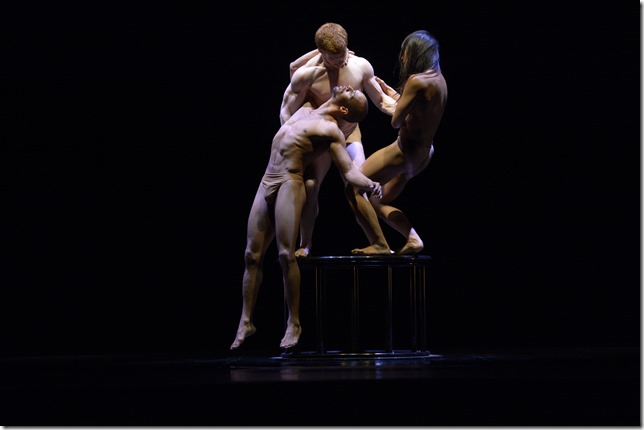

Mike Tyus, Shawn Fitzgerald Ahern and Jordan Kriston in On the Nature of Things. (Photo by Grant Halverson)

They did it again. This oddball dance company has delighted us with another dynamite performance.

Started four decades ago by four gymnasts from Dartmouth College who, after wandering into a dance class, developed an idiosyncratic style of dance (which they named after a fungus that shared the same characteristics), Pilobolus has evolved into something distinctly unique.

On Friday night, closing out the Duncan Theatre’s Dance Series, Pilobolus showed us some of their most recent artistic forays, together with works from their illustrious and inventive past.

Whether it was the mesmerizing slow control and the beauty of the seemingly passive shapes in On the Nature of Things (2014) or the risk-taking, raw and explosive energy in Thresh/Hold (2015), they had us at hello.

How do they do it? How have they managed, year after year, to entertain and amaze audiences the world over with their endless rich innovation? For 40 years, they have continuously excelled in expanding what dance is and therefore have changed the direction of the art form.

Despite numerous generations of dancers in the company, the collaborative work that the Pilobolus dancers have created has always seemed unpretentiously artistic. Working collectively as an artistic family with past and present company members, they form a creative think tank. It is required that they all live in the small Connecticut town that has been the home of Pilobolus for many years.

Rehearsing in a barn with no mirrors (a dancers’ typical evaluating tool), they endlessly experiment —working from the inside out — hoping to break rules and push the limits and boundaries in dance. There they hope, as one of the dancers said in the post-performance talk-back, to create moments, not just steps.

On Friday night at the Duncan, the audience entered the theater to an open curtain that revealed the six company dancers warming up on stage in sweat-clothes. Immediately in this casual setting, a kind of intimacy was established between the audience and the dancers as they encroached on each others’ space.

In order to create transitions between the dances (so that the dancers could change costumes and sets/props could be struck), the program was linked together with a random variety of film clips. A time-lapse film and three amusing cartoons were projected on a screen that rolled down into the viewing space, keeping us occupied like children in the back seat of a mini-van watching a movie — and it worked. We didn’t fidget during the change-overs.

On the Nature of Things (2014), which was performed in ultra-slow motion and in partial nudity, had an engrossing quality to it that was like holding a jar up to the light and slowly turning it to examine the specimens floating in formaldehyde.

It began with one man carrying another man, entering and depositing him on a small, raised platform. With their dark and light limbs entwined, they counterbalanced and lifted each other (or themselves) like masters of capoeira (the Brazilian martial art). It was a power struggle of physical power. The man now returned with a woman, whom he placed standing on the other man’s chest as he revolved him like a sundial. A hint of desire seeped in as the man and woman danced and the other man watched. God creating Adam and Eve?

The trio then merged together and defied gravity with their extraordinary cantilever lifts that floated upward and outward. Observing the relaxed poses and soft feet suspended surreally as the counterweight hung precariously over the opposite edge of the small platform was totally mesmerizing. On the Nature of Things was sensationally performed by Mike Tyus, Shawn Fitzgerald Ahern and Jordan Kriston.

It was so deftly done that I was reminded of the awe I felt standing in front of The Rape of the Sabine Women, the iconic sculpture of the 16th-century Italo-Flemish sculptor Giambologna. The towering marble sculpture of two men and a woman intertwined, one on top of another, equally impressed me with the emotional story that was captured in a moment and with the sheer technical feat of carving the piece out of a single block of marble.

Award-winning Venezuelan choreographer Javier De Frutos was added to the collaborative mix for the creative process of Thresh/Hold (2015) and the result was high-voltage. Kriston was the lone woman sitting on a front doorstep in reflective pose. There was no house — just a door and its threshold. The door opened and a man (Ahern) was expelled out briefly only to be sucked back in as if by some supernatural force.

With a renegade military look, three men dressed in Mad Max-type garb and combat boots acted as manipulators opening and closing the door as they rotated it. The dancers increased their speed and volatility until there was a recklessness to the action. The door was repeatedly wrenched open and closed as the five dancers fearlessly darted through the now madly spinning threshold in order to escape or enter a new place that was accentuated by tight lighting cues that boldly changed from platinum to gold and then finally to red.

The ferociousness of some of moments with its unleashed energy — colliding and spinning — seemed like the rages of the racing mind when one is emotionally distraught. There were moments where Kriston and Ahern were speeding out of control — perhaps reliving those critical peaks in their relationship — only to be caught in mid-air and for everything to stop momentarily. Was it a realization that the unchangeable past is always with us no matter what threshold we cross?

Sweet Purgatory (1991), set to Dmitri Shostakovich’s Chamber Symphony (arranged from his Eighth String Quartet by Rudolf Barshai) was the danciest work in the most traditional sense of the word. The Russian composer wrote the highly personal score in three days in 1960 as an epitaph to himself after being forced to join the Communist Party and finding out that he had a debilitating muscular disease.

The physical movement for the six dancers (three couples) was constructed to weave in and out of the very dramatic music. However, the collaboratively choreographed work rarely just reinforced the score. Instead it stretched, challenged and even defied it. The movement was unusual and it was paired in unexpected ways to the drama of the music.

The many lifts where the dancers surrendered to the flow of the movement with loose lines and hanging feet were perhaps not attractive in the traditional dance sense but they were so very effective. In one that repeated several times, the dancer was grabbed from their buttocks and dragged backward — feet trailing on the floor like a skater going backwards.

During a dramatic musical crescendo, the dancers created a long pause by resting on the floor in fourth position and then suddenly (I am still not sure how they physically did it), they popped up from the floor without any preparation, like crickets.

The program also contained Walklyndon (1971), a brief visit to the light humor of the 1970s, and Wednesday Morning, 11:45 (2015), a sample of the works created with a shadow box. Pilobolus’s incredibly successful Shadowland series of works has been on the Oscars, Broadway, the Olympic games, television and in advertisements.

At the end of the performance, the dancers returned, pulling on their sweat-clothes, in order to talk with the audience. There was a real interactive and intellectual — an almost collegiate — feel to having shared the evening with this artistic family. After astonishing us with what the human body is capable of accomplishing and impacting us with their endless creativity, I left the theatre feeling very stimulated. After all, isn’t that the purpose of art?