By Lucy Lazarony

When Boca Raton resident Raheleh T. Filsoofi returned to her homeland of Iran last summer, she went determined to see her country through the eyes of an artist.

And she did just that, shooting more than 6,000 photos and videos, seeking out, interviewing, and living with talented ceramic artists and women potters living in villages in western and northern Iran.

For Filsoofi, it was a transformational experience.

“I can really divide my work before and after that trip,” says Filsoofi, 37, who worked as a commercial ceramic artist in Tehran and Miami before joining the master of fine arts visual arts program at Florida Atlantic University. “I think I see things differently.

“I went not as a tourist, not as Iranian. … I went just to see the place as an artist. And I saw things as an artist. And that’s why when I came back everything changed,” she says.

For Filsoofi, “being an artist is to savor the mystery of each moment from past to present in its infinite depth.” And she continues to savor the wonders of her trip: the images, the moments, the memories, the people she met.

“When we change our place and when we go back, it’s not the same,” says Filsoofi, who had been away from Iran for 10 years before returning with her husband last summer. “You see things you couldn’t see when you were there.”

In Tehran, she focused on capturing the long, flowing vibrant clothing of everyday Iranian women.

“Women are so creative,” says Filsoofi, who grew up in Tehran.

She ended up shooting a lot of photos from the back because so many women in the city weren’t comfortable being photographed from the front.

In one photo, she captures a group of women who are gathered together and taking their own pictures. Even from the back, the joy of the moment is clear.

“I loved the way they were giggling and laughing, and I didn’t want to interrupt their moment of friendship,” she says.

Out in the country, Iranian women were more open to being photographed.

“In the country, from far away, I would shout, ‘Can I take your picture?’ and they would say, ‘Yes! Take a picture!’ Filsoofi remembers.

One group of ladies even began dancing for her.

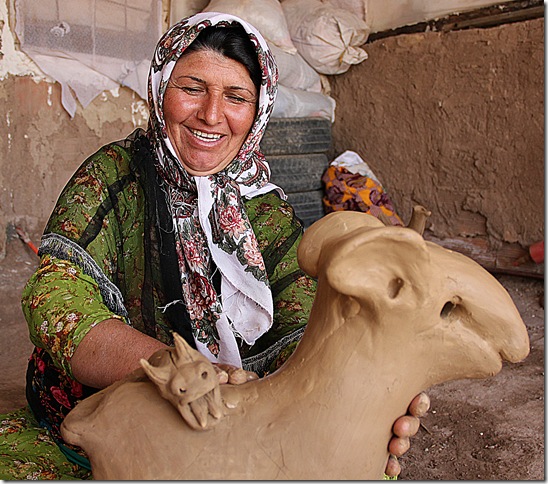

And the three female potters who Filsoofi interviewed during her trip were happy to be photographed.

“Women who create, they are more open,” Filsoofi says. “They wanted to be photographed.”

They opened their homes and their hearts to her, as well, treating Filsoofi and her husband as “queen and king” during their visits to their homes and villages.

But they had a hard time believing that Filsoofi was a ceramic artist and could make pots like they did.

“They didn’t believe that a ceramic artist would just walk around with a camera,” Filsoofi says. “I’m a modern woman who lives in America. Why would I want to make pots?”

But Filsoofi sees a clear connection between clay and photography.

“Clay was an old way of documenting life 5,000, 6,000 years ago. Writing started from clay,” Filsoofi says. “It sort of became a recording medium. Photography is the new way of documenting.”

And she learned much documenting the lives of the three potters in Iran.

One woman works only with her hands, sculpting in clay images from her dreams; another created enough pots to send her three children to the best universities in Iran. A third woman works from 6 in the morning to 10 or 11 at night, making pots with a pottery wheel and working in the rice fields. Her successful businesses employ several people in her village. Her age? 62.

“They’re doing it all,” Filsoofi says. “They do their work. They check the fields. They feed their animals.”

