As program-organizing gimmicks go, building one around a number is clever and useful, and for the Palm Beach Symphony, constructing its Sunday night program on “39” ― the group’s current anniversary year ― offered listeners an interesting variety of selections as well as a short course in the development of the Austro-German symphonic tradition.

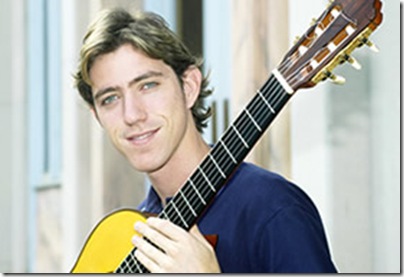

The concert in the Flagler Museum’s train-car gazebo also introduced audiences to a young Argentine-born guitarist, Sebastian Acosta-Fox, who performed what is without any doubt the most popular of all guitar concertos, Joaquin Rodrigo’s Concierto de Aranjuez (written in 1939).

Acosta-Fox proved to be a fine player with nimble fingers and a good sense of the special delicacy of this concerto, and he did made compelling drama out of the cadenza material in the second movement. But he was a little out of tune in the first and second movements, and he was hampered, moreover, by a couple other things: conductor Ramon Tebar’s tempi, and the acoustics of the Flagler gazebo.

The gazebo is a big, high-ceilinged space with a resonant acoustic that adds plushness to the sound of the instruments but has so much echo that it can easily sound muddy. Soloists in the Rodrigo are often miked to help improve the balance, and that certainly would have helped here (unless there was a mic I didn’t see). No matter how effective Acosta-Fox could sound on his own, he ended up swamped by the orchestra when it was going full tilt.

But it was the tempo of the Adagio set by Tebar that was most amiss. He took it a little too fast, and tended to rush the players on top of that, which took away the breathing space this music needs in order to make its fullest impact. Rodrigo’s tune is more a found folk melody than a composed one, but it needs to speak, and it can’t do that if the tempo keeps driving ahead.

The finale was somewhat limp, with a walking-tempo smoothness brought to music that needs a little more movement, plus lightness, shortness of attack and a sense of sparkle. It’s an old-fashioned neoclassical movement, and the contrast between it and the two previous ones should be sharp. Without it, the music was merely pleasant and well-played, rather than engaging.

On the other hand, the concert opened with a lovely performance of the Czech Suite (Op. 39) of Antonín Dvořák. This is also music for which the Flagler acoustic was most complimentary, with woodwinds and brasses clearly standing out to maximum coloristic effect.

The orchestra played this music beautifully, and Tebar led it with a strong sympathetic feeling for the composer’s energy, his folk flavor and the suite’s wide range of mood and style. His opening tempo for the first pages of the Praeludium was adagio rather than allegro, but it worked, and the result was that the Suite started with a very pretty sense of gradual awakening that set the stage well for the movements that came afterward.

The second-movement Polka had just the right sense of Dvořák lilt, with its hurry-up phrases in the strings and buzzing trills in the winds; by contrast, the Sousesdká third movement was more formal, but after its demure opening, Tebar let the orchestra indulge in full-throated playing that was lovely to hear.

Flutist Nadine Asin, English hornist Catherine Weinfeld and hornist Maria Serkin stood out in the fourth-movement Romanze, and the closing Furiant worked up a terrific head of steam in the coda, with a huge swell from timpanist Mark Schubert that made for a showy but effective closing.

The second half of the well-attended concert featured the symphonies by Haydn and Mozart that later scholars have given the number 39. The Mozart symphony (in E-flat, K. 543) is one of the great masterworks of the symphonic literature, but the Haydn (in G minor, Hob. I: 39) is relatively little-known and dates from an earlier period of development in the history of the form.

It’s also a tense, exciting piece rich in Sturm und Drang, with dramatic pauses in the first movement, huge leaps in the violin theme in the finale, a delicate slow movement and a stern, powerful minuet. It’s also a work that suits Tebar’s aggressive, forceful style; his inclination to ride herd on pacing gives early Haydn an extra boost of firepower. It may be anachronistic, but in its departure from the caution that can be heard in historically minded performances, it strikes me as closer in spirit to what the composer had in mind.

And so we had a swift first movement with wide dynamic range and a vivid feeling of power and mystery, while in the Andante, Tebar had the orchestra speak with volume and attention to long melodic line; that and a dramatic crescendo made it more 19th-century than 1768, but it was compelling.

The finale, too, benefited from its breathless, muscular reading, with the strings in particular doing a fine job with their repeated rushes of downward scales. This was a thrilling performance of this symphony, the kind that makes you want to hear many more of the early Haydn symphonies.

The concert ended with the Mozart, and while the orchestra itself played admirably, Tebar’s interpretation was eccentric to say the least, and in a way that was almost perverse rather than refreshing.

The introduction was big and bold, but not carefully thought out as a mini-movement in itself, with a real need for shaping line and making something out of that repeated one-two motif in the winds that suddenly sounds the alarm when it becomes a clashing minor second. The first movement that followed was just a little too fast, almost like a waltz in one beat to the bar. But surely the writing here demands a bit more leisure to make its point and to give the orchestra somewhere to go. And he insisted on closing two or three of the cadences out of tempo, with tenuto hammerblows that were jarring rather than emphatic.

I also found the wonderful slow movement too fast, and while the conductor paid good attention to dynamics, it sounded like he was eager to get past the soft stuff in the first pages and get right to the anguish and stress of the middle section. This is music that is virtually Beethoven, far ahead of its time and a major advance in the form, but there was too much haste, so that the subtleties of the writing — those beautiful, opera-ensemble woodwind passages, for one — were lost.

The third movement, again, was much too fast, particularly in the celebrated clarinet solo in the trio, which has to be allowed the room to make its point, but Tebar’s pedal-to-the-metal approach made it sound like the audio version of a Flickr vacation-photo slideshow set on too rapid a rotation, so as not to weary the family.

The finale was very speedy, but it worked reasonably well, especially with the repeats, and the players did yeoman work in trying to follow their leader’s erratic conception of this sublime masterwork. They did very well considering, though it did leave me wondering how exceptional it might have been with a more careful reading.

Ramon Tebar has many gifts, and it’s exciting to have him leading a good local orchestra, and bringing his youthful and inventive take on things to the podium. But it should be noted that he also is the music director of the Florida Grand Opera, and it seems to me that he treats many of these pieces as he would if were they operatic scores, where sudden changes of mood and style are central to the experience; good theater conductors, indeed, are highly prized for their ability to change things on the fly in reaction to the exigencies of an individual performance.

But one Puccini-sized brush should not tar all, and more musically satisfying concerts can be presented if a greater variety of stylistic attention is paid to the pieces on the program.

The Palm Beach Symphony’s next concert, a chamber-style evening, is set for Monday, Feb. 18, at Bethesda-by-the-Sea Episcopal Church in Palm Beach. Soprano Nadine Sierra will be the soloist for the Erwin Stein chamber orchestra arrangement of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony. Also on the program are Arnold Schoenberg’s arrangements of Johann Strauss II’s Emperor Waltz and Roses from the South, and an arrangement of Debussy’s Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun. 7:30 pm. Tickets: $50. Call 655-7226 or visit www.palmbeachsymphony.org