I hate that perennial disclaimer, “It’s not for everyone.” Because after all, few great works of art really are. To criticize an artwork solely because it doesn’t satisfy some litmus test of all-encompassing accessibility is fallacious.

A lot of people – a number surpassing its admirers – won’t be able to sit through Wim Wenders’ Pina, a 3D movie for patient grown-ups about the philosophies and creative output of the late modern-dance choreographer Pina Bausch. It’s their loss; the film is a masterpiece of a greater proportion than its niche subject, one of the cinema’s most sensitive and audacious tributes to the pains and triumphs of the artistic process.

It speaks most overtly to why we dance, but it inherently addresses why we make movies and why we go to the movies, why we make art and why we entertain: To move and be moved in ways we haven’t before.

Wenders first met Bausch in 1985, and this project had been percolating for decades. He nearly punted it when the choreographer died suddenly from cancer in 2009; convinced to soldier on with his documentary anyway, he took the film in a genius new direction: He removed the dancers from their familiar confines onstage, filming them performing Bausch numbers in public parks, pools and intersections, excavated buildings, even at the top of a cliff.

In addition to being cinematically ravishing, these sequences create beautiful incongruence between the bodies and their milieus, offering a physical manifestation for the transcendence of Bausch’s work. Everything about Pina, from the three-dimensional immersion of Helene Louvart’s photography to the untraditional series of interviews – quotes from the unidentified dancers play on the soundtrack over portraits of themselves posing for the camera – is a rebuke to the staid formula of the artist biography.

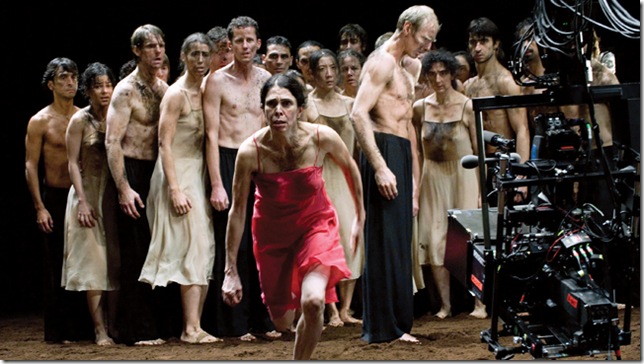

This is only appropriate for a choreographer whose self-reflexive, ritualistic ruminations on loneliness – tempered by humor – defied the conventions of even most modern dance. It borrows liberally from so many disparate art forms that it could almost be considered anti-dance. Her overpowering sets are veritable golf courses of obstructionism, rife with natural elements like sand, rocks and water. Performance art, animation, theater and cinema create a surrealist patchwork of influence, with Bausch’s work conjuring Bertolt Brecht and Looney Tunes, Eugene Ionesco and Buster Keaton.

For Wenders, Pina arrives after more than a decade of sluggish narrative meanderings, and it represents a brash reminder of the German New Wave trailblazer he once was (some of his best lesser-known works, such as Room 666 and Tokyo-Ga, have been in the nonfiction realm).

This time, he’s as focused as a laser beam, clearly enraptured by the art-making process he’s documenting: All the world’s a stage, and stages are all worlds to be explored with curiosity and care. The fourth wall is shattered from the get-go, but so are the other three. Ultimately, there is a place for everyone in the sublime landscape of Pina, if you’re open-minded enough to embrace it.

PINA. Director: Wim Wenders; Distributor: IFC Films; Opens: Today at Regal Shadowood 16, Regal Delray 18, Regal South Beach 18 and the Coral Gables Art Cinema.