Red Flower (1919), by Georgia O’Keeffe.

By April Klimley

The Norton’s exhibition of Four Women Modernists in New York is full of surprises. Of course, many people will visit it to see Georgia O’Keeffe’s work, especially her Jack-in-the-Pulpit series.

But you are in for an additional treat at the exhibition when you examine the work of three other New York women modernists from the same era, also part of this show, which runs through May 15.

The three other artists are Fauvist/Cubist Marguerite Zorach, modernist Helen Torr, and expressionist/ surrealist Florine Stettheimer. All three lived in New York City at the same time as O’Keeffe, socialized with her or knew of her, and were active members of the modernist movement (ca.1910 to 1930). But unlike O’Keeffe, their reputations faded soon after their death, to some degree because their art was considered “feminine.”

“The majority of critics in their era saw their work through the lens of their gender, limiting their understanding of it,” writes Ellen Roberts in the exhibition catalogue. Roberts, the Norton’s Harold and Anne Berkley Smith Curator of American Art, organized this exhibit.

“But all these artists wanted to be judged as artists,” she explains. Nonetheless, she believes that these artists are still evaluated to some extent through the prism of early critics — by their gender. Roberts is determined to change that.

So as you walk through the exhibition, look at the work of each artist for what it says to you in terms of technique, expression, subject matter and power. Do not be influenced just by the fact at each one is female.

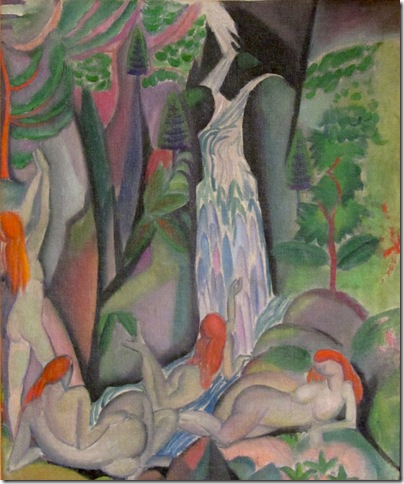

Bathers (c. 1913-1914), by Marguerite Thompson Zorach.

The work of Marguerite Zorach, born in California, comes first — perhaps because her art received relatively objective reviews in her youth upon her return from Paris to California. Critics were shocked by the wildness of her work (part of the Fauvist style), but did not focus on how it related to gender.

This intensity of emotion — a hallmark of Fauvism — is visible in virtually all Zorach’s early paintings. The four stylized women in Bathers, painted in a blocky, flat style, joyously lounge around at the bottom of a stylized waterfall, almost blend into the rocks. Zorach uses the same flat technique with almost no perspective in two other paintings which reveal her love of nature — Deer in the Forest and Sunrise and Moonset, an almost cubist landscape.

Unfortunately Zorach’s powerful, Fauvist oil painting came to a screeching halt with the birth of her children. After that, she turned to the creation of embroidery and textiles because of the time constraints of raising a family. Critics thought of this work as more “feminine.” It certainly lacked the strength of her earlier paintings, although it sold well and helped support her family.

Evening Sounds (c. 1925-1930), by Helen Torr.

Turning the corner, you’ll come face to face with the somber work of Helen Torr. Born in a suburb of Philadelphia, Torr lived with and married artist Arthur Dove. Most of her artwork consists of lonely landscapes, studies of nature, or paintings of buildings. Many critics saw Torr’s work as unoriginal and simply paralleling her husband’s art. Yet her paintings have a depth and tranquility all their own.

For instance, the graceful swirls in Torr’s gouache and charcoal Sea Shell (1928) are mesmerizing, and her Corrugated Building, White Cloud (Light House), and January are beautifully composed and tranquil. Some critics have actually suggested that her charcoal drawings on paper, such as Geometric, were precursors to radical abstraction. No one called her work “feminine,” yet she was held back by her domestic circumstances and lack of self-confidence. Her work remained largely underappreciated until after her death — much of it locked away in an attic at that time.

Turning the corner, you will be captivated by the brilliance and joy of Florine Stettheimer’s work. Instead of solid flat blocks of primary colors, you will see delicate lines and pastels. Instead of dark greens and blacks, you’ll see pale blues, pinks and yellows. Stettheimer’s Self Portrait with Palette (Painter and Faun) is a Fauvist tribute to the joy of art. The faun in the picture might have stepped out of the Nijinsky ballet The Afternoon of a Faun, which Stettheimer saw in Paris.

