By Robert Croan

There was a sense of intended internationalism and ecumenism about the Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra’s Feb. 25 performance on the Broward Center Classical Series.

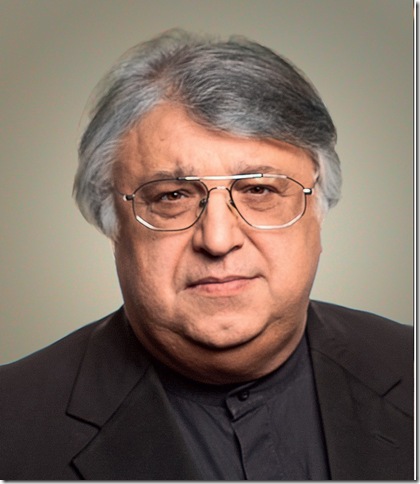

At the start, the orchestra, conducted by Russian-born, American-trained Dmitry Yablonsky, played The Star-Spangled Banner followed by the Israeli national anthem, Hatikvah. The repertory was all-Russian, and the soloist for the evening was pianist Farhad Badalbeyli, who comes from Azerbaijan, a country with a sizable Shia Islamic population that was formerly one of the Soviet Socialist Republics.

For good measure, the pianist offered a piece by an Azerbaijani composer as an encore after his concerto. The orchestra players, of course, were predominantly Jewish. It was certainly an interesting cultural mix.

Most important of all, the Jerusalem Symphony is a world-class orchestra, though its playing on this occasion showed some signs of fatigue from its current whirlwind Florida tour schedule. Yablonsky is not the orchestra’s regular music director — that would be Frederic Chaslin — but the present maestro seemed to have an easy rapport and familiarity with ensemble and the repertory at hand.

The concert took a while to get going. Following the two national anthems, the orchestra warmed up on two bits of pleasant but inconsequential concert trivia: Glinka’s overture to the opera, Ruslan and Ludmila, and the “Polonaise” from Tchaikovsky’s opera Eugene Onegin. The Ruslan overture is actually a delightful morsel, but at that early point in the evening, there was a lot of ragged playing, not perfectly in tune, and a dearth of the work’s inherent sparkle. Tchaikovsky’s Polonaise improved in precision, but lacked somewhat in rhythmic impulsion.

With the anthems and the warmups, it took about half an hour before the orchestra got to the substance of its program. The two featured compositions had their world premieres in St. Petersburg within four years of each other — Rachmaninov’s Symphony No. 2 in 1908, Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in 1912 — but they could hardly be more different from each other. Rachmaninov’s symphony was old-fashioned even for its time: a nostalgic recreation of the sounds and sentiments of the Tchaikovsky era. The younger Prokofiev’s first concerto was brash, energetic and forward looking in every way, searching out new ways to exploit the solo instrument and in the process, show off his own virtuosity as an instrumentalist as well as a composer.

Central to the Jerusalem Orchestra’s program, Prokofiev’s terse concerto is a tense and volatile powerhouse, packed into approximately 17 minutes that simultaneously attack and caress the ear. It’s hard for the listener’s attention to lapse for even a moment of the wonderful work. The young composer took a lot of heat from the established authorities for his daring originality, but the real heat is in the score itself, and that came through in Thursday’s blazing, robust rendition.

Badalbeyli has the fingers to encompass Prokofiev’s wide-ranging chords, the tone clusters and the percussive melodicism, as well as the ability to soften when required for the work’s occasional interludes of lyricism. The orchestra, following the conductor’s solid beat, rendered its part with relish and gusto.

In the old days (when I was at university), Rachmaninov was evaluated as having been one of the world’s great pianists in his time, but a second-rate composer, whose keyboard music was superbly crafted for the instrument but lacking in originality and invention. The exception, arguably his masterpiece, is the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, but his three symphonies were thought of as overwritten, rashly sentimental, derivative, too long for the quality of their musical ideas and the way they were developed.

For this reason, as acknowledged in Jerusalem’s program notes, the score of his Second Symphony used to be routinely cut to maintain a forward sweep in performance. Rachmaninov has come back into fashion, and the traditional cuts are now reopened, bringing the symphony’s duration up to something like an hour. Listeners particularly respond to the lush melody of its third movement, which might have been a prototype for second-rate Hollywood movie scores of the mid-20th century.

The Jerusalem’s earthbound performance failed to justify the greater length. Yablonsky, the scion of a distinguished family of Russian musicians, is a competent, workmanlike conductor but not an inspired one. He has a good baton technique, which worked well other than for some ragged moments among the strings. Brasses were effective in the opening movement, woodwinds provided ingratiating solos as the music allowed, while the principal French horn did yeoman’s work in the melodious Adagio and elsewhere. Some of the work’s final moments were a bit of a scramble, but the audience seemed nonetheless duly roused by the time it was over.