It’s been a big year for Nora Maité Nieves. Her first solo museum exhibition, Clouds in the Expanded Field (Nubes en el Paisaje Expandido), is currently showing at the Norton Museum of Art through July 7. The show is the climax of the two-month artist residency Nieves completed at the museum in January. A month later, in February, an animated version of her paintings aired on Times Square’s electronic billboards every midnight for three minutes.

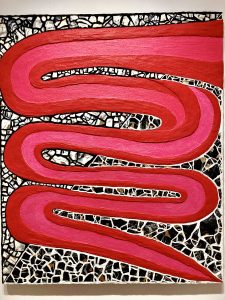

Nieves is now the first Puerto Rican artist to have an individual exhibition in the Norton’s galleries and her work projected on more than 90 monitors as part of New York City’s Midnight Moment initiative. Her technique entertains possibilities outside of the norm and challenges traditional notions of aesthetics. She sets out to stretch the skin of painting, bulk up the surface with multiple layers of texture, bright colors, and media including gold leaf, resin, and coarse pumice modeling paste. The resulting 14 works on display (five of which Nieves finished while in residency at the museum) are playful, dynamic, and inviting. They are dying to be touched, and experienced.

Heavily inspired by the domestic spaces Nieves experienced growing up, the works dance between abstraction and figuration and speak of home and belonging. Ornamental architectural patterns, colonial floor tiles, breeze blocks, and floor plans from places the artist lived in are recurrent motifs in her sculptural paintings. Having translated them into video, it was only a matter of time before Nieves — who holds a master of fine arts from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago — joined the 100-plus artists who have been part of the Midnight Moment, a digital public art program running since 2012.

Her stop-motion animation short Eyes of the Sea made a splash and introduced the masses to her inner world, where vivid memories and fantasy merge to bring about a message that is deeply personal and universal at once. In the spiraling video, just as in her paintings, Nieves makes sure to honor her roots while conveying her excitement about the future though bright hues and movement.

Back at home in Brooklyn and expecting the imminent arrival of twins, the artist spoke with Palm Beach ArtsPaper about the origin of her career and the experience of having her first solo museum show. During the hour, our conversation turns light and passionate, funny, and serious; it rushes and slows down, very much like the passing of clouds.

Congratulations on your first museum solo exhibition and the artist residency. I had a chance to see it when it first opened and felt such good happy vibes. I found it very playful. This chapter in your career must feel monumental. How would you describe this moment?

The invitation from a museum like the Norton was a surprise, in a way. I felt like all the hard work that I have been putting in through the years in my career led to this incredible honor. I’m not super young; like I’m not in my early 20s or 30s, but I feel like it came in the right moment. I have been very in sync with my work and there’s been a lot of growing and getting more mature. The opportunity came in this specific moment when I feel very ingrained into my work.

It sounds like you’re very grounded and are enjoying the maturity that comes from investing years into your work. Are you saying it would have been different had this happened earlier in your career?

Yeah, it would be different.

Let’s talk about the #MidnightMoment, which was done in conjunction with your solo show at the Norton and challenged you to step out of your usual discipline and re-interpret your paintings as video works. How did it feel to see your work Eyes of the Sea projected on that many monitors at Times Square?

That was mind-blowing. I never thought that would happen. I would have never even considered the space or trying something like that. It’s really thanks to Arden Sherman, the contemporary art curator at the Norton, who proposed me as an artist for this space. She really thought I could translate my paintings into a moving image. It was a lot of hard work, but it was great.

I’m always thinking about how I can make installations with paintings and make them bigger and occupy more space; finding this new medium felt like a way to push painting into a different direction. I took the challenge with a lot of fear. I wanted people to feel the texture in the video and I wasn’t sure if that was going to really happen, but I aimed for it.

They translate so well. It was such a stunning result.

The bad thing is that it was so fast; it’s only three minutes.

What reactions or comments did you get from your friends and strangers?

People were telling me it felt like being inside the painting. Some people said it mesmerized them, that they would look everywhere and find something different, and they wished it lasted a little bit longer. I think it went viral on Facebook in Puerto Rico. Puerto Ricans are very proud of this. Whenever one of us gets recognized…

It’s a win for everybody.

