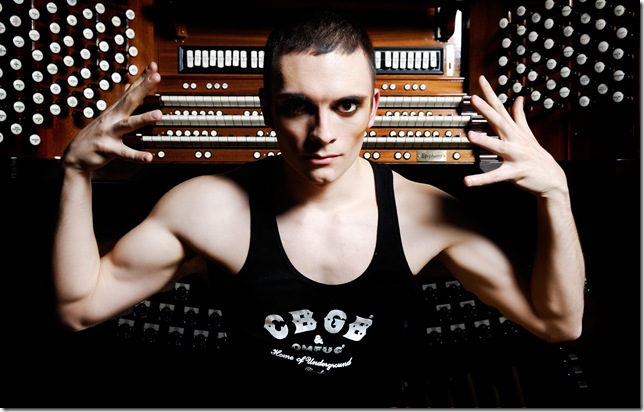

Cameron Carpenter is on a mission to liberate the organ from the confines of the church, and bring this most hidebound of instruments into what he calls an “ecstatic future.”

The brilliant young keyboardist and Peck’s bad boy of the organ world, who performs tonight at the Festival of the Arts Boca, is critical of the way the organ is understood in the world of music today, and he traces that to its long association with religious ceremony.

“The organ is a massively contradictory and paradoxical instrument that has, in addition to many other factors, an extremely long history,” he said by phone from Los Angeles recently. “The instrument is mired in tradition and is also the only instrument that separates the energy output of the human body from the actual generation of what’s happening musically. It’s a degree of removal which I think is very interesting, but which also causes a psychological separation for the player. It’s my position that the organ as it’s been, the pipe organ — which is to say the traditional organ in its traditional role — is an analogue for God himself, or herself, if you choose to believe in such a thing, and of course I don’t.

“If you understand that for hundreds of years … the organ was sort of co-opted to become a handmaiden of religion, then of course it becomes very clear that there’s a big problem with having a human ego attached to that. Which is the fundamental reason that the bulk of pipe organs being built today effectively conceal, or at least hide, the person playing them. They either do it by great distance or by literally absorbing the person into the architecture of the instrument, all of which is wildly inappropriate when we are talking about anything but church music.”

Tonight, Carpenter will be the soloist with the Boca Raton Symphonia at the Festival of the Arts Boca. He’ll perform the Toccata Festiva (Op. 36) of Samuel Barber, the Organ Symphony (No. 3 in C minor, Op. 78) of Camille Saint-Saens, and the Spitfire and Prelude of William Walton. The Symphonia, led by Constantine Kitsopoulos, also will perform Barber’s School for Scandal Overture to open the concert at the Mizner Park Amphitheater.

Carpenter, 32, already has had a remarkable career. He grew up in Meadville, Pa., where he was home-schooled by his parents. His father, a designer of industrial furnaces and an engineer, installed an organ at his factory where his son could practice during production.

“What ended up happening was this situation that I could only appreciate many years later … We had this totally Henry Cowell or John Cage situation because I was practicing while people were cutting metal and running forklifts and doing the loudest possible welding, and listening to Top 40 radio,” he said. “And I was just carrying on with Buxtehude. What a fabulous situation! What a wonderful furnace, literally, what a wonderful kitchen for me to be working in. And what a fabulous eye-opener to later, the idea of working in a church, or trying to practice in this boring church where nothing was happening.

“It just paled in comparison, and of course firmly, as if any greater affirmation of this were needed, totally reminded me that I didn’t want to have to spend my life working in a situation where I would have to be in a church ever, let alone all day,” he said.

Carpenter joined the American Boychoir School at 11 as a boy soprano, then went to high school at the North Carolina School of the Arts, where he began composing and arranging in earnest. One of his efforts, at age 15, was a transcription for organ of the Mahler Fifth Symphony.

“There were things I learned about the piece, but the things that have served me the best were the things I learned about the limits of my own abilities, and the limits of the organ and how I would have to address them,” he said. “Great art teaches us about ourselves.”

He studied at the Juilliard School beginning in 2000, earning a master’s degree in 2006 and going out on tour. His first album, Revolutionary, was released on the Teldec label in 2008 and was nominated for a Grammy award, the first solo organ disc in the history of the Grammys to achieve that honor. His 2010 album and DVD, Cameron Live!, came out in 2010, and the year afterward, he premiered his first organ concerto (The Scandal, Op. 3), with the German Chamber Orchestra on New Year’s Day of 2011.

