“The art of making art” is a frequent fascination of playwrights, who find in the visual arts a metaphor for their own struggle of creation. Currently, by a fluke of scheduling, two such plays on the creative process are on view — John Logan’s 2010 Tony Award-winning Red and Lee Hall’s The Pitmen Painters, from the following season on Broadway.

Both are well-produced and -performed, but there is a definite qualitative difference in the writing. The far more compelling piece of theater is Red, which explains in part why it will be receiving numerous productions at not-for-profit companies across the nation this season. Of course, the fact that it is a two-character, one-set drama doesn’t hurt.

Logan, popularly known for his screenplays for such violent epics as Gladiator and The Last Samurai, takes us into the Bowery studio of abstract expressionist painter Mark Rothko, circa late 1950s. He has a generally bitter outlook on the world and unbridled jealousy toward the newly emerging generation of artists, yet he has recently received a major commission to create four huge murals for the new Four Seasons restaurant in New York’s Seagram’s Building.

Red is both the dominant color of those murals and the hue of anger, Rothko’s frequent emotional state. Rather than a conventional biography of the man, however, Logan concentrates on the relationship between the artist and a fictional assistant and artist wannabe, a young man named simply Ken.

Although deeply self-absorbed, Rothko deigns to impart his philosophy of art to his captive subject. He specifically denies any interest in being Ken’s teacher, mentor, father figure or shrink, though he takes on all of those roles as — over the course of a few years — he goads the boy into questioning authority and thinking for himself.

Naturally, Ken is a stand-in for the audience, as we too have our visual skills honed — “What do you see?” is an oft-repeated inquiry — and we eavesdrop on torrents of hyper-articulate conversation, full of nuggets of wisdom about the nature of art, and specifically art versus commerce. For as he works, Rothko is having grave doubts about the pact with the devil he has entered into, creating art for the walls of a temple to capitalism, where only uncomprehending business executives will ever see them.

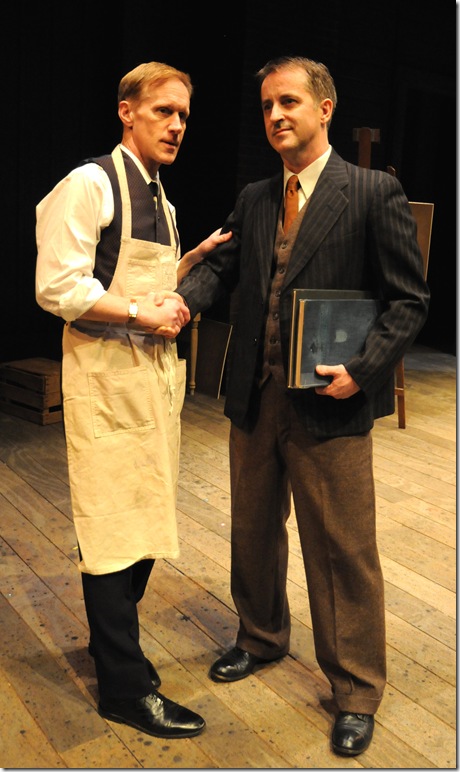

With such emotional turmoil, Rothko is a terrific acting assignment and, at the Maltz, Mark Zeisler does it justice, conveying the hot-tempered and bullheaded man, while suggesting the artistic soul beneath the surface. Ken is the more enigmatic, understated part, but he is crucial to the duet that is the evening. JD Taylor impresses, ably making the transition from empty vessel to his own man, as he attacks back, biting the hand of his master.

Red is a major departure from the Maltz’s usual menu of mainstream musicals, but it is another milestone in it becoming a major regional theater.

RED, Maltz Jupiter Theatre, 1001 E. Indiantown Road, Jupiter. Through Sunday. Tickets: $44-$62. Call: (561) 575-2223.

* * *

Lee Hall’s play The Pitmen Painters is also based in real life, being the tale of a group of coal miners from Northern England who rose to prominence in the art world in the 1930s.

But perhaps because it was too busy being factual, the play never manages to muster much drama. The evening is intriguing — there is surely a play in these miners’ story — but this play is frustratingly inert.

It is a tale that strains credibility, though it is certainly true. A couple of dozen grown men — boiled down here to just five — who have been unschooled since the age of 11, when they began working the coal mines of Ashington, enroll in an art appreciation course to better themselves.

But they had never been to a museum, never even seen a painting. So with no basis in art, the urban teacher who arrives in their midst is frustrated for a way to begin. Eventually, he hatches a plan to gives his eager, but clueless students brushes, paint and canvases so they can learn by doing.

His experiment unleashes their previously unknown artistic talent, turning the miners into The Ashington Group, working-class painters whose primitive art has become acclaimed and collected.

The play also conjures up questions of the nature of art, specifically what is artistic talent, where does it come from and who can claim the title of artist. What it does not have is much tension or theatricality.

The closest it comes to plot is when the miners’ work attracts the attention of wealthy art patron Helen Sutherland. She particularly takes a fancy to miner Oliver Kilbourn, the most talented of the group, who also has an intuitive understanding of conceptual art. To encourage him, she offers Oliver a weekly stipend to paint full-time and he then has to decide whether to give up risking his life down the mines.

Palm Beach Dramaworks certainly gathers a terrific company of actors for the play’s area premiere, but even they cannot hide the fact that their characters are rarely more than two-dimensional mouthpieces for the author’s arguments.

Oliver, played with understated sensitivity by Declan Mooney, is the only pitman who approaches a fully believable character. Colin McPhillamy as dense Jimmy Floyd gets some choice comic one-liners, but that’s really all we know about him. The rest of the miners are fine up to a point, but they have so few opportunities to distinguish themselves.

John Leonard Thompson (instructor Robert Lyon) is nicely unnerved by his students’ lack of knowledge, but he develops a palpable affection for them. And Kim Cozort adds a touch of class as art collector Sutherland, as well as showing off Erin Amico’s well-heeled costumes.

Director J. Barry Lewis stages the play simply and effectively, but it is hard to shake the feeling that there is a better play to be written about these pitmen artists from Ashington.

THE PITMEN PAINTERS, Palm Beach Dramaworks at the Don & Ann Brown Theatre, 201 Clematis St., West Palm Beach. Through Sunday, March 18. Tickets: $55. Call: (561) 514-4042.