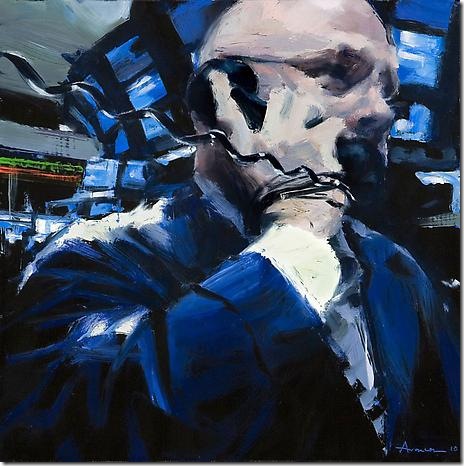

Men in dark suits and ties are seen voraciously tackling the phone, their blurry faces fixed on the screens higher up and on their desks. They wear watches, glasses and sport thinning hair. This used to be the image of a respectable man.

An exhibition of paintings by Ben Aronson, currently running until Feb. 10 at the Ann Norton Scuplture Gardens, may not be the hottest show of recent times nor the most attractive, but the inclusion of in-your-face social realism depicting Wall Street traders makes it very significant, even unique.

How often does the mundane money-making world of stocks and finance appear on canvas?

The Ann Norton Sculpture Gardens had limited space and a modest setup. Aronson lent his famous cityscapes plus a relevant subject matter that does not take a lot of room. His bold, up-close narratives painting the tension, drama and speed of the world of Wall Street are all small-scale pieces with a touch of intimacy.

Defeat is not a possibility in this kind of universe, until it is.

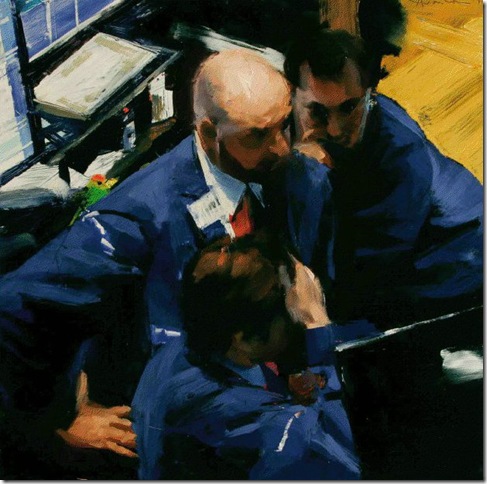

On The Floor (2011) depicts three preoccupied figures staring at a screen. Their gestures and expressions suggest very bad news. One of the men, the youngest one in the group it seems, takes his hand to his forehead. I imagine it sweaty, the veins about to explode as he tries to figure out a solution to the problem. His face is hidden.

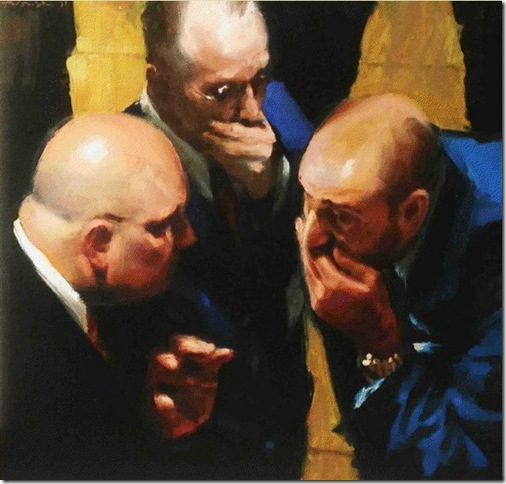

Three Wise Men (2011) zooms in to a conversation perhaps we should not be hearing. Two men cover their mouths in shock as a third sinister one whispers something that must remain a secret. He emerges from the left corner, wearing a black suit. The light focuses on his shiny head bringing out his baldness. But the man does not seem more transparent or any cleaner.

There is a slight satisfaction in seeing these men of power get affected by unplanned events. And do not be surprised if the anxiety captured in these and other pieces, such as The Rumor (2010) and Talking Numbers (2010), jumps out of the frame and you feel the urge to bite your nails. Although for that to happen, you will first have to stare at the scene long enough. Most people walk away.