Filsoofi spoke in detail about her experience in Three Women Potters in Iran: Issues of Art, Craft and Gender, an hourlong lecture at FAU earlier this year. Filsoofi says she would welcome the opportunity to give the lecture in other venues.

As for her own work with clay, she knows she will return to it.

“I miss clay badly,” she says. “Clay became like my country for me. It became like my country and I had to get out of it in order to have a new perspective. I was tired of working with clay because I was making very big pieces and it was exhausting.”

Since her trip, Filsoofi has been creating mixed-media installation pieces.

“After coming back from my trip, I felt compelled to work on something that reflects my love and passion for my homeland deeply,” Filsoofi says. “I really wanted to engage the viewer in an intimate dialogue about my culture and to address the memories that I had collected on my journey.”

For Continuum, an autumn exhibition at the gallery of the Cultural Council of Palm Beach County in Lake Worth, Filsoofi created a dress that gathered strips of cloth, images and writing from her trip.

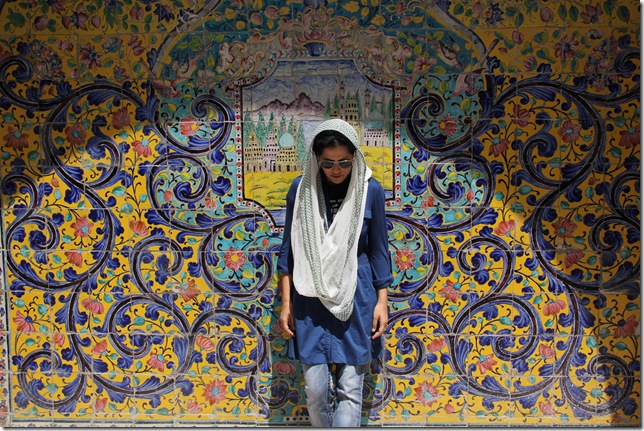

She placed the dress on a mannequin so that it might be viewed from behind, as if it was the dress of one of the women she photographed during her trip. Nearby was a photograph of a very modern-looking Filsoofi, clad in Ray-Ban sunglasses and blue jeans standing in front of a tiled wall at Golestan Palace, one of the oldest historic monuments in Tehran. Her eyes gaze down.

“I was overwhelmed. It’s a beautiful place, a magnificent place,” says Filsoofi, who creates tiles and murals, sculptures and pots. “I also feel the burden of it on my shoulders somehow. I carry it with me. I embrace it. I love it. But it’s just so hard.

“You’re not free from your past,” she continues. “You carry it with you wherever you are.”

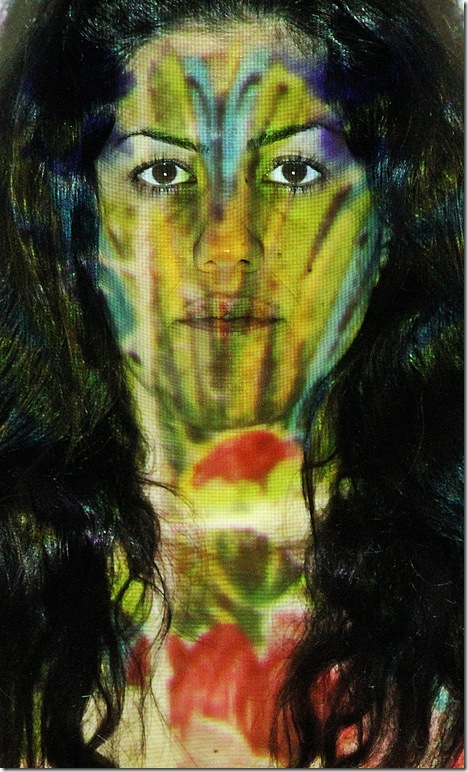

For her latest work, she is projecting images of traditional Iranian artwork onto a wall and then stepping in front of the images, capturing her face and her form as a woman, and transforming the slides into new pieces of art.

“I become part of my past,” Filsoofi says. “I am emerging out.”