Chekhov’s rule in theater was this: If you’ve got a gun on stage, you’re going to have to fire it at some point.

By the same token, if you promise people a monster, you’re going to have to show it. But the Palm Beach Opera’s new production of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, which opened Friday night at the Kravis Center, dispenses with the climactic theatrical device of the opera — the arrival of Giovanni’s doom in the person of a giant stone statue — and, frankly, it simply doesn’t work.

Which is a shame, because in almost every other respect, this Don Giovanni, directed by the up-and-coming Italian director Stefano Poda, is otherwise so different and theatrically effective that opera aficionados should want to see it. He has created a kind of netherworld of bleakness and decay, of internal rot, that reflects the moral disarray into which Giovanni has cast his world, and he has made it interesting to look at.

Instead of scenery, we have one giant room with doors, the central one at the back being much taller than the others. A series of hanging tapestries that turn out to be scrims are lowered and lifted as the action progresses, in some cases turning into glowing doorways, and in others serving to provide a film over something like interpretive dance performed by a woman in white (Cecilia Dougherty). Lighting, which Poda designed along with the costumes, is a series of bold colors (blue, orange, deep yellow) that suffuse a scene, or a strip of narrow white that highlights the pages of Giovanni’s famous little black book as it is strewn across the stage.

Poda’s costumes are sumptuous Venetian Carnival, a century later than the original setting of the opera, and for most of the two acts, chorus and supernumeraries walk glacially across the stage in a kind of stately sarabande, with their thick cloaks, masks and tricorn hats creating a constantly shifting backdrop. The action is often frankly sexual in a stylized way, with characters often lying down on the stage in about-to-be-ravished positions, and instead of a table laden with food in the final scene, Giovanni and Leporello “feast” on cloaked women, biting into their arms and necks until they collapse in inert heaps.

It is not in any way a conventional interpretation, but for the most part it is compelling theater and intellectually coherent, and the Palm Beach Opera should get credit for trying something so different.

But it falls flat when it gets to Giovanni’s confrontation with the dead Commendatore, whom Giovanni has slain in the first act and who returns like Hamlet’s father in the form of an avenging monument of stone. Poda’s conviction is that the Commendatore is really Giovanni’s conscience, and so we see no statue in the cemetery move its head and speak, we see no statue arrive for dinner, we see no statue grasp Giovanni’s hand and seal his doom.

Instead, Leporello and Giovanni act out the cemetery scene to the air, facing the audience. And when the Commendatore (Peter Volpe) arrives for dinner, he stands in the aisle, in a tux, while Giovanni, behind a scrim, is slowly approached by a host of figures clothed in the conical hoods of the Spanish Inquisition. Squirming, shirtless men then surround Giovanni and swarm over him, dragging him to perdition in front of a huge backlit cross, which adds a touch of heavy-handed camp.

The idea that Giovanni’s conscience has come back to wrestle with him is an interesting one, but it’s too amorphous to work in concrete theatrical terms. It doesn’t come across, and I guess the only way you could do it would be to show the stone guest coming to dinner, but instead of looking like the Commendatore, he looks like Giovanni himself.

Up until that point, the audience seemed willing to go along with this fascinating take on Mozart’s opera, but Poda lost them in the Commendatore scene. His reception at the curtain call was icy, with applause suddenly dwindling to almost nothing and some muffled booing at the back.

The other effect of Poda’s staging is that it draws a lot more attention to the singing, particularly in Act II, which for much of it is a series of elaborate, static arias for the principal singers.