This is a story still too fresh from a world still too technical and complicated. Besides, nobody wants to see the bad guys in action and winning all over again, not even on canvas.

But this is only the latest theme from an experienced hand born to a talented couple in Boston –Aronson’s father was among the early Boston expressionists and his mother was an accomplished portrait painter. Beginning in 1990 Aronson’s paintings could be found in group and solo shows at galleries and museums across the country, including the Boston Museum of Fine Art, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and the Denver Museum of Contemporary Art. When financial expert Joshua Brown wrote his book Backstage Wall Street, paintings from Aronson’s Wall Street series landed on the cover.

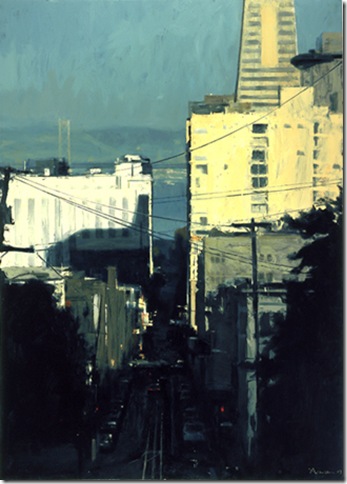

It is still his thick-paint, large-scale cityscapes depicting Paris, San Francisco, Boston and New York that most people recognize. And these, precisely, welcome us as we enter the gallery.

Dark trees on the bottom left and right corners frame the scene in Low Sun, Rising Shadow (2007). A dark road extends before our eyes like a serpent spitting buildings on both sides of the street. The colors are somber and a pronounced shadow rests on the white tall building to the left. Electrical wires go from one side of the canvas to the other, crossing right in front of the blue sky.

A dark tall structure rises before us in Reflected Dawn, Above Madison (2011) but it can easily be avoided. We, the spectators, are like birds flying up high. Inside a shiny skyscraper, lights are already on. The darker spots of the glass structure serve as the perfect mirror to the peachy pink sky. Aronson gives us the best seat of the house. We decide where to look. In the distance, light pinks, purples and oranges form a romantic vision of the city. Down below, it is the traffic and brake lights that bring us back to reality.

These works seem each like an experiment in color and light, but, most importantly, they seem to be playing a game. How abstract can they get before they lose reality? How real before they lose the mystery?

In La Tour d’Argent (2007), old lanterns hang from pale pink walls. With the green light, a figure on a scooter or bike drives away from the viewer toward the brighter, whitewashed background. The machine is captured in motion, as if it were a photograph. There is a faceless figure facing us on the right bottom corner. His hands rest on his jacket pockets as he walks. We almost lose him in the rich dark browns and reds of the local businesses and shops.

The show is not very big and only takes a few minutes to walk.

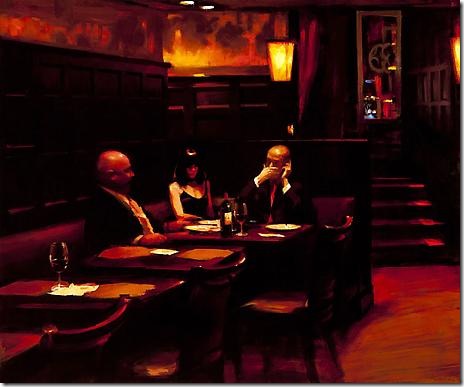

If you go, make sure to view Aronson’s take on Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks series. His moody, dimly-lit scenes convey the same uneasiness and disregard Hopper portrayed in 1942 by painting people who do not really want to be there, interacting with one another or with us.

In one of them, a young brunette wearing a black dress sits between two suits looking miserable. A bottle of red wine rests on the table but only one glass can be seen. The woman is trapped in the corner. One of the men is talking on his cellphone while his chunky friend stares. I feel like saying: where are your manners? But it would not help anything.

Ben Aronson is on display through Feb. 10 at the Ann Norton Sculpture Gardens. Galleries are open from 10 am-4 pm Wednesday through Sunday. Admission: $7. Call 561-832-5328 or visit www.ansg.org.