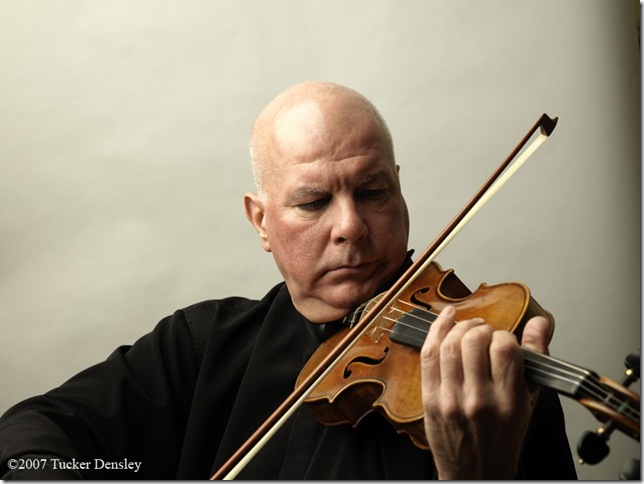

The American violinist Elmar Oliveira, gold medal winner at the Tchaikovsky Competition in Russia in 1978, has been assiduously working on raising his local profile in the past several years, having made a mark for himself on the national and international scenes since then.

A part-time resident of Jensen Beach and a teacher at Lynn University in Boca Raton, he has made several appearances with the school orchestra and given recitals, recorded the Schumann Violin Concerto with the Atlantic Classical Orchestra for his own Artek record label, and last month launched a string group at Lynn called the Golden Rule Ensemble.

All those appearances give local audiences a chance to see a very fine violinist of an older generation, but one not content to rest on his achievements, and as he showed in an appearance Sunday with The Symphonia Boca Raton, someone who can still find something exciting to say with one of the standard works of the repertoire.

Also notable at the concert in the Roberts Theater on the campus of St. Andrew’s School in western Boca was that it was under the direction of James Judd, leader of the much-missed Florida Philharmonic and a musician local audiences always welcome to the podium. In addition to the Beethoven Violin Concerto (in D, Op. 61), Judd led the orchestra in the Serenade for Strings (Op. 1) of Samuel Barber and the Surprise Symphony (No. 94 in G, Hob. I: 94) of Joseph Haydn.

The Barber, drawn from a string quartet the 18-year-old composer wrote while studying at the Curtis Institute, has much of the mature Barber in embryo: A natural, dark lyricism, and a rich harmonic sense in which chords and contrapuntal lines are often bitter and uncompromising, but always couched in a tonal framework.

Ensemble was a little shaky at the outset, but ultimately the strings gave a good account of this interesting, too-little-played music. The second and third movements in particular have an almost English feel to them, something along the lines of Arnold Bax or Gustav Holst, something Judd, an Englishman himself, perhaps found congenial. He led with large, enthusiastic gestures, encouraging his musicians to engage themselves, and he and the Symphonia made a strong case for Barber.

The Haydn symphony is the composer’s best-known work in this genre, and his symphonies make ideal programming choices for chamber orchestras of this size. This was a rather ordinary performance of the symphony, with plenty of carefully judged effects but not a lot of internal fire or exploration of the composer’s wit.

In the first movement, for instance, the sliding cello line in the introduction went by without bringing out any mystery, and the movement itself was good and strong but not particularly crisp. The famous surprise chord of the second movement was suitably powerful, but somehow too heavy, though the softness the orchestra exhibited to begin the movement was impressive. Still, while the C minor entrance was dramatic and attention-getting, the big harmonic frieze that follows could have used wider horizons, a more expansive touch.

Accents were strong and dance-like for the Minuet, but if it had lifted better on the third beats, there would have been more of a rural celebration feel, which seems to me central to the music of a country boy like Haydn. Bassoon work in the trio was admirable, but the ending of the movement was not together. The finale was fleet of foot and charming, but didn’t really hit its stride until the final pages, when the high spirits that had been intermittent throughout the work at last took hold and drove the music to a joyful conclusion.

The second half was given over to the Beethoven, an unusual placement for a concerto, but a very wise choice for this particular concert. It was the central draw, and Oliveira and the orchestra did not disappoint.

Oliveira is a player with a forceful, powerful sound, a sound that projects no matter what he’s playing; I have yet to hear him play timidly and don’t think that’s part of his musical makeup. He considers the Beethoven concerto “the greatest of all concertos,” as he wrote in a mass email advertising the concert, and probably the majority of critical opinion would side with him. Like many of Beethoven’s works from this period — the Fourth Piano Concerto, the Fourth Symphony, the Appassionata piano sonata — it had no precedent for its innovative form, emotional and dramatic scope or breadth of motivic development.

Unlike most other concerti for the violin, no matter how terrific on their own terms, a performance of the Beethoven is something of an event, and a sense of occasion always accompanies it. Oliveira gave it everything he had, playing it with a clear sense of reverence throughout, so much so that the first movement was somewhat on the slow side, which made the second sound more like a continuation of the same mood than a break with it.

Oliveira brought to this task big, beautiful tone; confidence and command at each entrance; and a sense of when to turn on the virtuosity in a concerto that despite its enormous difficulties is anything but a flashy star vehicle. In the cadenzas (I think they were Joachim’s), Oliveira had surely practiced these intensely, spilling out the bravura runs in particular with spotless accuracy.

He played the first two movements spaciously and with deep emotion, especially in the second movement, with its elegant commentaries on the short-breathed theme that opens it. In the finale, he dug deeply into the catchy rondo theme; it sounded rustic and ingratiating. Judd kept the orchestra well in the background when Oliveira needed them to be; the conductor is a fine accompanist who pays close attention to his soloist.

The large audience at the Roberts erupted in vociferous cheers at the end of the concert, jumping to its feet and acclaiming the performance, and indeed it was a fine one. It takes nothing away from Sunday’s achievement to note that it would have been ideal for this concert to have been a Florida Philharmonic concert; the majesty of a larger ensemble seems to fit Oliveira perfectly, and while it’s good to see him playing all kinds of smaller situations, one hopes to see him again one day in front of a large ensemble, which seems to be his natural habitat.

The Symphonia Boca Raton closes its season with two concerts, one on Sunday, April 6, at the Roberts Theater, and the other on Tuesday, April 8, at the Eissey Campus Theatre in Palm Beach Gardens. Former Seattle Symphony conductor Gerard Schwarz conducts an all-Mozart program featuring the Posthorn Serenade (No. 9 in D, K. 320), the Clarinet Concerto (in A, K. 622), with soloist Jon Manasse, and the Jupiter Symphony (No. 41 in C, K. 551). Call 866-687-4201 or visit www.thesymphonia.org for more information.