“One of my goals is to write the three great neo-Romantic concerti for organ and orchestra by the time I’m 40,” he said. “But at heart I’m really a performer, and the composition is to some degree an outgrowth of my need to have the right material, and to have my own stamp on it … I think it’s difficult to say (composition) will be the ultimate direction. I think it will always be a combination of both.”

Now a resident of Berlin, where he’s lived for two years (“I just love the place”), Carpenter has a huge repertoire at his fingers, including the complete organ works of J.S. Bach and Cesar Franck, and has arranged hundreds of other orchestral and piano works for the organ.

For tonight’s concert, he’ll be playing a Rodgers digital organ that’s being supplied for him. Early next year, a new model of digital organ designed to his specifications will be unveiled, though he’s not at liberty to reveal the maker of that instrument. He describes himself as the “world’s leading advocate for the digital organ, even though there’s no competition for that title.

“But it is really an instrument that I believe in so firmly, because for an artist to be at the knife’s edge of an instrument that’s still developing and maturing is an unbelievably rich artistic experience, and has everything to commend it as far as being able to bend the instrument to your will and to push it in lots and lots of new directions in which it’s never gone,” Carpenter said.

And the chief direction is away from the past.

“The thing that’s so important about the digital organ, and so threatening to the tradition of the organ in such a deliciously wonderful way, is that the digital organ literally represents the making, into an ecstatic future form of some kind, the — if you will — soul of the organ, and separating it from all of these endless roomfuls of wood and metal junk. And literally the organ goes from being this incredibly earthbound installed entity that requires massive amounts of electrical power, and it’s sat there for 80 years, and it’s part of the building and it’s not going anywhere – in so many ways – and then turns it into this ball of electrons that can be sent anywhere.

“It gives us the sound of the organ as a kind of hanging garden, a mythical kind of thing that exists there, that we cannot deny our ears, and at the same time we have liberated it from this earthbound structure,” Carpenter said. “There’s a symbology there, I think … It represents the idea that something can literally transcend itself.”

Carpenter also argues that much of the current organ repertoire could use some reexamination.

“One of the unspoken taboos of the organ is to admit that there’s a great deal of organ music that is much, much better for the player, so to speak, than the listener, an accusation I would firmly point at many of the organ works of J.S. Bach, an accusation I don’t think takes away from their status as masterworks,” he said. “Nevertheless, the existence of a work as a masterwork does not in any way mean that it’s automatically also a perceptible pleasure for an average audience.

“Of course, while there are many organ works of Bach that are perfectly enjoyable to the audience, there are many that are sort of exercises in turgidity for the audience, however genius they may be as compositions or brilliant they may be for the organist, who is no doubt swaying and moving the elbows in a fitful expression of their psychological and physical manifestation of what they want people to understand,” he said.

That’s not the case with the Barber Toccata Festiva on tonight’s program, he said.

“That is just exactly the opposite of the Barber, which is one of the wonderful things about it. It’s written in a way that’s highly effective for the orchestra, challenging for them but reasonably written,” he said. “It’s very important to me, when I’m working with an orchestra, that the orchestra has good material to play. And the Barber is going to give us that.”

The Walton, originally written for a World War II film, has been arranged to provide Carpenter with more of a solo role, but in the Saint-Saëns, he’ll be taking more of an ensemble role.

“That work is best left as what it is, which is a fantastic symphony. And the nice thing about it is that it’s an opportunity for me to do something that’s a little bit rare for me, which is to more or less work as an orchestral player,” said Carpenter, who also will be performing some solo works at the concert.

Next month, Carpenter plays three concerts with the Los Angeles Philharmonic and does a solo recital at Disney Hall, plays Luxembourg, Switzerland and Germany in May, and in July collaborates with maverick director Peter Sellars and baritone Eric Owens at the Manchester International Festival in England. Sellars is staging the Suite on Verses of Michelangelo (Op. 145) by Shostakovich, and the cantata Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen (BWV 56) of Bach.

To talk to Carpenter is to talk to a person of ferocious intellect whose zeal in redefining the culture of his instrument is at one with his artistic project; he does not attack the holies of the organ world solely to create discomfort. It is, rather, a pure expression of the kind of art he is creating and seeking.

“It really is the situation for me that those barriers don’t exist, and arguably shouldn’t exist,” he said.

Cameron Carpenter plays with the Boca Raton Symphonia tonight at the Mizner Park Amphitheater, Mizner Park, Boca Raton. The concert begins at 7:30 p.m., and tickets start at $15. Call 866-571-2787 or visit www.festivaloftheartsboca.org.