Exactly. So, I think I had my 15 minutes of fame.

I think it’s longer than that. Three minutes every midnight in February; that’s like 90 minutes.

Yeah, it was nice, very humbling. I never thought I would be occupying that space. I was stunned about the opportunity.

Take me back in time. Is there a particular moment or encounter growing up that sparked your interest in art? How did you come to this profession?

As a kid, I always liked to draw. All kids are creative during that time and look for a way to express themselves. When I was in fourth grade, I met this friend in my class and her dad was an artist. One day she invited me to her house and her dad came out wearing a painter’s hat and looking like the stereotypical classic idea of what an artist should look like. I was so impressed. When I went inside the house, it was full of paintings everywhere. They were by Andy Bueso and other artists. I loved the atmosphere and the colors. It was like magic.

It turns out Bueso had an art academy where he would teach art so, formally, I started taking drawing classes with him. That was my foundation. In 11th grade, I had the opportunity to attend Escuela Central de Artes Visuales, which is a famous high school specializing in the fine arts. On Saturdays, I would go back to Bueso’s studio to have support and guidance. Many friends who attended the same school, and from the neighborhood who took classes with him, somehow all returned to his studio when we were 17, 18 years old. This time it was different because he treated us more like peers. Unfortunately, I think he died in 2001; it was devastating.

It sounds like you were very focused early on and surrounded yourself with a strong support circle. You found a highly stimulating environment where you could grow, learn, and explore your voice. You are very lucky in that regard. Many artists don’t enjoy that kind of support early on.

Correct.

What artist, dead or alive, would you say has influenced your artistic voice aside from your first art teacher?

Mari Mater O’Neill, one of the most wonderful painters in Puerto Rico, pushed me to find my voice as a painter. Through the work of Ivelisse Jimenez, I found the spaces that live between colors. But when you look at works by these artists you might say, well, Nora is not painting like them. My work is not like theirs, it’s their wisdom and knowledge about painting that I took from them. There’s also Ana Mendieta; she is an artist who makes you think about what art can be and the importance of the human presence in the work.

Donald Judd and Eva Hesse were also big influences. Even though you might not think of them when you see my paintings, for me these artists made me think of breaking the boundaries of painting and the importance of removing or adding yourself in the work. Judd would be like removing the artist, and industrializing the process, like an assembly-line kind of painting. Hesse is about achieving the most reduced minimal form that is still full of one’s touch and humanness.

Sometimes that is precisely the lesson you extract. It’s not so much the aesthetic, but the other information you get from other artists’ evolution, and journey.

Exactly. I’m interested in form and tridimensionality and material. Sometimes, I want it to break out of the wall. Sometimes, I want it to be a sculpture. But I also want it to feel very personal and open and make you think about memories; how our memories are our identity and not always attached to the place where we are born. Identity is something that evolves as we experience life. As things get attached to us, we become a collage of things. My paintings are trying to be three-dimensional collages.

To me, they resemble sculptures more than paintings. They have all these layers of materials and texture, which bring them to life. They have such a physicality to them, such a presence. They are not just pretty to look at. I was wondering how you developed your current artistic aesthetic or painting language.

I’ve realized that I like to imitate things. If I see a texture on the wall, I start thinking about emulating that texture with painting materials. If I want to create the sensation of tiles, I don’t want to buy them but recreate them using painting materials. The materials depend on what I want to represent and imitate. Sometimes, I would like to be more reduced, but I’m starting to accept that I’m also a maximalist. I like to add and add and add. I accept myself and the way I create. These are the things that I feel I can explain now that I’m feeling more mature.

Among my favorite pieces in the show are Snake Dream and Garden of Eden. They are probably the most minimalist in the gallery, but I like their simplicity. And that’s why reading the list of materials you used in these works surprised me. There’s so much to them. That was an interesting discovery. What’s the most unusual material you have ever used in your work?