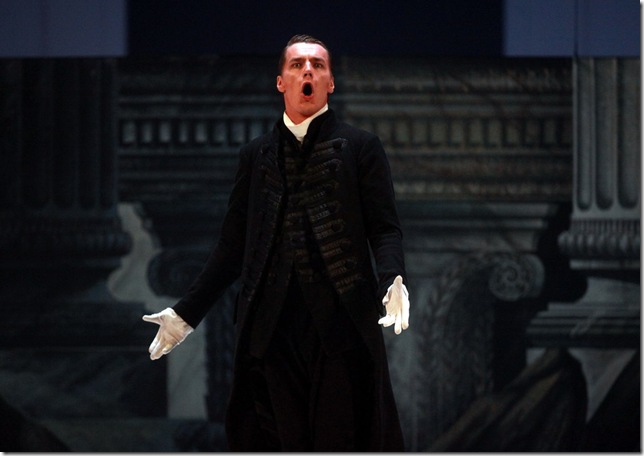

Gezim Myshketa, an Albanian-born baritone, made an excellent Don Giovanni, acting the part with relish but not hamminess. He has a strong, clear voice and he deployed it well throughout the night, most especially in the Act II aria, Deh vieni alla finestra, which he sang with real feeling, using a hushed half-voice when comparing the maid’s sweetness to honey, and stretching the tempo in and out with the tone of the words.

His Leporello, Denis Sedov, also sang and acted well, and made a believable foil to his master. His voice is thicker and deeper than Myshketa’s, and that worked against him in the Catalog Aria of Act I, which could have used a lighter, more comic approach. Vale Rideout was a fine Don Ottavio, making the most of his creamy tenor to offer compelling versions of Dalla sua pace and Il mio tesoro.

Bradley Smoak, a good actor and a singer with an attractive, decent voice, was an engaging, sympathetic Masetto, bringing Ho capito, signor sì to plausible life. And Volpe, as the Commendatore, has a big bronze voice that was quite effective in the closing moments; his first post-death statements as the statue were somewhat marred by microphone reverb offstage, depriving the audience of hearing both his voice clearly and Mozart’s beautiful trombone scoring.

Of the women, both Donna Anna and Donna Elvira were sung by sopranos with large, commanding voices, and both gave strong performances. Poda gives them a lot of running around to do in difficult costumes, and they handled that part of their assignments with aplomb. Armstrong was compelling as the distraught Anna, and in her final aria, Non mi dir, bell’idol mio, her voice demonstrated a quality of real poignancy, a pleading sound that mirrored her character quite well.

Armstrong did suffer from some shrillness here and there, but that was not true of Julianna Di Giacomo as Elvira. Di Giacomo was less persuasive as Elvira than Armstrong was as Anna, but Di Giacomo has a well-rounded, powerful voice that was exciting in Ah, fuggi il traditor and impressive in Mi tradí quell’alma ingrata, with its leaping melodic line carefully controlled and convincingly delivered.

As Zerlina, Amanda Squitieri was excellent, believable as a gullible peasant girl and a master of her own relationship, and good with Smoak and Myshketa. Squitieri has a relatively rich, mature soprano, unlike the lighter voices that are more common for Zerlina, but it worked well, particularly in her fine reading of Batti, batti o bel Masetto.

The chorus work was unfocused, but that’s primarily a function of Poda’s staging. There was no group of contadinas, for instance, in Act I; that was sung by the women while covered in cloaks and hats, and their backs to the audience, and they had to sing at odd angles to each other. Things were a little better at the very end (Tutto a tue culpe), though a little more male heft would have been useful.

Bruno Aprea conducted the proceedings with his usual mastery and hard-driving tension. Some of the tempos early on were slower than expected, and that might also have had to do with the unusual staging, which has an overall air of deliberateness.

All told, this Don Giovanni gets points for its high style and striking visual ideas, a function of its director reimagining it as a philosophical meditation on uncontrolled id. Because of its intellectual consistency, it loses its impact at the end, when its impact should be greatest. If that makes this production a failure, it does not take away from much of the fine singing and acting in it, either, nor should anything be taken away from this company for going out on a limb and trying something so radical, unconventional and unprecedented.

Don Giovanni can be seen tonight at 7:30 at the Kravis Center, with Daniel Okulitch as Giovanni, Alexandra Deshorties as Anna and Michèle Losier as Elvira. Friday’s cast can be seen again at 2 p.m. Sunday, and tonight’s cast can be seen once more at 2 p.m. Monday. Tickets: $23-$175; call 561-833-7888 (PB Opera) or the Kravis Center (832-7469), or visit www.pbopera.org or www.kravis.org.