As we move further past the high-water mark of minimalism, the stature of its major practitioners can be seen more clearly in our rearview.

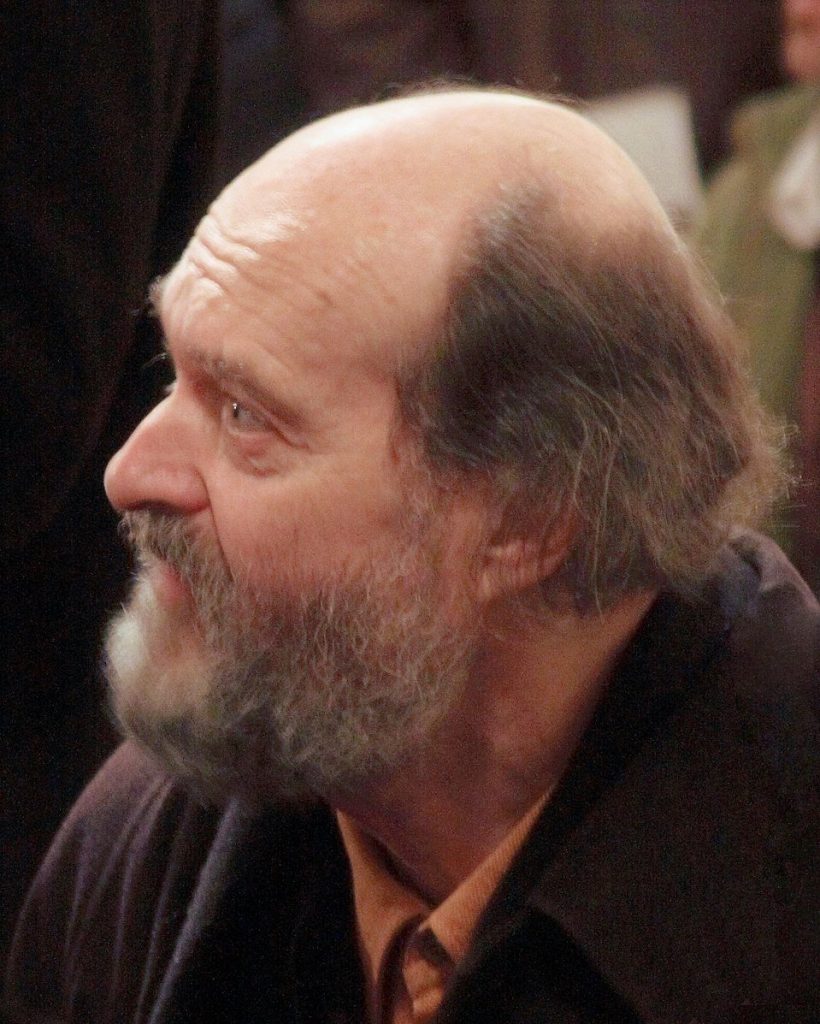

A performance Saturday night of the Passio, a 1982 setting of the Passion according to St. John by the eminent Estonian composer Arvo Pärt, now 82, brought something particular about Pärt’s work into high relief: He is the purest and most intellectually rigorous of the minimalists, far more so than familiar American entertainers such as Philip Glass or Steve Reich. It may be that Pärt’s intense religious faith is the driving reason for that, but his Bachian understanding of how a single change in a small interval can completely change the emotional color of a piece may have the most to do with it.

Pärt’s Passio was presented as the final work in a season of Passions presented by the Miami concert choir Seraphic Fire, and for its performance at All Saints Episcopal Church in Fort Lauderdale, the choir and its founder-director Patrick Dupré Quigley had the services of five instrumentalists and nine young singers from the Ensemble Artist Program at UCLA, where Seraphic Fire singer and associate conductor James Bass is the director of choral studies.

As Quigley, who compared the experience of listening to Passio to “an aural yoga class” noted, the music of this work has much more to do with the 14th century than it does the 19th, and indeed the ghost of a 13th-century composer like Pérotin could even be heard in some of the music. Built around a very small amount of musical material in A minor, and a separate key center in the chorus based on the dominant of E major, the music is separated throughout by varying pauses, so that the silence is as much a part of the story and the musical action as are the notes and chords themselves.

Like most minimalism, the repetition of colors and chordal patterns is, for an audience accustomed to a different kind of listening, immensely frustrating, but here in the Passio, Pärt saves the payoff for the final bars, when a new chord, that of D major, is used for a slightly new pattern in the chorus, and the effect is earth-shattering. The tension built into the music is enormous, and in that way it is perhaps a more perfect reflection, not of an observer at the chaotic and violent scene of the actual Passion, but of the anguish experienced by a man of faith hearing this story while knowing and yet still dreading its outcome.

Such a demanding piece for the listener is even more difficult for the performers, and of them it can only be said that having in South Florida a group that can pull this off, and draw so many people to a church on Saturday night, says encouraging things about the increasing sophistication of the local arts scene. In every respect, from the five instrumentalists — violinist Sonya Chung and cellist Grace An, oboist Max Blair and bassoonist Eddie Burns, and organist Yu Zhang — to soloists Bass (who sang Jesus), tenor Steven Soph (Pilate), plus the four soloists of the Evangelist (soprano Jolle Greenleaf, alto Virginia Warnken, tenor Patrick Muehleise and bass Steven Eddy) and the expanded chorus that sang Peter and the other roles, this was a stellar performance, brilliantly executed and presented with a palpable sense of respect for a profound work of art.

With so much of the music being drawn from such a tiny and shallow well of notes, other factors became more compelling as the ear was being slowly refit for a circumscribed universe. Bass’s Jesus was particularly moving, as the full warmth of his bass voice embraced his slow-moving lines, giving it an otherworldly feel not dissimilar to the Jokanaan of Richard Strauss’s Salome, whose music stands apart from its operatic world. Also especially notable was the singing of Warnken, whose lovely, melancholy alto brought a sense of real sorrow and tenderness to her solo lines.

Quigley, who had to be something of a human metronome as he counted through the work’s many moments of silence, had strict and admirable control of his forces, who made their entrances with exemplary precision. The chorus sang with white-tone forcefulness and little to no warmth, but that was entirely fitting for the austerity and seriousness of the music.

If Arvo Pärt’s aesthetic is not to everyone’s taste, and the Passio too devoid of the pleasure principle to compel listeners any way but through burning spiritual devotion or sheer joy in intellectual exercise, it nevertheless is, as Quigley said, a 20th-century masterwork and a monument of the minimalist style. In exploring this music and carrying it off so ably, Seraphic Fire has honored its composer and his era, and by extension the whole artistic project of the late 20th century.