For that green that looks like grass in Garden of Eden I used this new material called kaolin, which is a kind of plate-like ceramic. I got it at Guerra Paint, a store that’s very close to my studio in Brooklyn. I saw it and I was like, oh what is that? It has this soft dry quality, which makes sense because it’s like clay dust, but it also makes me think of eyeshadow. I find makeup very seductive.

From the beginning of my career, I always wanted to seduce the viewer. I wanted to make painting an object of desire, so I started using glossy materials, which made the paintings look like candies and dessert, very edible. I feel that I have continued that objective.

I understand the name of your solo exhibition at the Norton, Clouds in the Expanded Field, was born precisely out of this interest you had in painting in the expanded field or stretching the skin of painting, in a way. Do you ever feel tempted to define this in-between of sculpture and painting that your works are suspended in, or do you prefer that they remain forever evolving, and unrestricted like clouds?

I like to be in the in-between. There’s something about the tension, being between two disciplines, that creates an open conversation. Things don’t have to be just one thing.

Sometimes it’s a little bit of a problem because galleries want you to make just a certain type of painting and stick to a certain style and think about the market. But I like to work many ways. That’s who I am.

I was going to ask you about that. It’s no secret that this profession is not for the faint of heart. There are easier life paths than being an artist and making a living from art. Skills and talent aside, I imagine your success is partially due to your ability to promote and market yourself. How do you balance the business side of things — the commercial aspect of being an artist — with your creative side?

I have always been someone with a strong conviction. That has closed doors and opened others. Different people will want different things from you; you must know yourself, know what you want, trust your aesthetic, and push through. That might take you on a longer road, but it’s OK to not travel on the fast one. When an institution recognizes an artist, it validates the work on a different level. An invitation like this solo show tells me that it’s ok to be strong in my way of thinking.

If I hear you correctly, in this journey, there’s always a danger of compromising your artistic authenticity or freedom for the sake of recognition or to conform to societal norms. And the way to protect yourself from that is getting to know yourself.

I would say so. Yes. In the end, there are going be people who think like you, but first they must find you. It’s hard. For example, with this show, it was very nice to have people write to me telling me how amazing it was for them to find artworks made by someone like me in the museum, to see themselves represented. It gave them hope there might be a space for them too.

You spoke of memories earlier. I know you are originally from San Juan, Puerto Rico, and I can tell that the designs and symbols showcased in your work, like the ones resembling ceramic floor tiles and concrete blocks, are personal. There’s something universal about recalling memories to create something new. Judging by the energy and positivity your show exudes, I’m going to guess that yours are happy, fond memories. Do you mind sharing one of them?

Actually, my work comes from painful memories of struggle as a family. My parents divorced when I was nine years old, and it was a very difficult divorce. My mother, my brother, and I started the journey of living like nomads. We moved so much, from house to house, and for many reasons. Sometimes, my mother couldn’t afford it anymore and we would be kicked out. These houses we rented, sometimes the aesthetic wasn’t the best. Sometimes, the bathroom would have different patches of tiles. A room would have this tile on one half and another set of tiles on the other half. I always found it so ugly.

As an older person finding myself and my voice, I realized that I had a lack of ownership to space and the things that I found ugly or difficult while growing up also made these places special and beautiful. I want to embrace that. I want to take ownership of these memories and these places that I didn’t own. These places that made me stronger, and who I am now. I want to find that ownership and that sense of belonging in my paintings. I don’t work on them from a place of trauma. I don’t look back with sadness. I think that’s why they have such good energy.

I think there’s a beauty in the process you just described, and it sounds like you have found that beauty.

Yes. I almost never talk about it, you know, where things come from, but I embrace them. I try to connect with people in a way that makes them think about their memories, and their sense of belonging. Maybe they had a similar experience like mine or maybe not.

I remember I did this workshop in a museum in Puerto Rico some years ago where I invited the people to draw the floor plan of their first home from memory. Whatever they could remember. I just didn’t realize that I opened a door to a space that I wasn’t ready to manage as an artist in a workshop. It was very sensitive, and emotional and I was like Oh God, how do I put the genie back in the bottle? But it was very beautiful. For some, it brought a lot of nostalgia. For others, it brought happy memories. There was a kid in the class who drew the house he wanted to live in the future. I took that experience with me.

