To the large crowd that attended his recent talk while still holding their magnifying glasses, Norton Museum curator Jerry Dobrick said the museum was incredibly lucky. And he was not talking about a large monetary donation.

Dobrick, the museum’s curatorial associate for European art, was referring to the 43 works by old and modern masters that make up Master Prints: Dürer to Matisse. With names like Rembrandt van Rijn, Francisco de Goya, Pablo Picasso and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, the exhibition naturally had everyone’s attention the minute it opened Nov. 6. It runs through Feb. 15 and will not be seen anywhere else to allow the works to rest and prevent fading. They should not be exposed to light for more than three months.

“If we wanted a print show to travel, we would have to change out the selection on view and then it would become a completely different show,” explained Dobrick via e-mail.

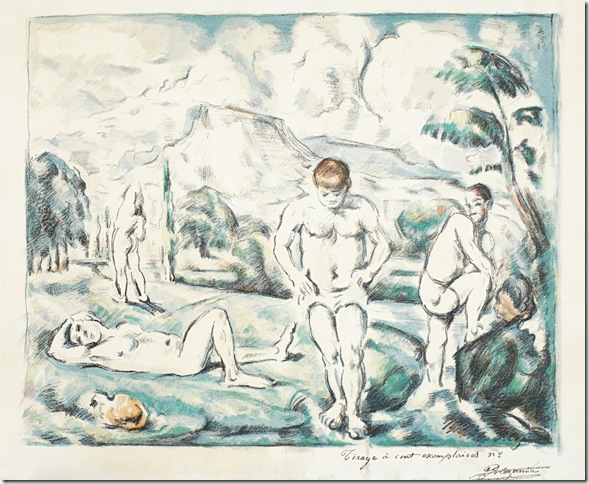

Represented through etchings, woodcuts, lithographs and engravings exploring erotic, classical and romantic themes, are 500 years of the printmaking process — with the earliest work dating to 1460.

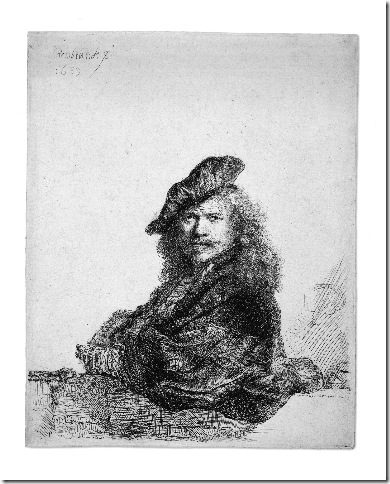

The magnifying glasses are for a closer look at the details and are needed immediately upon entering the darkly painted first room. Rembrandt, sporting Renaissance clothes, confidently looks at us from his controlled pose in Self-Portrait Leaning on a Stone Still (1639). This is one of seven works by him in the exhibition. Note the wrinkles on his forehead and the volume of his rope, where the ink is also richer and darker than in other areas, such as the hair.

It is as if Rembrandt knew that, centuries later, viewers from all over the world would come to see him and he wanted to look good. This captivating print emerged from a delicate process involving acid and varnish and carried a personal statement. Rembrandt asks to be thought of as an equal to the masters who came before him.

He would have been pleased that the museum chose this image to be blown up and greet everyone from Dixie Highway. It is one of 11 self-portraits known to exist; the other 10 from this particular print are in museum collections.

Speaking on this “incredibly rare” etching, Dobrick said: “As far as I know, it’s the only print in private hands still.” Other prints of this caliber are already owned by museums, he said.

A humble Rembrandt self-portrait, less concerned with fame and status, came nine years later. Look for it in the show.

On the opposite side of Leaning on a Stone Still hang Picasso’s Faun Unveiling a Sleeping Girl and the piece that inspired it: Jupiter and Antiope by Rembrandt. Picasso’s 1939 aquatint depicts a satyr, which is Jupiter in disguise, visiting Antiope, the daughter of the King of Thebes. The beast kneeling on one leg lifts the sheets covering the princess’ voluptuous nudity. The light bathes her body while her face remains in shadows. She still sleeps or pretends to be doing so.

Its 1659 etching companion gives Antiope a more dramatic sleeping pose while the Rembrandt-resembling Jupiter stares at her with lust. This is considered the most erotic etching of his period.

Another Rembrandt etching presents a surprisingly light, seemingly incomplete action scene packed with intensity and drama. In The Large Lion Hunt (1641), figures appear twisted, swords are drawn and horses have fallen to the ground taking with them soldiers who refuse to give up. It is a similar dynamic to that in Leonardo da Vinci’s The Battle of Anghiari.

“This is the first instance in which an engraver gives credit to the person who created the design,” Dobrick said, referring to Man Climbing the Bank of a River.

Marcantonio Raimondi’s 1509 engraving reflects the artist’s tendency to copy other artists; an ability he was known for. This work is based on a fragment of Michelangelo’s Battle of Cascina fresco, which was never finished. The writing on the lower right acknowledges Michelangelo while taking credit for the print creation. Raimondi honors the muscularity Michelangelo gave his figures, which is seen here on the man’s backside, and makes it his own.