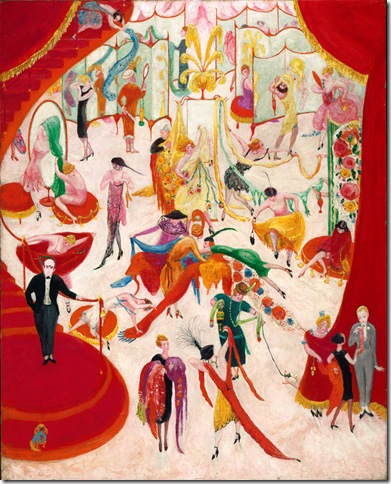

Spring Sale at Bendel’s (1921), by Florine Stettheimer.

This artist, born in Rochester, N.Y., was a decade older than the others in the exhibition. Her early art shows the influence of Fauvism. But after a one-woman exhibition at the Knoedler gallery, which was not a financial success, Stettheimer turned in another direction and never allowed her art to be shown or sold again.

She created a unique surrealistic style in many of her latter works such as Asbury Park South, Spring Sale at Bendel’s, and Portrait of Myself. In these, flattened figures seemed to float across the canvas. Each painting contained a witty commentary on the society she lived in. The dream-like feeling of these paintings resembles some of the work of Marc Chagall. Critics labeled most of her work “feminine,” including the sets and costumes she designed for Virgil Thomson and Gertrude Stein’s opera Four Saints in Three Acts, which received considerable acclaim. Yet after her death, Stettheimer’s work fell into obscurity.

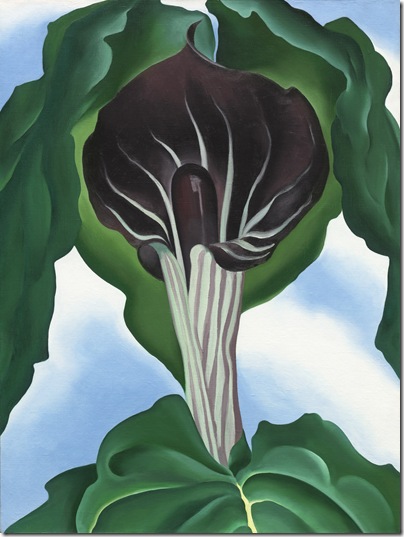

Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. 3 (1930), by Georgia O’Keeffe.

Finally, in the fourth room, you will come to the powerful work of Georgia O’Keeffe. The vivid purple and green colors of her Jack-in-the-Pulpit series stand out starkly against the dark walls of the gallery. But as dramatic as these paintings are, they still reinforce the stereotype which O’Keeffe, too, had to fight against: That gender was at the heart of her art. As one art critic, Paul Rosenfeld, put it, “It is female, this art…”

That certainly can’t be said of her two skyscraper paintings on the far wall, however. The originality of the placement of the low-lying moon in City Night and the exploding light in The Shelton with Sunspots, NY could never be stereotyped as “feminine.” It was this type of work that eventually turned O’Keeffe’s reputation around and began to position her as one of America’s greatest artists. Soon after painting these, although married to Alfred Stieglitz, she began traveling to Arizona to paint. In that way, she continued to grow and flourish as an artist. Somehow, she overcame the domestic and social pressures that limited Zorach, Torr, and even Stettheimer.

Where does that leave the other three modernists in the show? Although talented and influential, none of them was able to completely actualize her talent. Each one was blocked by powerful forces — financial and family pressures, stereotyping by critics, limited opportunities to exhibit their work, and few (if any) sales. All this undermined the confidence of all three.

So another title for this exhibition might be “Unfulfilled Expectations,” if it were not for the fact that one of this circle — O’Keeffe — overcame these forces and did not let them stand In the way of making the most of her artistic aspirations and talent.

Four Women Modernists in New York runs through May 15 at the Norton Museum of Art in West Pam Beach. The museum is open Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday and Saturday from 10 to 5 p.m., and from 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. Thursdays. Admission: $12 for adults, $5 for students with ID, free for members and children under the age of 12. Palm Beach County residents receive free admission every Saturday with proof of residency. Call 832-5196 or visit www.norton.org for more information.