By Dennis D. Rooney

“Latin Flavors” was the theme of the Palm Beach Chamber Music Festival group’s second program of its 27th season. It opened and closed with wind quintets, one original, the other a transcription.

Belle Epoque en Sud-America, by the Brazilian composer and conductor Júlio Medaglia (b. 1938), is a suite composed for the Berlin Philharmonic Winds Quintet, who recorded it twice. Consisting of a Tango (El Porsche Negro), a “Vals Paulista” (Traumreise nach Attersee), and a Chorinho (Requinta Maluca), the character of the movements suggest Medaglia’s longtime work as a film composer, including the suggestion of ragtime elements in the last of them. The performers (Karen Fuller, flute; Erika Yamada, oboe; Michael Forte, clarinet (both B-flat and E-flat); Stanley Spinola, horn; and Michael Ellert, bassoon, performed with pleasing lightheartedness.

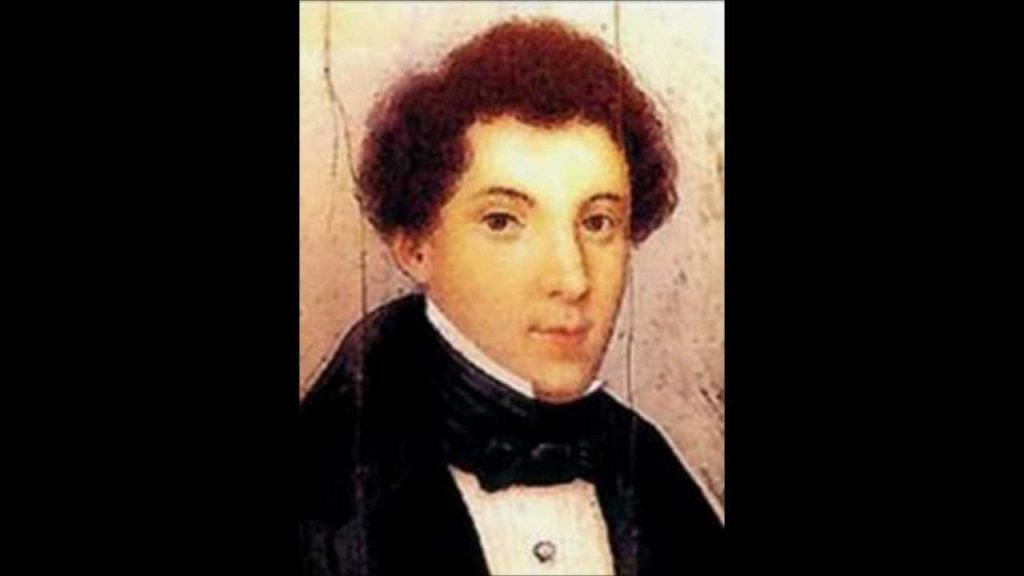

The finest performance of the afternoon was of the String Quartet in D minor by the Spanish-Basque prodigy composer Juan Crisóstomo Arriaga (1806-1826). It is the first of the composer’s three quartets published in 1824. Sent by his father in 1821 to the Paris Conservatory, Arriaga impressed all his teachers: Baillot (violin); Charubini (counterpoint); and Fétis (composition). They were amazed by his ability to use musically sophisticated harmonies, counterpoint, and related techniques, without formal instruction.

Days before his 20th birthday, Arriaga died of what may have been tuberculosis, or as it was often described then, “galloping consumption.” He became known as “The Spanish Mozart” on account of both his prodigy and brief life, and the fact that he shared the elder composer’s birthday, Jan. 27.

One hears the quality of invention that so struck his teachers in the D minor Quartet, where the use of minor tonality is a constant attraction. Throughout its four movements there are echoes of Beethoven’s Op. 18 quartets. Other commentators have also mentioned Rossini, even Berlioz, but Arriaga already speaks with an individual voice in this work, without a suggestion of juvenilia. The performers, Dina Kostic and Michelle Skinner, violins; René Reder, viola; and Susan Bergeron, cello, played a vital account of the score, carefully prepared and highly polished. It was itself as much a pleasure as the reacquaintance with Arriaga’s genius.

Violinist Mei-Mei Luo and pianist Darren Matias were heard in two works. In the first, they were joined by Flamenco dancer Eva Conti (also a horn player who will appear in that capacity on the PMCMF’s third and fourth programs) for Libertango by Astor Piazzolla. Written in 1974, the composer coined the title to suggest his intention to depart from the classical tango in favor of the “tango Nuevo.” With Piazzolla, one either likes it or not (I do not), but the performers played it well.

The second of Luo’s selections was the Fantasy on Themes from Bizet’s ‘Carmen’ (Op. 25), published in 1882 by Pablo de Sarasate (1844-1908), the virtuoso Spanish violinist. Appearing only seven years after the opera’s premiere in 1875, the Fantasy became famous as an encore (by those who could play it) and later became ubiquitous at violin competitions. In addition to being great fun, it is also a catalogue of challenges for the violin, which all the while they are being surmounted (or not, as often happens) must defer to the performer’s ability to characterize the various sections idiomatically. Luo had the most trouble with the artificial harmonics; otherwise, her performance was spirited and colorful but also occasionally breathless.

As mentioned above, the wind quintet returned for a transcription for those forces by Alan Kay of Manuel de Falla’s Three Dances from his ballet of 1919, El sombrero de tres picos (The Three-Cornered Hat), first performed almost exactly 99 years ago at London’s Alhambra Theatre, produced by Diaghilev, with choreography by Massine, and sets and costumes by Picasso. The three dances in this arrangement are from the Second Suite that Falla (1876-1946) fashioned from the complete ballet: a “Neighbors’ Dance” (seguidillas), the “Miller’s Dance” (farruca) and a final Jota.

The players were joined by Conti, who danced all or part of each of the sections. She was attractively gowned in the traditional manner and used heel clicks and castanets as percussion. Perhaps the Crest Theatre’s stage floor would have sounded better with a lighter touch. What was worse was the small sound the instruments made in music conceived for a large and colorful orchestra. The power and sweep of Falla’s melodies was too miniaturized. It may have been fun to play but seemed better suited to the studio than a concert.