Gustav Mahler is a composer whose vast constructs encourage interpretations that allow space for Mystery to inhabit some of his symphonies’ many rooms.

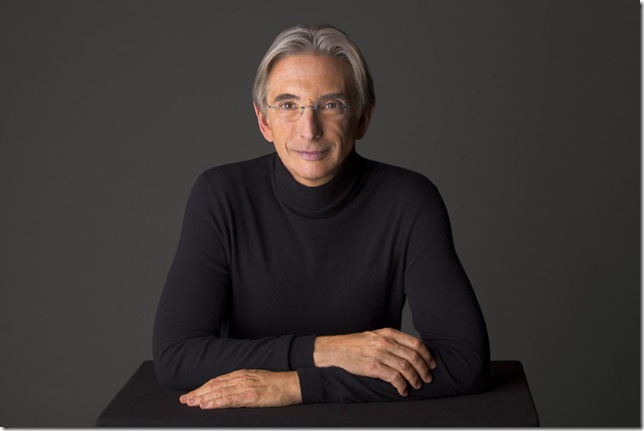

For Michael Tilson Thomas, the surface perplexities of Mahler’s Seventh can be likened to the jump-cut film styles of the German expressionist filmmakers Fritz Lang and F.W. Murnau, who would follow Mahler in the cultural space a couple decades later. And if you conduct the Seventh with an approach that burns all the fog off, a work of astonishing vigor and imaginative abundance is revealed.

On Saturday night at the New World Center in Miami Beach, conductor Tilson Thomas led his New World Symphony in two performances of the Seventh to end the orchestral academy’s 2013-14 season. As this was the last subscription concert of the season, that meant a farewell to a handful of the New World Fellows in the orchestra, whom Tilson Thomas acknowledged at the end of the concert, and to whom the full house granted generous and warm applause.

They had also been on their feet at the end of the Seventh, which received a high-energy, powerful reading. This was not a Mahler Seventh of wildly disparate grotesqueries from a late Romantic grab bag; this was a direct and intensely forceful performance that showcased splendid orchestral playing and the muscularity of Mahler’s writing.

Like all the New World performances I’ve heard over the years, there is a kind of force field of extra energy that can be felt infusing all the music, and in this symphony, Tilson Thomas unleashed it, particularly in the finale.

But the work began with a persuasively clear opening movement: Instead of murk and mystery in the introduction, there was a hushed but restless tension, with a big-toned baritone horn (played well by Kathryn Daugherty) announcing the central motif with weight and gravity. By the time the home key of E minor arrived with light-footed swiftness, a volcanic emotional landscape had made itself evident. The orchestra and its conductor made sure to mark the falling fifth in the second limb of the theme, which gives the melodic material direction and brought this extravagant music unity.

The first of the two Nachtmusik movements showcased some spectacular horn playing by Alexander Kienle, in his final appearance with the New World. His sound is enormous and golden, and his accuracy pinpoint; he knows how to make all the high notes Mahler writes come off as effortless. Hornist Anthony Delivanis, who played the “answering” horn, was every bit as good in his role. This movement’s character is somewhat elusive, but it does fit the idea that Mahler was trying to reflect the whole musical vernacular of his Vienna, and Tilson Thomas brought out the popular-song flavors of the movement expertly, particularly the big tune that rises from the depths and reaches its peak on a sweet sixth of the scale, Johann Strauss-style.

The Scherzo, which begins as a cousin to the Second Symphony’s rerun of Mahler’s song about St. Anthony’s sermon to the fishes, was taken at a brisk tempo, which had the music buzzing furiously, nicely exemplified by some good solo viola playing by Anthony Parce. The movement came off with a wry, parodistic feel, but without any of the ghostliness that has become a frequent interpretive choice: two wild outer movements, two intimate slower movements, and a murmuring, fragmented scherzo in the middle.

The second Nachtmusik, too, was lovingly and warmly played, and most attractive to listen to. Still, it would have been more interesting if Tilson Thomas’s approach had been to make a stronger contrast with it and the other movements. It would have been more effective to hear much wider dynamic variety, particularly in the softer passages, so that the delicacy of the guitar and mandolin, could really speak with the special color they bring to the proceedings.

But it was in the finale that this performance truly shone, with a tremendous, joyous energy that ran through every bar. Timpanist Alex Wadner, who had a starring role in the Scherzo, got things off to a blazing start, and trumpeter Alex Girard hit his concert high C with ease and authority (like Kienle, Wadner and Girard are from Oregon, and violist Parce is from Washington; looks like they’re growing good musicians out there in the Pacific Northwest).

The Die Meistersinger and Die Entführung references in this movement were marvelously played, and Tilson Thomas led a reading that a terrific sense of headlong, unstoppable strength. Commentators have snickered at Mahler’s own contention that the Seventh was the most cheerful of his works, but perhaps they hadn’t head a performance like this, one full of great good humor and high spirits, and one that at the same time demonstrated how much manic invention can be included in a symphony and still make perfectly lucid sense.