After the pandemic, I wanted to start bringing my imagination into my work. Elements like the snake plant started to take on the air of a character. I didn’t want to rely on floor plans of specific spaces but imagine new spaces that don’t exist. This show has a little bit of of all this journey and this new place I feel I’m entering, which is with more imagination. There’s more fantasy now.

Most artists have a particular routine that gets them in the right mindset to create. Some play a certain type of music or choose a particular time of the day or drink tea. Is there a particular ritual that gets you in the creative mood?

I like to get to the studio and have some coffee.

My process starts with drawing. I need to have an idea of what I’m going to work on. Because of how I paint, and the many layers involved, I kind of have to know where to start.

Do you ever encounter a creative block in your artistic practice? How do you overcome it?

Sometimes I try many things and the painting is still not working and I feel like this is a failure. When that happens, I have to step out or draw or move into something else because I’m waiting to find a bold move. Something drastic. Something that cancels a lot of what I did and takes it into a new direction. I call it a bold move.

That sounds painful. After investing so much time in one direction, to have to undo it and take a completely different path, that’s brave.

Yes. That black triangle in the painting called Mirror Rooms was a bold move. A lot of the tiles that I painted black and green were part of that bold move because the painting was not working at all. I still wonder if it’s working. But that decision, that black triangle that canceled my previous ideas, felt like a I-need-to-do-this moment. It’s strange and weird but I had to do it.

Another example is the large-cloud painting. The first layer of paint was matte, and it wasn’t working. I felt so frustrated because it’s the biggest painting in the show, and it felt so dead. At that scale I felt it had to be glossy. I went and repainted it with a gloss medium and then it worked, and the painting moved differently. But I felt very scared. There are some paintings that come with a lot of struggles.

If I showed you the sketch that I made for that painting Mar y Tierra, Noche y Dia … it’s completely different. I suffered so much with that painting. But at the end, it all comes together. Sometimes I don’t even know how I got there.

Well, the suffering paid off for sure.

Yes.

If you could have visitors walking away with one impression of the show, what would that be?

If they are painters, I hope they go back to the studio and start painting. I hope it motivates them.

From everyone else, I want them to feel that they can be part of the works and be immersed in them and step inside of them.

You are not the first person to tell me that they feel a good vibe, and happy and motivated after the show. I like that because the work is about life, and it should make you appreciate being alive in these times.

What’s next for Nora Maité Nieves? Any upcoming projects or exhibitions you’re looking forward to?

I have a piece right now in a group show called Entre Horizontes at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. It’s closing on May 5th. But right now, I’m eight months pregnant with twins so I’m nesting, taking a break. The belly is so very heavy; there’s not much I can do right now. I’ll be delivering probably by the end of April. I have drawing materials at home and will probably be back in the studio in July or August. My plan is to draw whenever I have energy and time. But I don’t know how this is going to be. I have never done this, it’s something very new.

Congratulations on that account. That makes this conversation even more meaningful. You should enjoy this moment. You’re about to embark on a whole new journey.

That’s true and I feel like there’s a little bit of this journey in the show. You know, thinking about the beginning of life, and the genesis of things. Garden of Eden conveys a little bit of that, the beginning of things. It’s been very special. I’m overwhelmed with joy, and at the same time, with fear in the sense that I’m getting into something very new, and I will have to find myself again.

You have proven you are absolutely equipped to do that. I am sure that motherhood is going to provide even more inspiration and memories and you’ll be back in no time producing great work.

Thank you so much.

Thank YOU. It’s been a pleasure.

If you go

Nora Maité Nieves: Clouds in the Expanded Field is on view through July 7 at the Norton Museum of Art, 1450 S. Dixie Highway, West Palm Beach. Hours: Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.; Friday, 10 a.m. to 10 p.m., Sunday, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Closed Wednesdays. Admission: $18 adults, $15 seniors, students, $5, children 12 and under, free. Call 561-832-5196 or visit www.norton.org.