The Norton Museum has an expanding collection of contemporary art, and, like many museums that evolve and grow from their initial purpose, it does not have a permanent exhibit space for it.

Although significant, it would be difficult to justify replacing any of Ralph and Elizabeth Norton’s original collection, or changing the focus of current gallery space, and the museum already underwent a significant expansion in 2003 with the addition of the Nessel Wing (Oh, that every museum should have such troubles as what to do with so many great donated works). The temporary solution: biannual exhibits providing a peek at some wonderful — yet otherwise hibernating — gems.

This is the case with Here Comes the Sun: Warhol and Art After 1960. The exhibit showcases 40 works by significant contemporary masters that include paintings, drawings, and sculpture. The Norton’s curator for contemporary art, Cheryl Brutvan, has organized the exhibit chronologically, providing a microcosm of an explosive period in the evolution of art when the very nature of art itself was questioned, tossed in the trash, and made over on completely different terms. Then its old self begin to emerge again through the cracks.

Some might argue that it’s been the most exciting period in the history of art because during this time the epicenter of the art world moved from Europe to our own backyard. Although merely a glimpse, many of the artists that ushered, or partook, in revolutionary post-modern movements, beginning with Andy Warhol, are here. Donald Sultan, Keith Haring, Helen Frankenthaler, Robert Rauschenberg, and Joan Mitchell all make an appearance to remind one of the resounding triumph of post-World War II American art.

Actually, it’s a shame these works aren’t on permanent view. Many are stunning, such as Donald Sultan’s The Granary (1988), a massive concoction of tar and acrylic paint. They epitomize the radical shift that engulfed the art world and brought us to where we stand now. Although vastly different in style and medium, the unifying element is that these works were completed when the definition of art was challenged, the future of the paintbrush was questionable, and conceptual thought trumped artistic mastery.

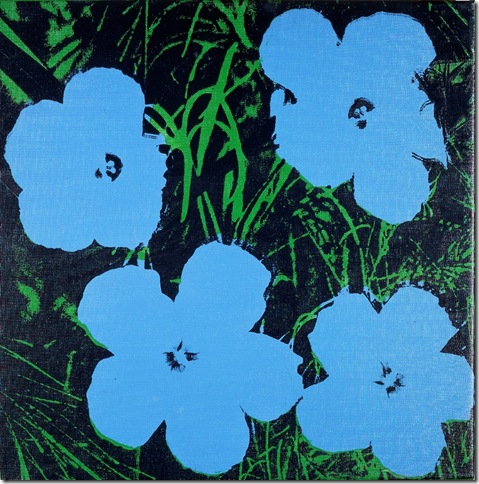

Warhol, viewed by many as the messiah of post-modernism, and the man who married the fine arts and consumerism, rightly has his own wall at the entrance. The exhibit features his omnipresent Four Jackies (1964-1965), which depicts four images of the first lady. Then there is an assemblage of the Campbell’s soup cans that propelled Warhol to superstar status and marred the line between artist and celebrity. And it’s interesting to view Flowers (1964), the work that gave rise to issues regarding appropriation in art and resulted in a lawsuit from the original photographer, as well as referencing the hippie movement’s flower-child ideology.

There are four sculptures in the exhibit by Sol LeWitt, Anthony Caro, Nancy Graves, and Harry Bertoia that follow along on the progression procession. The Italian-born Bertoia’s minimalist Sunburst III (1968) stands delightfully near the exhibit’s entrance, seemingly inviting one to blow on it and make a wish. Then there’s Chilean-born sociopolitical artist Alfredo Jaar’s Untitled (Water) (1991-1994), which utilizes a light box and color transparencies to make a statement about reality and representation, and provides a hybrid of sculpture and photography.

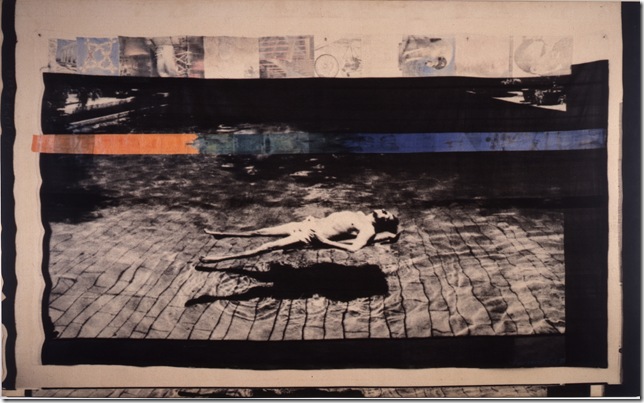

Continuing with the hybrid theme, a large painting produced by Gianfranco Gorgoni and Robert Rauschenberg provides a witty glimpse into Raushchenberg’s day-to-day existence. Italian photographer Gorgoni came arrived in New York in 1968 to photograph and chronicle New York artists. There he befriended Rauschenberg. He captures the artist leisurely floating in his pool in Robert Rauschenberg, Captiva, Florida (1988). The image is hard to shake from the mind afterwards because of the intimate glimpse into Rauschenberg’s private world.

Moving from Rauschenberg to the aforementioned Sultan and Philip Pearlstein’s Untitled (1966), one views a mini-series on the reemergence of the “painterly” painters, those artists who seem inspired by the sheer physicality of the medium of paint and who gained momentum in the 1980s. Even after painting had been pronounced dead on multiple occasions, these “necrophiliacs” confirmed that the reports of death were, at best, greatly exaggerated.

It’s reassuring that the exhibit culminates with a work by Jacqueline Humphries. Her presence confirms that the Norton’s contemporary focus has merely just begun. The large, lyrically assaultive abstract painting Untitled (2009) inspires, and illustrates the beginning of an ever-evolving journey. Humphries’ work infuses abstraction with something fresh.

“The objective is to knit wildly varying perspectives into a unified space,” the artist has said. “Because of the way light reacts to the metallic paint, the paintings change as your physical relationship to them changes.”

Here Comes the Sun also knits “wildly varying perspectives into a unified space” with a procession of works primarily by American artists who leapfrog off of one another’s breakthroughs — and a few surprises thrown in, such as Picasso’s Harem Scene (1968). Although it’s a Cliff Notes version of the past 50 years, it’s impactful and it establishes the Norton’s commitment to contemporary art, which, hopefully, someday will have a permanent space.

Jenifer A. Vogt is a marketing communications professional and resident of Boca Raton. She’s been enamored with American painting for the past 20 years.

Here Comes the Sun: Warhol and Art after 1960 in the Norton Collection is on view at the Norton Museum of Art until May 2. Hours for this exhibition are Tuesday through Saturday from 10 a.m. until 5 p.m., and Sunday from 1 p.m. until 5 p.m. Admission is $12 for adults, $5 for visitors aged 13 through 2, and free for children under 13. For more information, call 561-832-5196, or visit www.norton.org.