If New Yorkers won’t come to New York, the city will come to them, in the form oil paintings, watercolors and oil pastels with impressionist, cubist and realist tones.

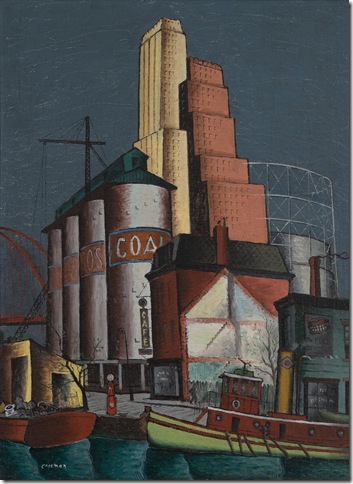

A rich selection of works depicting the pros and cons of the booming city makes up Industrial Sublime, which opened March 20 at the Norton Museum. The gallery rooms are filled with cityscapes by famous and less-known painters who found factories, roads and bridges to be the new Nature.

One of the first works we encounter is a 1910 piece titled The Bridge: Nocturne (Nocturne: Queensborough Bridge) by Julian Alden Weir. Its muted colors establish a moody atmosphere that is occasionally interrupted by city lights, which are represented as short thick-paint brushstrokes. As other paintings in the exhibit, it is best to look at Nocturne from a distance; in this case, to better observe the relationship between electricity and the city’s skyline. It was time to kiss the stars goodbye.

A similar dialogue exists in an enchanting watercolor from 1940 by Marguerite Ohman. View of the East River at Night with Queensborough Bridge, New York City shows us a night scene filled with sparkling lights. Bold black lines give this fairytale of a picture an edgier look.

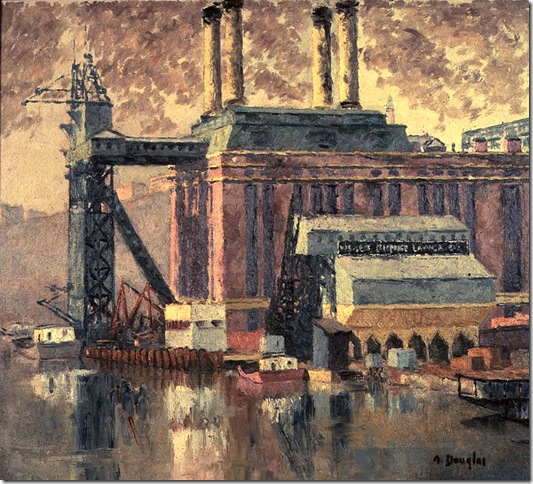

As city lights, smoke was another symbol of modern times and one sees it in many works here. The most striking example is Roundhouses at High Bridge by George Luks, where smoke columns extend dramatically all the way up to the edge of the canvas. As aggressive and urgent as these smoke pillars are, Luks makes room for softness and adds a quieter, rosy sky.

A touch of red draws us near the actual building, which is darkened and hard to discern. The piece is a panoramic view of the roundhouse and rail yard at 170th Street as well as the Harlem River. Arnold Hoffman’s Untitled (Weehawken) is equally smoky and exaggerated but the color choice less dramatic.

One can tell the artists had fun adding the human touch.

Take Richard Hayley Lever’s 1913 High Bridge Over the Harlem River where a line of diminutive heads appears above the bridge railing resembling a line of ants. The massive size of the bridge emphasizes the miniature people although the structure does try to disrupt nature as little as possible. Greens and blues are still visible under its arches.

A similar case of shrunken peeps comes with John Noble’s 1937 The Building of Tidewater where gigantic red pipes sit still, by the shore, as if waiting for the perfect moment to devour a group of tiny workers. The colors here are striking and the water and sky beautifully painted. It is hard to believe we are looking at a construction site (a new refinery for the Tidewater Oil Company).

We find a closer, more realistic approach to human figures in George Parker’s East River, NYC where two workers take a break by the docks. It is a cloudy day. While the men concentrate on lighting a cigarette, seagulls are flying barely above the water while others fly over the ships. The city buildings in the background seem less accessible with the excessive steam and smoke almost acting as barrier.

Sharp structures, bridges and tall skyscrapers are not thought of as warm subjects. In fact, most artists here are known for grim straightforward depictions of urban life. But even with a mechanized world serving as inspiration, many works come across as tender and kind.

Purple patches of color portray the steam emanating from boats in Jonas Lie’s Afterglow. The Norwegian-born artist’s take on the city is magical and a great study on color and the use of light. Electrical power, again, is now part of the landscape and a symbol of hands at work. Office buildings and skyscrapers sit there, as an illusion or a dream that can be reached as long as one first swims in what looks like very cold waters. Lie taunts us again with the distant yet obtainable goal in his Path of Gold painting depicting tugs navigating away from us.

This last scene shares a similarity with Lower Manhattan which comes later in the exhibition and also features steamboats moving away from us toward the tall concrete horizon. The body of water separating the city and the boats delicately changes colors as the sunlight hits. The narrow, vertical canvas along with the flattened quality and color choice reminds me of Japanese prints. This work is by Ukrainian-born Louis Lozowick.

More than 60 pieces celebrating the energy, vitality and cruelty of New York are included in Industrial Sublime, which runs through June 22. To discuss them all would leave you with no surprises — and leave me exhausted. You will need a good hour, if not more, to take it all in. I spent two and still could have used more time with Robert Henri’s gloomy East River Embankment, Winter. It’s the least colorful of all the works and presents us with a cold, damp waterfront scene.

More than half of the canvas is left practically empty and Henri’s restricted color palette is unexpected. Instead of having color draw our attention it is the absence of it that stops us on our tracks; especially having seen a contrasting piece by him (Cumulus Clouds, East River) earlier in the show. Both are not to be missed.

For a Van Gogh-like interpretation by an American artist, refer to Reynolds Beal’s 1930 Poughkeepsie Railroad Bridge. The combination of bright colors, thick paint and compulsive repetitive strokes is a bit overwhelming, but you can definitely spot the European influence. The only Georgia O’Keeffe in the show comes in the form of a charcoal drawing titled East River. Sorry, no sensual flowers here.

However, there is plenty of nature around. The show provides a modern example with Van Dearing Perrine’s 1906 Palisades. The dramatic ledge of rocks takes over most of the canvas and threatens to advance forward. A line of trees is left begging at the base, but they are insignificant next to the rocks’ commanding presence, which receives the sun’s blessing.

Among my favorite pieces is The Bridge Pier by Robert Ryland. Painted in 1931 during the Great Depression, this is perhaps the hardest image to look at. A man sits on a pier contemplating the once-obtainable dream, which now appears distant, colorless and harsh. For such a crowded dynamic city, this scene only speaks of silence and solitude. The man is wearing a white shirt and his face is turned away from us, but we can guess the expression is one of disappointment and surrender.

Industrial Sublime: Modernism and the Transformation of New York’s Rivers, 1900-1940 runs through June 22 at the Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach. Admission: $12 adults; $5 ages 13-21. Hours: 10 am-5 pm Tuesdays-Saturdays except Thursday, 10 am-9 pm; 11 am-5 pm Sundays; closed Mondays. For more information, call 561-832-5196 or visit www.norton.org.