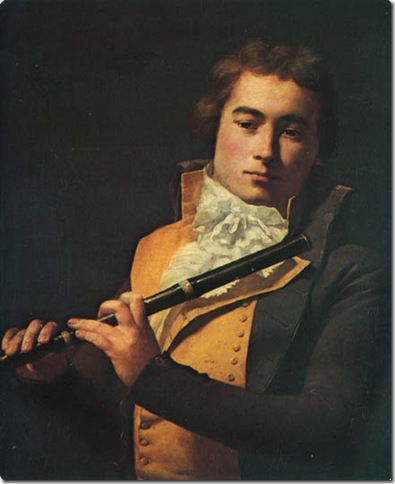

The second half of the concert opened with a rarity, a duet for flute and viola by the French Classicist Francois Devienne, a flutist and bassoonist best known for his concerti for those instruments. This Duo Concertante (in E minor, Op. 5, No. 1) turned out to be a charming, graceful work, beautifully idiomatic for both instruments.

Much of the music is a give-and-take between the two instruments, and the viola alternates chordal accompaniment patterns with muscular passagework of its own to counter that of the flute. It received a very fine performance from Dixon and Diderrich, who tossed off its frequent difficulties without losing the elegance of Devienne’s writing.

The concert closed with more Beethoven, this time the original version of the Op. 11 trio, which is for clarinet, cello and piano. Leonard was an important driving force here, stressing the surprising key changes that are essential to the structure of the first movement, while cellist Bergeron shone in the second movement with a commanding introduction of the pretty main theme.

The finale, a set of remarkable variations on Pria ch’io l’impegno, a tune from Joseph Weigl’s then-popular opera The Corsair, saw clarinetist Forte and his two musical partners deftly explore the sparkle and shock of Beethoven’s variations, and ably enough so that the listener was able to follow the transformations and not just hear the bursts of virtuosity that the composer made such an integral part of the music.

Clifford’s series this year includes some important guests, including the Chicago violinist Rachel Barton Pine (March 21). A bigger house would have been nice for the Nov. 8 concert, and here’s hoping the Distinguished Artists Series gets them as it grows.

The next concert in the series is set for Dec. 6 and features jazz trumpeter Wayne Bergeron. The concert starts at 7:30 p.m. in Persson Hall, and tickets are $20. Call 803-2970 for more information.

‘Virtual opera’ an interesting work in progress

Editor’s note: This review originally ran in the November print edition of Palm Beach ArtsPaper. It appears here for the first time online:

Few art forms regularly endure as much turmoil as opera, with its larger-than-life singers, conductors and stage directors, and its frequent financial problems, as witnessed by the bankruptcy in mid-October of one of America’s most important companies , the New York City Opera.

Sabrina Peña Young, a South Florida-born composer, has achieved something of a breakthrough in this regard, with a “virtual opera” she wrote and cast entirely through the Internet called Libertaria, a dystopic sci-fi machinima cartoon that premiered here on Oct. 5 to a small but brave audience at Calvary United Methodist Church in Lake Worth (disclosure: I conducted a pre-performance interview with Peña Young before the screening of the film).

Peña Young, a native of Cooper City who now lives in Buffalo, N.Y., is a percussionist by training, and studied at Palm Beach Atlantic University, Florida International University and the University of South Florida. She played all the keyboard parts for her opera, and created the bulk of the animation, using a variety of flexible technological applications to carry it out.

Her eight-person cast, most of whom she has never met, found out about the project through Facebook and other social media outlets, picked up their music and click tracks on Dropbox, recorded them and sent them back to Peña Young, who ultimately mixed more than 1,000 separate performances to get the sounds she wanted.

It was a heroic effort, and the level of singing in the animated opera was very high, especially from the women: Kate Sikora, Gracia Gillund, Gretchen Suarez-Peña, Jennifer Hermansky and Yvette Teel. The male voices were also impressive, with Broadway-like stylings from Matthew Meadows and more traditionally operatic work from Perry Cook and Joe Cameron.

So much for the clever way the opera was put together and realized. The work itself, running just under an hour concerns Libertaria, an orphan girl in a ruined postwar America of 2139 who finds herself fighting an evil system of genetic control and going on a personal quest to find her birth mother.

It sounds like a graphic novel, and it looks like one, especially with its cartoon balloons taking the place of supertitles. As a story, it is very much in line with the good-vs.-evil sci-fi tradition, with the added bonus of a plucky female heroine.

It is not unfair to say that the work appears unfinished in its current guise, with an ambiguous ending that hints at a sequel to continue the story. But it was fascinating to watch and to listen to, and Pena Young has included a wide variety of styles, from the swing of Metal Ink to the operatic balladry of I Will Never Leave You. There are a good many percussion effects in the opera, and its tone is primarily quite dark and sinister, very much along the lines of a contemporary video game score.

What it needs is more music, particularly a substantial ending tableau, and a couple more songs to explain character and motivation. As is, it doesn’t give the audience enough either of plot or music to make it wholly successful, but it still is a work in progress, and when Peña Young has finished her novelization of the story, surely more musical material will suggest itself to her.

It was in any case a highly laudable effort, and one hopes to see a revised, fuller version of the opera sometime soon, and in the long run, even one that’s done live in a theater.