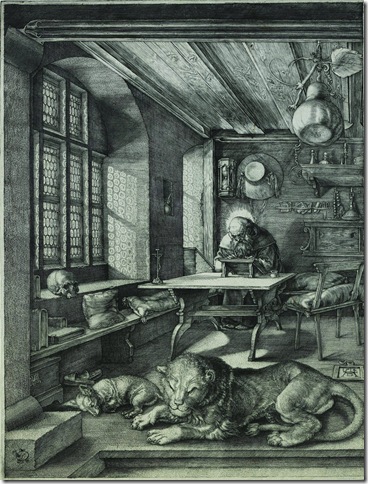

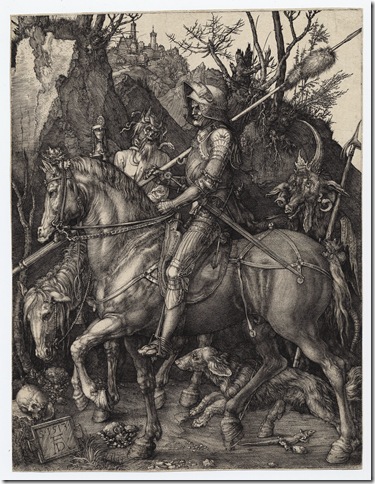

In 1513 and 1514, Albrecht Dürer engraved three copper plates that came to be known as his Meisterstiche (master prints) for their supreme quality. Two of them are in the show.

In St. Jerome in his Study, the German artist pushes the limits of a two-dimensional surface and creates a striking living space with a silvery tone and brilliant whites, as seen on the halo. Dürer, who trained as a metalworker, surrounds the saint figure with several of his attributes: the lion sitting by the steps, the skull by the window and the cardinal’s hat on the wall. One can sense he won’t be easily distracted.

An hourglass is seen above his head and appears again in Knight, Death and the Devil, as a symbol of mortality. This focuses on a knight’s unshaken determination to continue riding forward despite having Death and the pig-faced Devil close by. As in his 1504 Adam and Eve engraving, much attention was given to the animals, the background landscape and the vegetation.

Because even the best senseis can be followed by other best senseis, the exhibition gives us a second room to admire more masterpieces, such as Goya’s Spanish Entertainment from the Bulls of Bordeaux (1825).

This lithograph was created a year after the artist’s relocation to the Bordeaux region due to health reasons. In it, Goya captures a lively and dramatic encounter between five bulls and a crowd. Not all ends well. An unlucky bystander who has fallen to the ground suffers at the feet of a dark bull seen in the foreground. Meanwhile, four bulls appear at the center surrounded by a human ring that appears more menacing than the actual animals. Goya seems to suggest that the people, not the beasts, ought to be feared.

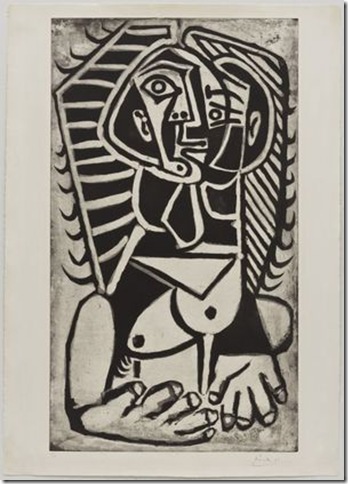

The room also houses more of Picasso, with his The Egyptian (1953) taking the prize for most lively viewer reactions. Maybe it has to do with the broad blocks of contrasting whites and blacks. This aquatint portrays Françoise Gilot, the mother of the artist’s children and the subject of many of his works. Her hands and breasts are minimally treated and kept very basic compared to the intricate structure of the woman’s head, particularly her hairstyle, which the title traces back to.

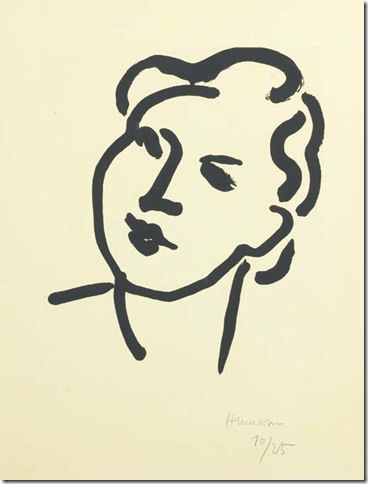

Bold black strokes give form to a woman’s wavy hair and full lips, which in turn lend a romantic, soft touch to Henri Matisse’s Nadia with a Round Face (1948). Although similarly minimalist to the adjacent Joan Miró piece, Nadia is freer and much less constrained.

The exhibition feels intimate and special. One senses opportunities like this one are not abundant, but do try and resist the temptation of rushing through it for the sake of claiming to have seen it. An excruciating amount of detail went to each of the 43 works displayed and each deserves some contemplation. All cannot be realistically captured, which is to say this is not just a not-to-be-missed show, but one to be revisited a couple of times.

Master Prints: Durer to Matisse runs through Feb. 15 at the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach. Admission: $12 adults; $5 ages 13-21. Hours: 10 am-5 pm Tuesdays-Saturdays except Thursday, 10 am-9 pm; 11 am-5 pm Sundays; closed Mondays. For more information, call 561-832-5196 or visit www.norton.org.